“STILL BEDDED,” I said to my buddy Frank Schultz while I eyed the band of Dall sheep rams we were after. I turned out of the wind and scooted back between the rocks that cradled a grassy spot atop the jagged ridgeline. We were pinned down, unable to stalk closer, but at least we were out of the wind.

Schultz had drawn a coveted tag for the Delta area in central Alaska, and I’d come along to help him out.

Now there was nothing to do but wait. I was kicking around anxiously in the pea gravel at my feet when I noticed a hint of dirty metal. A single spent rifle casing lay among the rocks. It had a patina that only decades atop an Alaskan ridgeline can give a piece of brass. As anyone would do after picking up a spent casing from the ground, I looked at the headstamp. It read “REM-UMC 1906.” “Definitely old,” I said of the .30/06 casing that wasn’t even marked as a .30/06. “I wonder if ol’ Glaser smoked a ram from this spot.”

Frank Glaser, the legendary Alaskan hunter and trapper, was certainly no stranger to this country. He almost surely would have walked this very ridgeline at one point or another.

I’ve done a lot of wondering about Glaser, who hunted and trapped the very same places I do—a century before me. He arrived in Valdez at the age of 26, in May 1915. He had a packsack, some duffels, a new Winchester .30/06, and the same excitement any lower 48 hunter has upon arriving in the unspoiled wilderness of the North.

“Tales of Alaska always fascinated me,” Glaser says in his biography. “I was gripped by stories about Alaska’s fabulous big game, its great caribou herds, its giant bears, huge moose, and the white sheep that roamed sky-scraping mountains. Besides dreaming of hunting in Alaska, I yearned to trap the Territory for northern fox, mink, lynx, and marten.”

From Valdez, Glaser walked 371 miles north to Fairbanks, my hometown. This would be a hell of a long walk today, even with the paved highway.

That first adventure and all the epic ones to follow were reported by Alaskan and Outdoor Life writer Jim Rearden, who eventually wrote Glaser’s biography, Alaska’s Wolf Man. The book extols the ultimate Alaskan life of adventure—one that many of us still strive for today. It’s a lifestyle that depends upon hunting, fishing, and trapping not only as recreation, but also as a profession. This way of life is mostly lost in mainland America, but here in Alaska, it’s still possible.

Glaser became a true Alaska legend because of his pure grit and his wilderness experiences, which are almost too fantastical to be believed today—almost.

Meeting Silent Frank

Rearden had heard about Glaser well before he ever met the man. Locals referred to Glaser as “that federal wolf hunter. A genuine sourdough. An old-timer that old-timers respect.”

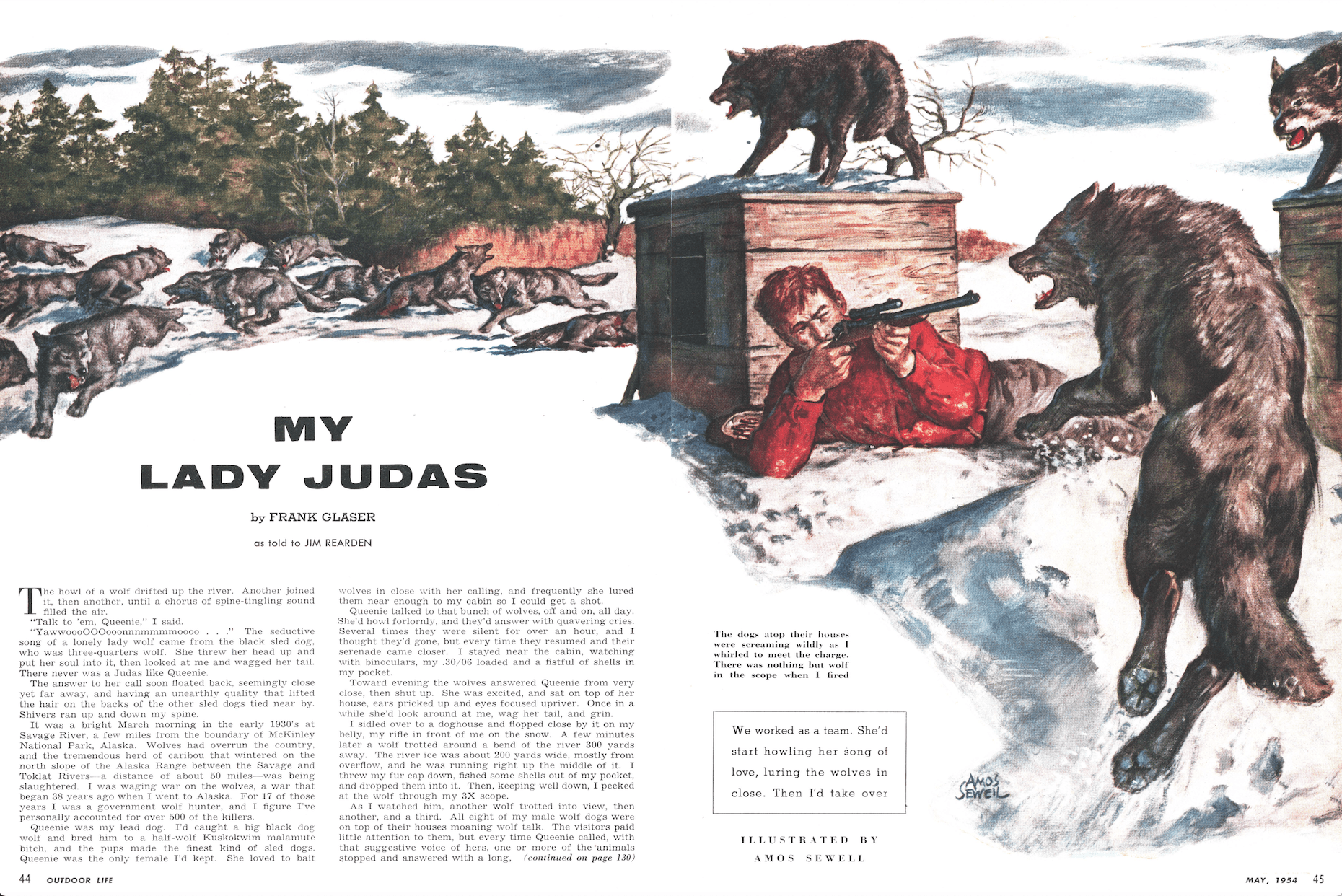

By the time Rearden caught up with him, Glaser had been a market hunter, roadhouse owner, dog-team freighter, trapper, wolf-dog breeder, big-game guide, and predator-control agent. Glaser possessed “an encyclopedic knowledge of Alaska’s wolves and other wildlife.” In one iconic tale, he used his favorite female wolf dog to howl in a pack of wild wolves.

Rearden first met Glaser in 1952 at Frontier Sporting Goods in Fairbanks, where “he spoke of moose hunts, charging grizzly bears, driving a team of wolf dogs, market hunting in the ‘old days,’ and other intriguing Alaska wilderness experiences.” A compulsive talker, Glaser was probably making up for years of living alone in the wilderness; some called him Silent Frank.

Glaser had moved into the Black Rapids Roadhouse (part of which still stands today) in 1915 when he was hired by the road commission to provide meat for crews building the Richardson Highway, which would connect Fairbanks and Valdez.

On Glaser’s first sheep hunt, he killed two rams and could have taken more, but he didn’t want to put more meat on the ground than he could pack out before it spoiled.

“I gutted the two rams and removed their heads and legs. I lashed one to my packboard, carried it to a nearby glacier, and cached it on the ice. It took the rest of the day to pack the other ram down the steep mountain and along the trail to Rapids. I got twenty-five cents a pound for sheep, caribou, and moose. Those two rams brought me more than $50, big money in 1915.… My first hunt set the pattern. I usually killed two sheep at a time, commonly caching one at a glacier, which are plentiful in the mountains near Rapids.… The rams I killed didn’t affect production of lambs, for one ram can cover ten to fifteen ewes, and plenty of rams were left. Few others hunted where I did, and game was wonderfully abundant.”

At Home in the Wild

A hundred years later, Schultz and I were sheep hunting Glaser’s old territory. As we slowly climbed our way up a steep canyon, we would jokingly say, “That looks like a good spot to sit. I bet ol’ Frank sat on that rock.” Talking about how tough Glaser must have been became our way of downplaying our own struggles on the mountain.

To this day, the Alaskan wilderness can throttle you, but Glaser was a master at surviving in this country—he had a nonchalant attitude toward hardship and danger.

In one instance, he fell through river ice and nearly drowned. This was in subzero temperatures. After escaping from the river, he almost froze to death. His journal entry for the day simply said: “Had a hell of a time crossing the river.”

But to me the most impressive thing about Glaser was his ingenuity. He had an incredible ability to solve problems in the bush under harsh conditions with minimal tools.

In August 1937, at 48 years old, Frank took an assignment to follow the Fortymile caribou herd—on foot. The migration would take him from Eagle, near the Canadian border, to the herd’s wintering grounds in the White Mountains, likely a 200-mile trip.

“I wore rubber-bottom leather-top shoepacks and summer weight woolen clothing, including a Filson wool mackinaw jacket. At first, I had several pots and pans but eventually abandoned all but one, in which I boiled the grayling I caught, and meat from caribou I shot,” Glaser recalls in his biography. By early September, it had started to snow, and Glaser “had to stop to prepare for cold weather.” This meant shooting three yearling caribou, brain-tanning the hides, and sewing them together to make a sleeping bag.

“How wonderful it was to sleep warm for a change. I used that sleeping bag for many years,” he wrote.

In another string of events described in a 1975 Outdoor Life feature titled “Adventure Was His Life,” Glaser was spending the fall trapping and hunting wolves in the Mount Hayes area of the Alaska Range when he was charged by a bear.

“He was carrying his current favorite rifle, a .220 Swift,” Rearden wrote. “He was 15 feet from a willow patch when with a roar a huge grizzly bear charged out of it. Frank shot from the hip, slowing the bear, but the tiny 48-grain bullet didn’t have the needed stopping power.

“The bear kept coming, and Frank shot again, leaped back, shot a third time, and leaped back once more. The bear slowed with each shot, but it kept moving. After dodging the bear several times and doing a lot of leaping and shooting, he finally dropped the animal with his 11th shot. It fell scarcely a rifle’s length away.”

The next two days were a marathon of brutality. We packed out the sheep close to 28 miles. We duct-taped the blisters on our feet, and our legs and backs were beyond sore.

Frank sat on the bear and had a pinch of Copenhagen snuff (or “Swedish Dynamite” as he called it) to steady his nerves. He skinned the bear and tanned the hide with sulfuric acid and salt. Deep snow made an airplane pickup impossible, and it was up to Frank to walk out more than 100 miles. He used his buckskin needle to sew from the grizzly hide a pair of mittens, a fur cap, and a pair of mukluks with soles of moosehide.

On the second day of his hike out, he broke through the ice on a river with the air temperature at minus 40 degrees. He fought his way ashore and ran to a nearby patch of spruces as his clothing froze. He started a fire and stripped, wearing nothing but the new bearskin cap, mittens, and the dry moccasins from his pack. He waved his wet clothes through the flames to dry them.

The Long Walk Home

On the opening morning of Schultz’s hunt, we woke to a soft white light outside our tent, which could mean only one thing: snow. It continued to fall all day, and -every half hour we would knock the heavy, wet stuff off our rain fly to keep the tent from caving in. Moving in that steep, rocky country is dangerous in the snow, but we eventually decided that we had to shift to a lower elevation before conditions got worse. We slowly retreated through the rocks to a more sheltered area. And from there we could spot small white clusters of sheep scattered on green hillsides below us.

As I sat in my synthetic puffy suit, watching rams through a spotting scope and pausing occasionally to spit Copenhagen into the snow, I couldn’t help but think about Glaser hunting these mountains with nothing but wool, canvas, and leather.

Schultz eventually got his sheep—a gorgeous ram with both horn tips broken off right at full curl. After a couple of blown opportunities, we found this one bedded beneath a boulder high on a ridge that looked like something out of a moonscape photo. A snow-white glacier loomed in the distance.

We circled the ram and made a steep climb to get above him. As other sheep began feeding out on the ribbons of green grass protruding from the sea of rock, he moved to a spot below us. At Schultz’s shot, we knew the painful amount of work before us.

After a few quick photos, we butchered the ram in the late-evening light and carefully picked our way down the hillside by headlamp. We caught the glimmer of the reflective guyline strips at about three in the morning.

The next two days were a marathon of brutality. We packed out the sheep close to 28 miles, and by about 10 the next evening, we were scraping the bottom of the barrel. We duct-taped the blisters on our feet, and our legs and backs were beyond sore. Buried among the contents of my 80-pound pack was that old .30/06 cartridge I’d found up on the ridge.

“What do you suppose Glaser would say if he saw us right now?” I asked as we bent over our trekking poles, trying to find the will to finish the last few miles of the hike. “He’d probably say, ‘Look at you sissies,’” Schultz joked.

We eventually staggered out to the road in the middle of the night and brought our adventure to an end. All that discomfort is just a dull memory now, but I can recall the feeling of standing on that high ridge, over Schultz’s ram, as vividly as ever. There’s a great disparity between what I’ve experienced in these wild places and what I can convey about those experiences through words and photos. I imagine that this was probably true for Glaser as well.

Looking back, I don’t think Glaser would have called us sissies after all. I think he would have gotten a roaring fire going and asked us about the ram we had. Then he probably would have told us a story or two about the old days.

This story originally ran in the Alaska issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.