We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

We take so much for granted as we go about our daily lives, seldom considering that in the blink of an eye fate could place us in a situation that will test our mettle-a situation where failure means death and even success will leave us indelibly changed. Such was the case for Pete Karels. One moment he was settling against the bole of a spruce tree, enjoying a peaceful sunset in the splendor of a remote Canadian wilderness. The next, he was face to face with the most dangerous animal in North America and almost certain death. His fate rested solely on how he would react in the ensuing seconds.

It all began a year earlier, when Karels’ friend and fellow Minnesotan, Ron Bice, invited him along on a bowhunting trip for moose in Alberta. Bice had hunted this region for black bear several times with guide Everett Martin, and over the years the two had become friends. Following one of these bear hunts, Bice and Martin decided to go after moose the coming season; upon returning to his home, Bice asked Karels to join in. They planned their adventure in the intervening months, and when September finally arrived the duo gathered their gear, loaded up their truck and made the long trek from Minnesota to Alberta.

Along the way, Karels read an article about pepper spray for bears. He told Ron about it one morning over breakfast. Bice said, “I’m gonna get some of that. How about you?”

Karels replied, “No, it’s sixty dollars.” Then he drolly added, “Besides, more than likely I’ll be hunting with you, and I know I can outrun you.”

Upon arriving at camp, Karels and Bice met their outfitter and discussed their plans. They would be hunting from tree stands, overlooking natural mineral licks. These minerals are an important dietary supplement for moose; the animals are drawn to low muddy swales where the licks are concentrated. Bice and Karels spent the first day scouting licks, hanging stands and cutting shooting lanes. With their mission accomplished, they headed back to camp for dinner.

As is often the case in that part of the world, the subject of grizzlies came up while the hunters ate. Martin and some of the other guides related various tales of grizzly encounters to a captivated audience. Having grown up in the area, Martin was familiar with the big bears, and though he respected them, he did not fear them.

By the light of the glowing lantern, Martin offered some advice to his wide-eyed clients on how to react should they encounter a bear. “Forget what the books tell you,” he said. “Your best chance is to stand your ground and try to act bigger and meaner than the bear.” Even after hearing the guides’ stories, Bice thought the odds of a grizzly encounter were extremely remote. Karels summarily dismissed the idea. Still, both kept Martin’s advice in mind during the hunt.

“To be honest, I was looking for grizzly tracks from the very start,” said Bice. Seeing no evidence of the big bears the first day put him more at ease. “I felt an encounter was unlikely, which boosted my confidence to walk through the brush with only my bow and arrows.” While Karels maintained his nonchalant attitude about the bears, he sensed Bice’s trepidation. It became a running joke between the two. “That night old Pete was teasing me about my fear of and respect for these bears. He laughed and joked about it pretty much throughout the hunt,” said Bice.

The days passed with no moose sightings, but each night there was more grizzly talk among the hunters and their guide. Their discussions took on a more serious tone when a problem bear was reported within four miles of camp. Hikers had encountered the bear over a moose kill. Because it was on a hiking trail and roughly a mile outside the town of Hinton, the bear was classified as extremely dangerous; people were advised to steer clear of the area. The bear was eventually tranquilized and relocated 200 miles to the north.

With that potential danger removed, fear of the bears once again subsided, until Bice noticed some fresh sign near one of his moose stands. It was a rubbing tree, the kind bears sometimes use to scratch their backs and perhaps deposit scent. The tree was covered with coarse grizzly hair. It was also right on the half-mile trail that Bice had to travel each day walking to and from his stand. Bice admitted that his bow and arrows offered little comfort on those daily walks, particularly at night in the dark. “For the first time in my life I knew what it felt like to be potential prey for something,” he said. Meanwhile, Karels continued to make light of his partner’s growing concern.

Whether it was his respect for the bears or the lack of moose sightings, Bice decided to shift his attention to a different stand, some 30 miles from where he’d been hunting. The choice ultimately turned out to be a good one. That evening Bice had his first chance at a big bull. “Shortly after getting settled in, I heard a loud crash to my left,” he said. “It was a cow and calf coming my way, passing by about 20 yards out.” A few minutes later he heard the grunting of a bull approaching on the same path. The 40-plus-inch rack of the bull materialized out of the dense spruce, as the moose headed straight for Bice.

“I couldn’t draw the bow because he seemed to be staring straight at me the whole time as he came closer, approaching straight-on.” The bull eventually stopped at the base of Bice’s tree, a mere 6 feet away. “I couldn’t believe he hadn’t heard me hyperventilating,” said Bice. Astonishingly, the bull never offered Bice a clean shot. Now the Minnesotans were down to their last day of hunting.

With the final day of his clients’ hunt looming and nothing to show for it, Martin offered to let the pair stay on another couple of days. Bice decided to take advantage of the extra time by catching up on some much-needed sleep. He suggested that Karels head back to the site of his most recent moose encounter, hoping the big bull would return and perhaps offer him a better shot.

The afternoon passed without event, however. Karels planned on hunting again the next morning, and because Alberta law doesn’t allow hunters to carry a bow on a four-wheeler until noon, he decided to leave his bow in the stand. He also considered leaving his fanny pack, but almost as an afterthought, he remembered Martin’s advice. If he should encounter a bear, the air horn he carried in his pack might deter it.

After a three-quarter-mile hike to the road, Karels arrived at the pick-up spot. Another of the camp’s guides, Dan Abei, was scheduled to pick him up at 8 o’clock. Karels was early so he decided to lie down in a little hut the outfitter had made out of evergreen boughs. His repose was short-lived, however. Barely five minutes had passed when, lying on his side and looking up the four-wheeler trail, Karels suddenly perceived a horrifying sight: a full-grown sow grizzly, with two cubs in tow, headed straight for him. Their eyes met, both becoming aware of the other’s presence at the same instant.

Karels was overwhelmed with a feeling of helplessness, but he knew he didn’t want to be lying down. He scrambled to his feet. Whether because of his sudden movement, their proximity or perhaps both, when Karels stood, the bear charged.

There was no time for fear. Karels acted on instinct and adrenaline. With 600-plus pounds of pure fury bearing down on him, and his life hanging in the balance, he had to make a split-second decision. His initial, gut instinct was to go behind the hut, but as he turned and took half a step the outfitter’s advice raced through his mind: “Don’t ever run from a grizzly bear.”

Most people wonder how they would react in a life-or-death situation. Animal behaviorists call it a fight-or-flight response. Soldiers call it trial under fire-the test of battle. Karels now faced that test. He turned back toward the bear, then waved his arms and yelled with all the force he could muster.

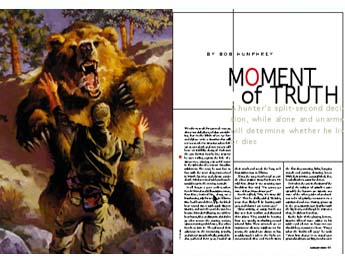

The bear, perhaps taken aback at Karels’ audacity, checked her bluff charge. Standing mere feet from Karels, she rose up on her hind legs, towering over him, and let out a roar that shook Pete to his very marrow. Meanwhile the little 150-pound cubs had also stood up and were now bouncing on their hind legs, as if to say, “Go get him, Mom, go get him!” Somehow, Karels stood his ground.

To an onlooker, the scene might have seemed almost comical, had it not been so frightening. Here was a man, 6 feet 3 inches tall, weighing 220 pounds, trying to face down a bear that towered three feet over him and was nearly three times his weight. Both were standing, staring at each other, screaming and roaring and flailing their arms. Saliva, snot and the foul odor of bear breath filled the tiny space between them. But the bear came no closer.

Karels turned slightly and reached down for his fanny pack and the air horn inside it. As soon as he did, the bear dropped to all fours and got ready to charge again. Karels frantically pulled the air horn from his pack, then came to the horrific realization that the horn was still in its plastic container. Screaming at the bear, Karels desperately tried to free the horn. That screaming gave him the few extra seconds he needed. Just when it seemed the bear would lunge forward, Karels freed the horn and blasted her.

It startled the bear momentarily and, still standing, she backed off. Then, to Karels’ dismay, the horn quit, and the bear came at him again. Karels challenged her once more. Roaring and advancing on her, he managed to tighten the top and get the horn working again. The bear backed down, turned and headed away. By now adrenaline was surging through Karels’ body and he chased after the bear, yelling and blowing the horn. He had seemingly escaped with his life, but the bear was not done with her terrorizing.

No sooner had she disappeared from Karels’ sight than Abei came riding up on his four-wheeler. Both bear and four-wheeler rounded the same corner at the same time. “I saw a flash of gray go through the bushes and thought it was too small to be a moose,” Abei later related. “First I saw a cub, then the sow. She reared up and roared. Spit was coming from her mouth. I reached for my rifle, but I didn’t know if Pete might be somewhere behind her in the bush.” The bear hesitated, turning from Dan back toward Pete. Then she dropped to all fours and, choosing flight over fight, hurried her cubs uphill and out of view.

When Dan finally got to Pete he was so stunned he appeared almost calm, except for his ghostly white complexion. “Did you see the bear?” Dan excitedly asked, breaking Karels’ trance. “She charged me; she charged me!”he test of battle. Karels now faced that test. He turned back toward the bear, then waved his arms and yelled with all the force he could muster.

The bear, perhaps taken aback at Karels’ audacity, checked her bluff charge. Standing mere feet from Karels, she rose up on her hind legs, towering over him, and let out a roar that shook Pete to his very marrow. Meanwhile the little 150-pound cubs had also stood up and were now bouncing on their hind legs, as if to say, “Go get him, Mom, go get him!” Somehow, Karels stood his ground.

To an onlooker, the scene might have seemed almost comical, had it not been so frightening. Here was a man, 6 feet 3 inches tall, weighing 220 pounds, trying to face down a bear that towered three feet over him and was nearly three times his weight. Both were standing, staring at each other, screaming and roaring and flailing their arms. Saliva, snot and the foul odor of bear breath filled the tiny space between them. But the bear came no closer.

Karels turned slightly and reached down for his fanny pack and the air horn inside it. As soon as he did, the bear dropped to all fours and got ready to charge again. Karels frantically pulled the air horn from his pack, then came to the horrific realization that the horn was still in its plastic container. Screaming at the bear, Karels desperately tried to free the horn. That screaming gave him the few extra seconds he needed. Just when it seemed the bear would lunge forward, Karels freed the horn and blasted her.

It startled the bear momentarily and, still standing, she backed off. Then, to Karels’ dismay, the horn quit, and the bear came at him again. Karels challenged her once more. Roaring and advancing on her, he managed to tighten the top and get the horn working again. The bear backed down, turned and headed away. By now adrenaline was surging through Karels’ body and he chased after the bear, yelling and blowing the horn. He had seemingly escaped with his life, but the bear was not done with her terrorizing.

No sooner had she disappeared from Karels’ sight than Abei came riding up on his four-wheeler. Both bear and four-wheeler rounded the same corner at the same time. “I saw a flash of gray go through the bushes and thought it was too small to be a moose,” Abei later related. “First I saw a cub, then the sow. She reared up and roared. Spit was coming from her mouth. I reached for my rifle, but I didn’t know if Pete might be somewhere behind her in the bush.” The bear hesitated, turning from Dan back toward Pete. Then she dropped to all fours and, choosing flight over fight, hurried her cubs uphill and out of view.

When Dan finally got to Pete he was so stunned he appeared almost calm, except for his ghostly white complexion. “Did you see the bear?” Dan excitedly asked, breaking Karels’ trance. “She charged me; she charged me!”