We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Someone once said that if you aren’t casting bullets on your own then you really aren’t reloading. There’s a lot of truth to that. Most reloading of handgun, rifle and shotgun ammo is like baking a ready-mix cake-you just dump in the ingredients according to the instructions and the results are pretty much predetermined.

Casting bullets, however, gives you control of a whole new dimension of reloading and ammo performance, with virtually limitless variables and possibilities.

Hand-cast lead bullets, of course, go back hundreds of years before the appearance of jacketed bullets. (It was not until well into the 20th century that jacketed bullets equalled the accuracy of fine lead bullets cast by hand.) The great bison slaughter of the 18th century was carried out with cast-lead bullets. Hunters would retrieve bullets from buffalo carcasses, then remelt and recast them over campfires and kill more buffalo with the same lead the next day. Nowadays there are hunters who still prefer cast-alloy bullets for their hunting pistols and rifles, and a number of rifle competitions are limited strictly to cast-lead bullets. With a good rifle and expertly cast bullets, sub-minute-of-angle accuracy is possible at considerable distances.

Cast-Bullet Advantages

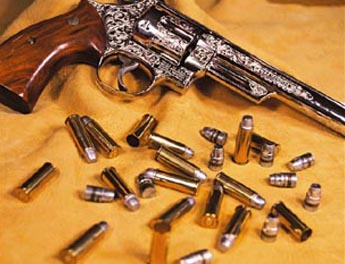

It is among handgunners, however, that cast-lead bullets are most widely used. This is for several reasons, the most common being economy. With 10 pounds of scrap wheel weights, which can be found cheap or free at most tire and auto service shops, you can cast over four hundred 150-grain, .38-caliber bullets or nearly three hundred 240-grain bullets for your .44 Magnum.

There is a common but mistaken notion held by some shooters that cast bullets are naturally inferior to jacketed bullets and are fit only for casual plinking. Such opinions have probably been caused by the poorly cast bullets that some shooters seem content to load and shoot and also by commercial cast bullets that sometimes are of poor quality. Also, cast bullets have a reputation for causing an ugly condition called “leading”-hard-to-remove traces of lead in the barrel resulting from bullet friction. (The lubrication grooves in cast bullets are designed to minimize this.) This situation, like almost all the other misinformation spread about cast bullets, is simply the result of faulty casting and preparation techniques.

The fact of the matter is that lead- alloy bullets, when correctly prepared and loaded, can measure up to very high standards of accuracy and performance. There are legions of hard-core handgunners who depend on their cast bullets for top accuracy in target competitions and would never dream of firing anything else in their highly tuned target pistols. Also, there are lots of handloaders who simply enjoy the process of casting bullets. It’s very soul-satisfying to open a mold and drop out a gleaming bullet that only moments before was silvery soup.

Unlimited Possibilities

Another advantage of casting bullets on your own is the tremendous variety of shapes and sizes available. Checking the catalogs of four major suppliers of bullet molds (Lee Precision, Lyman, RCBS and Redding), I found more than 35 different shapes and weights in .38/357 caliber alone, plus more than 30 more in .44 and nearly 50 in .45 caliber. That’s without counting the dozens of other designs in calibers from .22 up to .50. And if you don’t like the available shapes and sizes, you can design your own and have a mold custom-made. There is almost as much variety in the prices of bullet molds, ranging from $19.98 for the inexpensive-yet- excellent Lee single-cavity mold to over $300 for a Redding/SAECO eight-cavity masterpiece.

When casting rifle bullets for top accuracy I’ve always preferred a single-cavity mold so that all bullets are identical, but for high-volume handgun shooting a multiple-caty mold like the 4-cavity job shown on these pages saves lots of time.

For target shooting, the most popular designs are wadcutters or semi-wadcutters-so-called because they punch crisp, clean-edged holes in paper targets. There are round-nosed designs for slick feeding in autoloaders and even hollow-point molds for better expansion on game. Take your pick. As I said earlier, the variables and possibilities are limitless.

What to Buy

Casting bullets can be as simple and inexpensive as you want to make it. Old-time buffalo hunters melted lead over a campfire, and you can do about the same with a camp stove. You can even melt lead and cast bullets over a kitchen range, but don’t tell your wife I said so. (And be sure to turn on the exhaust vent or she’ll really get mad.) Simple lead melting pots are cheap, and the only other tool you’ll need, aside from the mold, is a side-pour dipper. The bullets you can cast with simple, inexpensive equipment will be every bit as good as those made with costlier and more elaborate models.

Using an electric casting furnace is a lot more comfortable than toiling over a hot stove, and some electric furnaces, such as those offered by Lee Precision, are quite inexpensive. Pay a bit extra and get one with a temperature control-you’ll be glad you did. The main benefits of the fancier equipment, such as the RCBS Pro-Melt bottom-pour furnace I’ve used for a quarter-century, are speed, temperature control and large capacity (more than 20 pounds). Of course, they also cost more and mainly appeal to high-volume bullet casters. My suggestion for beginners is to start off with a moderately priced, thermostat-controlled furnace.

Finishing Tools

The only other equipment you’ll need is a sizer-lubricator with sizing die(s). This apparatus sizes the bullet to the correct diameter and perfect roundness and fills the bullet’s lube grooves with lubricant. These tools are made by the aforementioned makers of cast-bullet equipment. Prices and operation vary widely. As a caster of your own bullets, you’ll soon discover that you can make dramatic improvements in handgun accuracy simply by experimenting with bullet diameters-something you can’t do with jacketed bullets. Likewise, fiddling with different lubricants, or even concocting your own, can result in better performance.

Though the likes of Natty Bummpo and Dan’l Boone cast their round bullets of pure lead, it’s not so good for modern-day pistol bullets. For one thing, pure lead is too soft for modern pistol loads and it doesn’t cast cleanly in some complex bullet designs. This is why lead should be alloyed with a small percentage of tin to make the bullets harder and better-cast. Adding a trace of antimony to the lead-tin alloy makes them even harder.

Adding Alloys

A good all-purpose alloy for both pistol and revolver bullets is 10 parts lead to one part each of tin and antimony. Depending on your source of lead, which might be scrap cable sheathing, lead pipe or odd scraps of lead of unknown alloy, you can make a good workable alloy by adding one part tin. An easy source of tin, by the way, is plumber’s solder. Adding one part tin to wheel weights, which already contain antimony, makes good hard bullets. Sometimes wheel weights are a workable alloy once they are melted, fluxed and skimmed.

One of the hardest and most accurate alloys for casting bullets is linotype metal, which is 4 percent tin and about 11 percent antimony. It can be bought at some print shops or as scrap. It is usually a good bit more expensive than scrap lead, but it makes great bullets if you want top accuracy. Note, however, that scrap linotype may have had the tin component burned out by frequent remelting and may need tin added for best casting.

Getting Started

When you first melt a batch of dirty lead scrap alloy, such as wheel weights, a lot of cruddy-looking stuff will float to the molten surface. Stuff like the steel clips of wheel weights can be skimmed off, but be careful not to remove the stuff that looks like cruddy scum because it may be an essential-but only separated-part of the alloy. Getting it all back together and further cleansing the alloy calls for fluxing. This is a simple and quick process accomplished by tossing small slivers of beeswax or candle wax into the pot and stirring the melt from bottom up. These fluxes make a lot of smoke (tossing in a burning paper match reduces smoke and smell), which is why I prefer fluxing with Marvelux (available from Brownells), a commercial flux in powder form that doesn’t smoke or stink up the place.

After fluxing and skimming off the remaining crud, you’re ready to begin casting. Unless, of course, you do what I like to do, which is run the newly cleaned and re-alloyed lead into ingot molds for later use. This is a good idea when you’re preparing a large batch of casting metal and want the whole lot to be uniform.

First Casts

Of course, new casters with a new mold always want immediate results, so go for it. With the alloy well-fluxed, simply dip into the melt with your side-pour dipper, hold the mold to the side, put the dipper spout to the mold’s sprue hole and rotate them together to a vertical position so that the melt runs into the mold. Then pour a generous puddle of alloy on top of the sprue to allow for shrinkage inside the cavity as the alloy cools and hardens. This will help avoid cavities in the bullet base, a common cause of poor accuracy and a sure sign of poor casting technique.

In a few seconds the alloy will harden and the mold will be ready to open and give forth a newborn bullet. I use a stick of hardwood to whack the sprue cutter open. Don’t use a metal hammer to hit the sprue cutter or you’ll damage it. The first bullets out of a cold mold usually look like silver-plated prunes, all wrinkly and ugly. But as the mold heats up, the alloy will flow more freely and the bullets will come out sharp. Sometimes it takes a while for oil or other preservatives to burn out of a mold (another cause of wrinkled bullets), so clean them well with a solvent before use.

If your bullets have a frosty appearance it means the mold is too hot. This is corrected by reducing the temperature of the melt and/or slowing down your rate of casting so that the mold cools between pours. A trick I like is to use two molds at once, alternating pours so they have more time to cool and for the alloy to solidify. The bullets are still rather soft and tender as they come hot from the mold, so catch them on something cushiony like several layers of cotton towels.

After casting a batch of bullets and allowing them to cool down enough to touch, do a carefulscrap alloy, such as wheel weights, a lot of cruddy-looking stuff will float to the molten surface. Stuff like the steel clips of wheel weights can be skimmed off, but be careful not to remove the stuff that looks like cruddy scum because it may be an essential-but only separated-part of the alloy. Getting it all back together and further cleansing the alloy calls for fluxing. This is a simple and quick process accomplished by tossing small slivers of beeswax or candle wax into the pot and stirring the melt from bottom up. These fluxes make a lot of smoke (tossing in a burning paper match reduces smoke and smell), which is why I prefer fluxing with Marvelux (available from Brownells), a commercial flux in powder form that doesn’t smoke or stink up the place.

After fluxing and skimming off the remaining crud, you’re ready to begin casting. Unless, of course, you do what I like to do, which is run the newly cleaned and re-alloyed lead into ingot molds for later use. This is a good idea when you’re preparing a large batch of casting metal and want the whole lot to be uniform.