Sleeping was impossible. I couldn’t hear them and that worried me. The sound that rivals the lion’s roar and the howl of the wolf-the most glorious sound in the natural world-was missing. The bull elk should have been making the golden aspen leaves tremble with their bugles, but the stream rushing down from Vampire Falls was the only sound that came back to me in the darkness. Daybreak was still hours away, so, like a child anxious for Christmas morning, I waited and wondered what the gray edges of dawn would bring.

Our little tent camp was high in the Navajo basin of southern Colorado, snuggled in the fir trees just below the cliffs. The place hadn’t been hunted for many years and it was smack in the middle of the best elk territory in the United States. The license I had drawn made it “mine” in that I would be the only one to explore this vast ranch as a future guiding territory, the one who had to find out if the bulls were really there. This wasn’t about raghorns or five-points, but about the mighty bulls of the woods. And it would be a grand treasure hunt. If the promise of elk and the magnificence of the land were not enough to make this hunt spectacular, my guide was. Pat Lancaster is a quiet, understated fellow who has simply spent his entire life hunting big bulls, guiding for big bulls and living for big bulls. He was the perfect complement-friendly, bright and openly in love with elk hunting. And with a grunt tube and a diaphragm, he could speak elk fluently.

When Pat finally rustled in his bag I was glad not to be alone in my torment.

“Can you hear anything?” I whispered.

“No, just the water in the creek,” he said. “I think the creek is drowning their bugles. They have to be here.” That was it-coffee, hotcakes, then away from the babbling, rushing torrent. We had to know. It was early October, no hunter had disturbed them and yesterday we saw every sign that some serious bulls had been at work. There were wallows in the springs and most of the fir saplings looked as if the grim reaper had been playing gardener. The bulls had to be bugling; we just hadn’t heard them yet.

We waded the creek in darkness, climbed the aspen- covered hill above and dropped into an evergreen pocket on the far side. It was still as black as the inside of a cow when it happened-the low notes, ending in a shrill scream. The sound seemed to consume everything around us. In the total blackness, it seemed, for a moment, to be all there was. A serious bull had warned whatever approached that he was not to be tread upon. There was nothing to do except hold our breath and settle quietly to the ground. We were right on top of him.

The old bull bugled once more during the year it seemed to take for the sky to turn gray. When there was enough light to see we began to take stock of the situation. Thick evergreens were on three sides with an open aspen meadow just in front-the ideal spot for a bull to play before the sun touched the treetops. Pat made a tiny, almost inaudible, mew on his cow call…nothing. Another mew, louder this time and the trees shook. He came alone, holding his head high and almost strutting on stiff front legs. He was perhaps a four-year-old, moderately heavy in the body with six points on a side. Our friend was lonely and for all he knew a lady had called.

Pat cow-called again, this time with more depth and passion, and again the bull made sure his lonely cow knew where he was. He rolled his antlers back along his sides and opened his mouth wide and his sides heaved as the sound and steam bellowed from his throat. Our goal was to find a fellow twice his age, but he offered the chance to play with a good bull. Pat tucked the end of the grunt tube under his arm, pointing the opening away from the bull, and mewed again. Even though I was at his side, it sounded as if the cow was 50 yards behind us. The bull was tiptoeing now, searching for his st love. At the moment he was a medium shot away-medium with a bow and arrow.

Pat grinned, bent the tube to his left and made the anemic squealing bugle of a spike. The bull instantly snapped his eyes to where we were hiding and screamed. Again the yearling interloper squealed and the big bull trotted forward. The cow mewed from behind and the spike squealed. At 15 steps what I was seeing and hearing could only be described as unpleasant. There was a blackness in the bull’s eyes and they did not seem to focus, and the trilling, musical bugle heard earlier had turned into a single-note raging scream. We were staring primeval hate right in the eye. I would not have liked to be the spike he imagined was threatening his love life. As it was, it was time to let him know what we were. As we stood he jumped backward in stunned disbelief, then the look returned. There was a reasonable chance he would take his revenge on us. Thankfully, he loped into the timber.

During the next few minutes, Pat filled in the details on his university-level performance. “The cow call is versatile, it can be ‘thrown’ just like a ventriloquist’s voice and you can manipulate elk with it,” Pat said. “When you bugle, they know exactly where you are; all of the cards are instantly on the table. Never bugle if the situation is the least bit shaky. The bugle is a last resort.”

Two other bulls called during the next few hours, but they continually moved higher into the heavy timber. These were bulls with harems. They were following old lead cows and at the moment did not care for a stray in the background.

The sun was high, streaming through the aspens. The morning of “bugle” hunting should have been over. Then a deep groaning roar, almost muted by the rushing waterfall, changed the day forever. Pat snapped to attention. The play was over.

“That’s him,” he said.

“What?” I asked. I had not heard it before.

“It’s a moaner,” Pat said happily. “If we see him, I bet you shoot him.”

We stood in silence until the bull called again. He was distant, far above Vampire Falls. The first leg of our rush took us through aspen blowdowns. The trees were huge, stacked four feet deep at times. When the Lincoln Logs gave way, a wall shot up. A switchback trail led us up several hundred vertical feet, without taking us forward more than 100 yards. We climbed and panted, while the old fellow’s occasional roars urged us on.

Oh, So Close

The scene above the crest took our remaining breath away. Behind us a vast valley rolled away into the distance. Before us lay a perfect park. The yellow aspens were evenly spaced, broken by clumps and slashes of young fir. The ground was almost flat, with little undulating hills. Vampire Falls hissed at our elbow. His call was clear and close now. There were no high notes, just a deep groaning roar. The delicate cows, with their yellow rumps and spindly chestnut necks, mewed and tweeted as they fed. Mixed with the higher-pitched calls of the calves, the orchestra sounded like a pod of humpback whales.

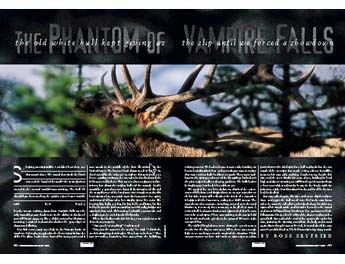

Single elk drifted in and out of view, then suddenly a great, white side appeared. His legs and belly were nearly black, contrasting with an almost Palomino body. He took another step and we could see that his beams were heavy and long, with a spread that looked to be 50 inches or more. I settled the crosshairs in his direction, just as he slipped behind a fir. The bull moved almost constantly but never in the clear. Once he stopped with his hips exposed, but one does not do that to a bull…even with the .416 Rigby. In spite of the gentle pleading from Pat’s call, they moved on. It was noon and they wanted shade in the big timber above. “We won’t push him,” Pat said. “This is elk heaven, this is their home. They’ll be back tomorrow.”

Our backtrack led down and through the jumbled aspens. The afternoon dragged along. The evening vigil above the pretty meadow seemed long and the night seemed longer. Tucked in my bag, I had visions not of sugarplums, but of a great white brute with long ivory tines.

When the morning sky turned pink again we climbed and he roared. True to Pat’s prediction, the elk had returned. The old fellow was there, but now two more bulls bugled in the same area.

The elk were lower, quietly feeding just below where they had been the day before. The peace was shattered by the crash of horns and a terrible frightened squeal. The old fellow had ushered another bull off his mountain with one mighty blow and perhaps a stab in the backside for good measure. It was time to crawl and slither.

Slither Time

Old cows with sharp eyes and invincible nostrils threatened our every move. A young bull to our left was our greatest ally, making plenty of noise. All we needed to be was invisible. The great brute from yesterday appeared about 75 yards away. But he gave us only a brief glimpse. Before we could close in, three cows fed across our front. We shed our packs and crawled again, moving toward where he had been. Then the demon appeared. We saw her ear first, then her front leg and left eye. She knew the enemy was at hand, but she wasn’t sure enough to bark the alarm. Seconds passed, then minutes. How long could we hold our breath? At last she fed away.

An old log was 20 yards above us. It was just about to give us a comfortable place to hide and catch our breath when another cow stepped out of the fir thicket. Weasel time. Two 6-foot, 200-pounders would have to fit into the three-inch gap under the log. Her right front hoof was close enough to touch. The cows mewed, the young bull bugled and from time to time the old fellow rattled the timber with his roar. My hands shook and the sweat rolled into my eyes. Again, after what seemed like an eternity the threatening cow strolled on. From our gopher-like vantage point, looking under the fir boughs, a big black leg appeared, then another, striding just behind a little belt of trees. He was 25 yards away.

I turned the Mauser safety and leveled the Rigby at the edge of the screen of fir. Two more steps and it would be over, but he did not appear. We crept to where he had been, only to hear his roar 50 yards farther above. He was like smoke. He did not expose himself, ever.

Most of the cows were above us, too. They had begun to work their way up into the heavy timber. Pat tried a more active roll, cow-calling very gently. The bull would roar in response, but nothing could seduce him away from his harem of some 30-odd cows and calves. Pat began to increase our gamble with spike-squeals. This was effective enough to make the bull keep careful track of the tail end of his harem. He remained close to the rear as they began a single-file climb d along. The evening vigil above the pretty meadow seemed long and the night seemed longer. Tucked in my bag, I had visions not of sugarplums, but of a great white brute with long ivory tines.

When the morning sky turned pink again we climbed and he roared. True to Pat’s prediction, the elk had returned. The old fellow was there, but now two more bulls bugled in the same area.

The elk were lower, quietly feeding just below where they had been the day before. The peace was shattered by the crash of horns and a terrible frightened squeal. The old fellow had ushered another bull off his mountain with one mighty blow and perhaps a stab in the backside for good measure. It was time to crawl and slither.

Slither Time

Old cows with sharp eyes and invincible nostrils threatened our every move. A young bull to our left was our greatest ally, making plenty of noise. All we needed to be was invisible. The great brute from yesterday appeared about 75 yards away. But he gave us only a brief glimpse. Before we could close in, three cows fed across our front. We shed our packs and crawled again, moving toward where he had been. Then the demon appeared. We saw her ear first, then her front leg and left eye. She knew the enemy was at hand, but she wasn’t sure enough to bark the alarm. Seconds passed, then minutes. How long could we hold our breath? At last she fed away.

An old log was 20 yards above us. It was just about to give us a comfortable place to hide and catch our breath when another cow stepped out of the fir thicket. Weasel time. Two 6-foot, 200-pounders would have to fit into the three-inch gap under the log. Her right front hoof was close enough to touch. The cows mewed, the young bull bugled and from time to time the old fellow rattled the timber with his roar. My hands shook and the sweat rolled into my eyes. Again, after what seemed like an eternity the threatening cow strolled on. From our gopher-like vantage point, looking under the fir boughs, a big black leg appeared, then another, striding just behind a little belt of trees. He was 25 yards away.

I turned the Mauser safety and leveled the Rigby at the edge of the screen of fir. Two more steps and it would be over, but he did not appear. We crept to where he had been, only to hear his roar 50 yards farther above. He was like smoke. He did not expose himself, ever.

Most of the cows were above us, too. They had begun to work their way up into the heavy timber. Pat tried a more active roll, cow-calling very gently. The bull would roar in response, but nothing could seduce him away from his harem of some 30-odd cows and calves. Pat began to increase our gamble with spike-squeals. This was effective enough to make the bull keep careful track of the tail end of his harem. He remained close to the rear as they began a single-file climb