We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Last month, U.S. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke announced that this year more than $1.1 billion will be distributed to state wildlife agencies from taxes generated by the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (widely referred to as the Pittman-Robertson Act) and the Dingell-Johnson Sport Fish Restoration Act.

The importance of these funds should not be overlooked. The two acts apply excise taxes on manufacturers of guns, ammunition, archery equipment, and fishing equipment, which are then put into conservation efforts. The system is credited with restoring a variety of wildlife species and conserving millions of acres of habitat. But, with a slow decline in hunting, these funds could be in trouble, and there are new efforts to recruit and retain new hunters and shooters, and therefore keep the funding programs healthy.

How the Taxes Work

The levies are regarded as ideal “user-pay, user-benefit” funding mechanisms in financing habitat rehabilitation, expanding access to public lands, and providing hunters and anglers with political clout in influencing conservation policies.

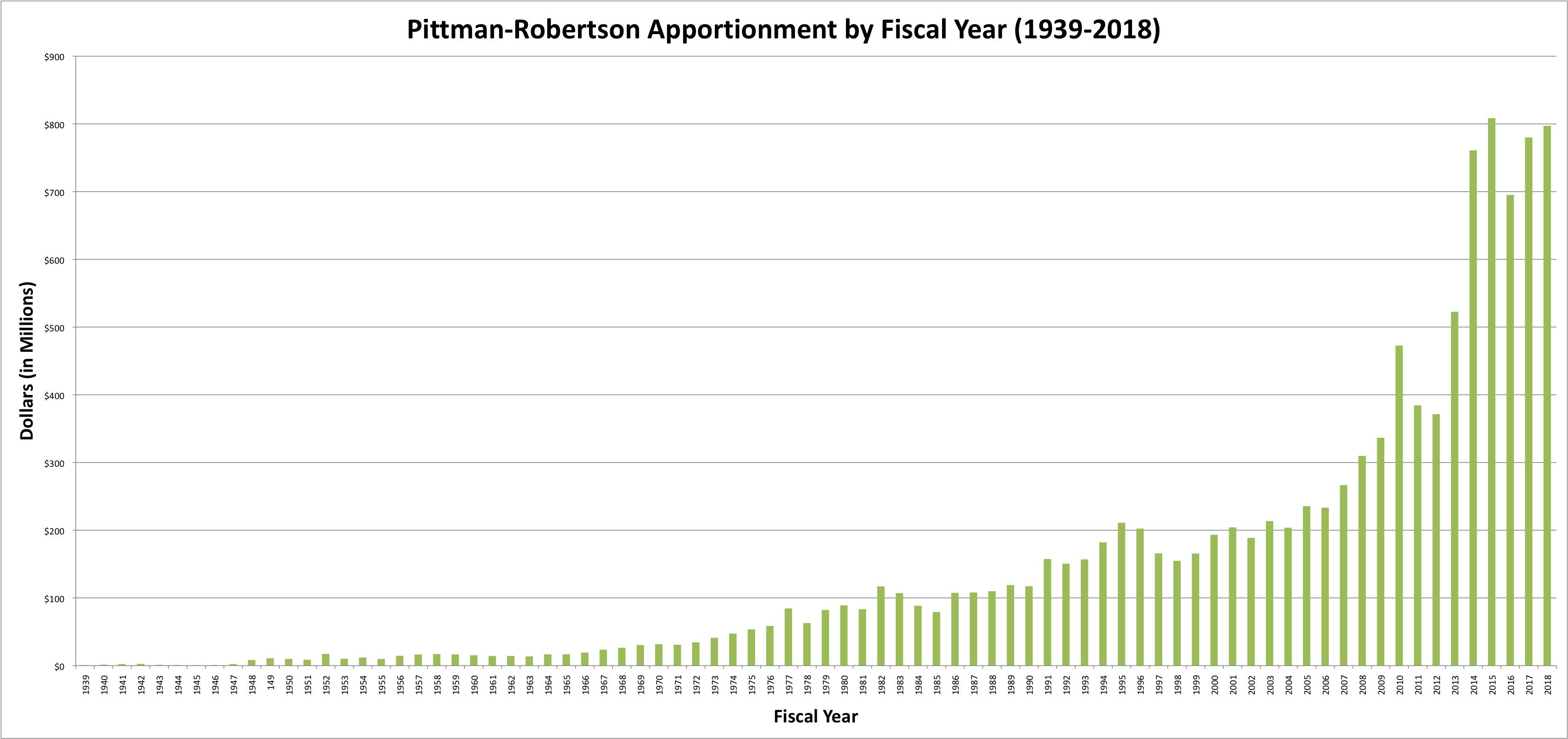

Since the first annual apportionment of $890,000 in 1939 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the agency has distributed more than $20 billion from the two federal excise taxes for state conservation and recreation projects.

“Pittman-Robertson dollars are the backbone of a uniquely American model of wildlife funding,” says Jeff Crane, President of the Congressional Sportsmen’s Caucus. “It has helped everything from wood ducks, wild turkey, bison, deer.”

The Pittman-Robertson Act (P-R) increased an existing 10-percent gun-and-bullet tax by one percent and dedicated the proceeds to the USFWS to apportion to states during a time when Congress was slashing taxes. It has generated more than $11 billion for conservation since 1939.

One of the P-R’s greatest strengths is its $3-to-$1 federal-state match, which requires states to pony up $1 for every three federal grant dollars. This practice discourages state legislators from sweeping revenues generated by licenses and fees—which are state wildlife agencies’ primary source of funding—into the general fund.

“It protects state wildlife agency license fee revenues because without those dollars’ full commitment, the state would not qualify for P-R dollars,” says Ryan Bronson, director of conservation for Vista Outdoor, a national manufacturer of some 50 brands whose sales generated $87 million in P-R taxes in 2017.

“The advantage of not getting general fund money from the Legislature is they can’t take that money away,” says Mike Schlegel, conservation committee chairman for Pope and Young and a retired Idaho Department of Fishing and Game wildlife biologist.

The enduring utility of both funds is their flexibility. P-R dollars are used for habitat acquisition and restoration, research, surveys, educational programs, project-specific staffing, and access leases.

“Here’s a waterfowl impoundment. There’s a skeet range,” Crane says. “It’s everywhere if you really look at it.”

A Long Decline

P-R also requires USFWS to allocate at least $8 million a year for enhanced hunter education programs and public shooting ranges. Yet the segment of P-R allocations dedicated to sustaining the shooting sports is a topic of growing debate, particularly as the number hunters decline.

According to a USFWS report published in August 2017, The 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, from 2011 to 2016:

- The number of hunters fell by 2.2 million participants.

- Big game hunters fell by 20 percent.

- Hunting-related spending decreased by 29 percent.

- Hunting equipment purchases slipped by 18 percent.

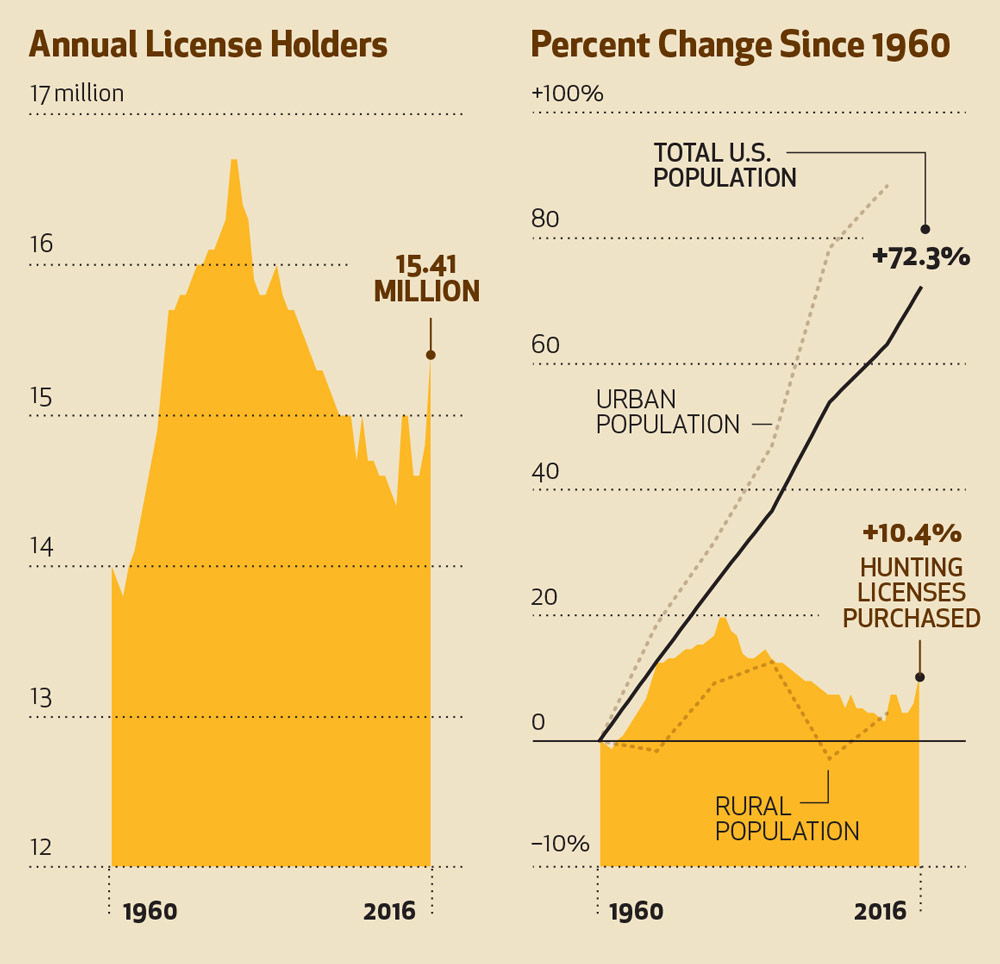

This decline in hunter numbers has been the norm since participation peaked in 1982 with nearly 17 million hunters. Meanwhile, hunter expenditures— a category that includes purchases of P-R-taxed sporting goods—are down. The 11.5 million people who hunted in 2016 paid $25.6 billion to participate in their sport, down from 13.7 million hunters who spent $36.3 billion in 2011, according to that same USFWS report. That’s a significant decrease of 29 percent. Despite the drop in participation and expenditures that include sporting equipment, there is good news.

“We don’t think it’s time to panic yet, or walk back more than a century of commitment to conservation by hunters,” says Mike Leahy, senior manager of public lands conservation and sportsmen policy at the National Wildlife Federation. “While hunting participation has declined, and a lot of hunters are getting older, there are a lot of positive signs, from interest in hunting from a wide range of outdoor enthusiasts to classes that fill up early for hunter education, youth archery, and shooting sports.”

Leahy thinks hunting and shooting may never be as popular as they once were, but enough people enjoy these activities—and will continue to do so—to sustain the sports and their contributions to conservation.

P-R Funds in Flux

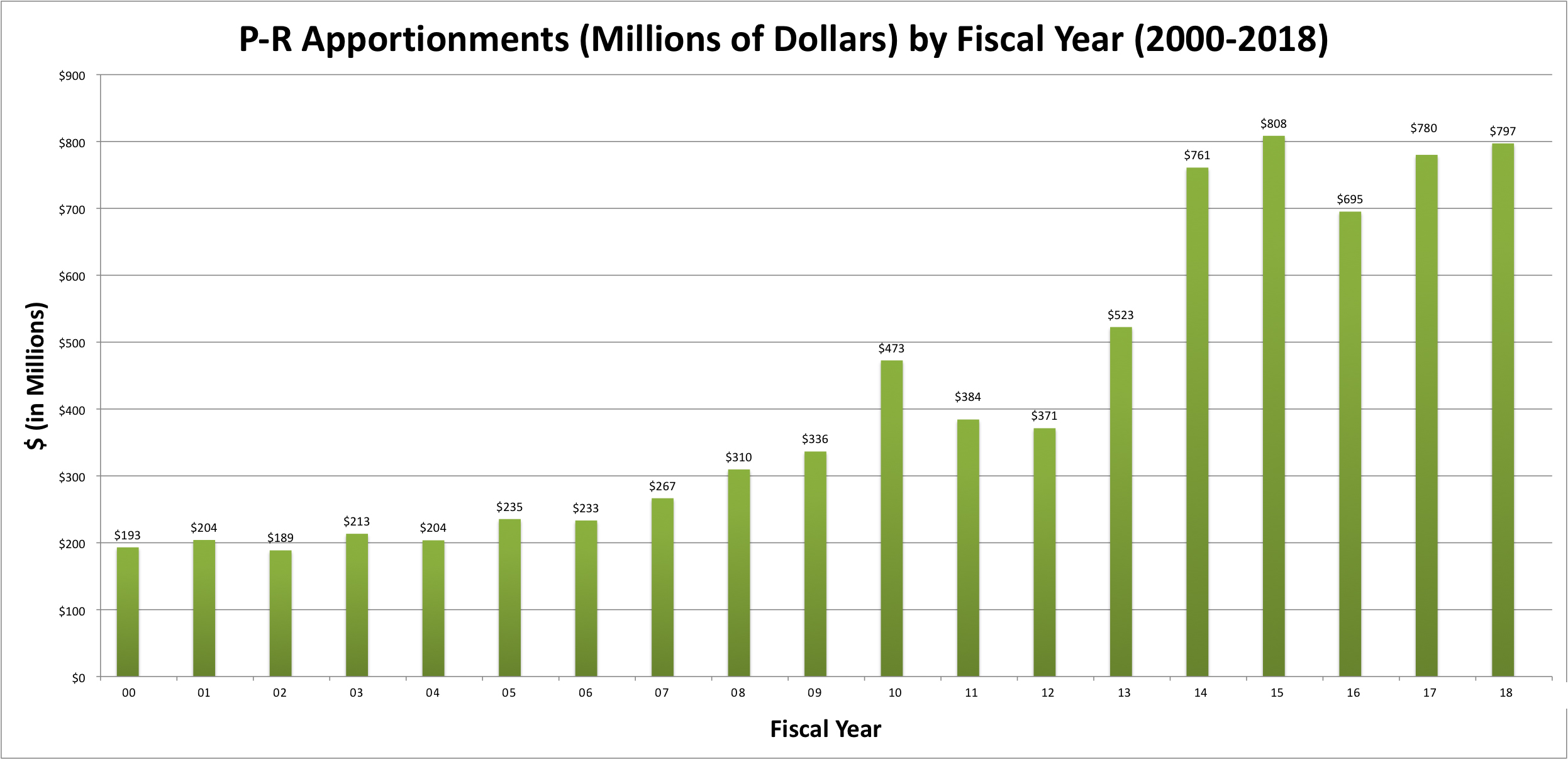

Despite the continued decline of hunters, there’s more P-R money than there was a generation ago. The $797.16 million allocation in 2018 is $17 million more than the previous year’s apportionment and more than twice as much as the annual allocation in 2012. It is actually the second-highest single-year allocation ever—about $11 million less than the $808.5 million apportioned in 2015.

Some experts caution though that the ‘Obama Bump’ in gun sales—not hunting—fueled the P-R’s recent spike. With the ‘Trump Slump’ slowing firearms sales, they fear a dramatic tail-off in allocated funds is inevitable.

Other industry experts say an improving economy will spur more spending on recreational activities, including hunting and shooting, which will sustain steady P-R funding.

The ‘Obama Bump’ in gun sales coincided with tougher economic times for states in declining license and fee revenues, says Bronson of Vista Outdoor. With better economic times, state-generated funds should increase, supplanting any potential decline in federal contributions. Even if P-R revenues decline, he points out, it won’t be a precipitous dropping off, but a new plateau.

Idaho Fish and Game Director Virgil Moore, who is also the president of the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies, says when P-R revenues tripled in less than a decade, peaking in 2015, state wildlife agencies took a conservative approach in how they allocated the boost.

“We don’t know what the future is. It was used for one-time projects,” he says, citing examples such as a $300,000 grant for graduate students to assist in field surveys and data collection. “If the money is going away, we don’t have to fund [those one-time projects] anymore.”

Three Bills to Boost Hunting

The decline in hunter participation is fostering proposed innovations that could, potentially, change P-R funding emphasis from conserving game animals to saving hunters.

“Investing in shooting space will be a big trend,” says Nick Wiley, chief conservation officer for Ducks Unlimited, and former executive director of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “We don’t want to lose sight [of wildlife funding], but we must be mindful that money needs to be spent to sustain the sport that sustains the fund.”

“[The goal is to] improve and build more shooting ranges,” Moore says. “This is where the money comes from.”

Meanwhile, Crane has a different perspective.

“Top priority? Right now, one word: Access,” he says. “The goal is to use P-R funds to increase access to places where people can hunt and shoot.”

Three bills currently making their way through Congress would dedicate more money directly, and indirectly, to hunting and shooting sports. They are:

1. HR 788, The Target Practice and Marksmanship Training Support Act

Sponsored by Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-North Carolina, this would allow P-R funds to pay up to 90 percent, rather than 75 percent, of costs in acquiring land for expanding, or constructing, public shooting ranges. It’s been in the House Subcommittee on Constitution and Civil Justice since March 2017.

By lowering the P-R match to 10 percent, it gives states more ability to award grants for shooting ranges and hunter ed programming.

State agencies can form public-private ventures to enhance public access, so a privately-owned shooting range could qualify for a grant if its proposal met certain public-access criteria, IDFG’s Moore said.

“As I review budget requests, I’m looking for bang for my buck,” he said, noting grant applications are more likely to receive IDFG approval if they involve coalitions offering multiple benefits.

2. HR 2591, The Modernizing The Pittman-Robertson Fund For Tomorrow’s Needs Act of 2017

Sponsored by Rep. Austin Scott, R-Georgia, this legislation would authorize P-R funds to recruit, retain, and reactivate hunters and recreational shooters. It’s been in the House Natural Resources Committee since February.

Crane said P-R funds would complement marketing campaigns by the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF). “They have good programs and want to capitalize on this,” he said.

Allocating P-R funds for marketing is fine if money for wildlife restoration remains intact, NWF’s Leahy said.

“We think those ought to start small, by redirecting some money from hunter education to marketing, until we know more about how effective these ideas are, how much they cost, and how great the need is,” he said. “Let’s see what the return on investment is before we start pulling money from wildlife biologists and habitat managers.”

3. HR 4647, The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act

Sponsored by Rep. Jeff Fortenberry, R-Nebraska, this would redirect $1.3 billion in existing royalties and fees annually from drilling and mining on federal lands and waters to conserve “the full array of fish and wildlife.” It’s also been in the House Natural Resources Committee since February.

The bill would “intermingle” P-R funds with, potentially, $1.3 billion earmarked to “provide more money for species that don’t have stable funding,” Moore said.

This will indirectly benefit hunters who ideally want P-R allocations dedicated to game animals, Leahy said, because habitat is habitat. HR 4647 “would get states the money they need for wildlife” using little P-R money, he said.

This impacts hunters because a non-game animal can still be designated endangered—such as the timber rattler in New York’s Hudson Highlands—thereby imposing restrictions on hunting lands.

HR 4647’s goal is to “keep species from becoming endangered” and avoid access restrictions, DU’s Wiley said. “Restricting access is rarely a good thing. It’s all about the habitat.”

Expanding the Excise Tax?

Some experts think it’s time to expand P-R taxes to more hunting- and shooting-related products.

Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Teddy Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, thinks hunters should lobby to get items such as treestands, reloading equipment, powder, and primers included in P-R to increase the revenues that give them leverage in influencing conservation policy.

“Take a walk on the floor of the SHOT Show,” he says. “A great majority of that stuff is exempt from Pittman-Robertson.”

Still, he won’t be looking outside the hook-and-bullet community to step up. Fosburgh thinks expanding the tax beyond hunting- and shooting-related items would dilute priorities and direction in game and land management.

But Vista’s Bronson and NWF’s Leahy don’t think such an expansion would diminish hunting or hunters’ efficacy. Bronson says extending the P-R tax to “outdoor products you can buy at REI— bicycles, camping gear, tents—following that P-R model” would benefit all, especially wildlife.

Leahy says “a blue-ribbon panel we are part of” has been aggressively campaigning for an excise tax on all outdoor gear. But, he admits, “We’d never get it through Congress.”

The fact that hunters, shooters, and anglers willingly pay a substantial tax for wildlife habitat has, as Kovarovics puts it, provided “an awareness and sense of pride” among our community.

Beyond individual projects, there is, he says, “A broad policy benefit that flows from this as sportsmen fund conservation in the taxes they pay to restore habitat that people can enjoy [whether they are hunters or not].”

Read Next: Why We Suck at Recruiting New Hunters, Why It Matters, and How You Can Fix It

The benefits should be spelled out more clearly and shouted out more loudly, according to Fosburgh, who says advocates have done “a terrible job” of promoting the P-R tax’s value.

“Honestly, I sometimes think hunters need to become more knowledgeable and better ambassadors of their role and contribution,” Crane says. “No one else puts their money where their mouth is like hunters and anglers do. You are one of the greatest conservationists by carrying your firearm and fishing rod.”

“It’s a hell of a great story,” he adds. “I don’t know if we tell it very well.”