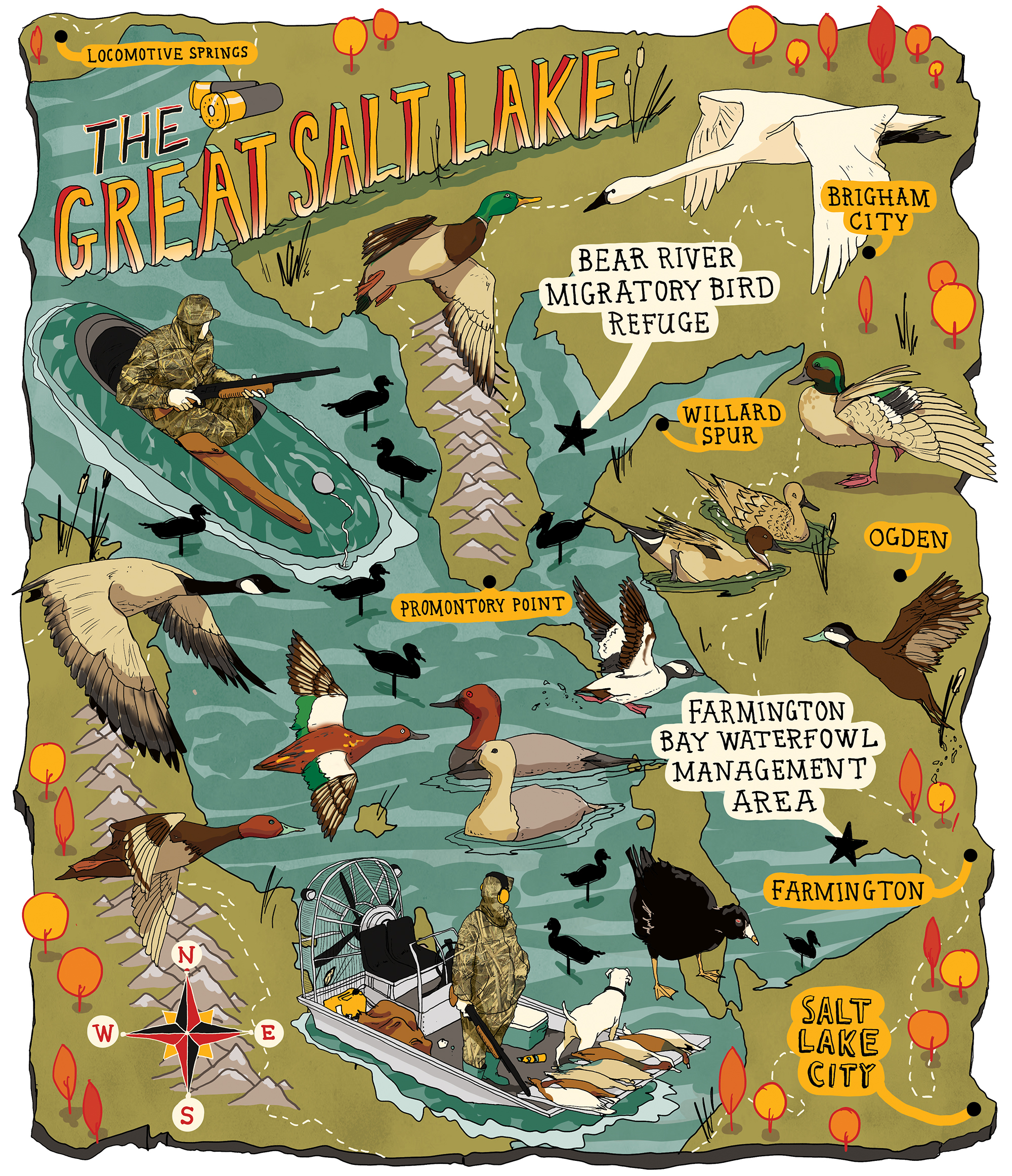

The appeal of the 75-mile-long Great Salt Lake is almost as powerful for waterfowl hunters as it is for birds. The lake has good public access, habitat that enables a wide variety of hunting styles, and extensive marshland that attracts a diversity of waterfowl species unrivaled elsewhere in the flyway—and probably the continent.

I hunted the GSL last November in two very different ways. I rode an airboat into the remote interior of the lake, spread out hundreds of decoys, and shot dabbling ducks in a wilderness of alkali bulrush. Then I hunted diving ducks from a simple layout boat anchored in the open middle of Farmington Bay, a popular public marsh close enough to downtown Salt Lake City that I could hear garbage trucks rumbling on the city’s streets.

Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge Nov. 10, 2015 We tow airboats in the dark down the main street of Brigham City, We’re headed for Willard Spur, a causeway that extends across the marshland of the Bear River Delta, where we’ll launch the boats. The Bear is the largest freshwater tributary to the lake, and the brackish water that extends from its mouth out into the lake is among the best waterfowl habitat on the Great Salt Lake.

Nearly the entire delta is managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service for waterfowl production and public hunting. The 74,000-acre Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge is the airboat was invented back in the 1940s. Biologists needed shallow-drafting boats to help them assess duck populations and habitat, and the flat-hulled craft, pushed by giant, rear-facing propellers, were the answer.

They still are for waterfowl hunters who want to access the vast interior of the lake. Here’s the thing about the Great Salt Lake: Its water is only a few inches deep in many places, too shallow for V-hulled boats. But its alkali mud is so deep and boot-sucking that walking across shallow bays is impossible.

Airboats enable hunters to reach the thousands of acres of brine flats on the Bear River Refuge and westward, out toward the vast lake leading to Promontory Point.

I’m hunting with Chad Yamane of Fried Feathers Outfitters (https://www.friedfeathers.com/), who motors his boat for 20 minutes, navigating a maze of house-high phragmite reeds and acres of same-looking bulrush. Finally, he finds a spot to stake out hundreds of thin silhouette decoys, and we settle into our layout blinds in the tall reeds. Over the next hours, we dupe a few mallards, a pintail, and a mess of greenwing teal. We’re not quite limited out when we pull up stakes. Rough weather is headed in, and we return to Willard Spur.

For all their ability to access thousands of acres of unpressured habitat, airboats have their limitations. The spot we picked, based on the northwest wind of the morning, isn’t as good when the wind shifts out of the south. But it would take so much time and work to reset our decoy spread that we settle for a few singles and doubles every hour or so. The next day, the group that rides airboats to this same spot limits on greenwing teal and mallards in about an hour. Yamane described the funnel of birds that dropped into their decoys as “cyclonic.”

Farmington Bay Waterfowl Management Area Nov. 11, 2015

If riding an airboat seems like NASCAR—the boats are fast and so loud you have to wear earmuffs—then hunting out of a layout boat feels like resting in a hammock. A cold, hard hammock, to be sure, but the rocking of the boat on the water is so peaceful, I nearly drift off to sleep.

Then shooting light arrives, and the gunfire all around me snaps me alert. I’m on my back in a tiny boat in the very middle of Farmington Bay, one of the most popular waterfowl areas on the lake. I get buzzed by one, then a half dozen flocks of ducks. They’re easily within shotgun range, but it’s too dark to positively identify them.

As the light rises, I can ID the birds—they’re a mix of redheads and ruddy ducks—but I miss so badly on my first volleys that I wonder if my barrel is bent. I’m shooting several feet behind the streaking birds. The divers fly much faster than mallards do, but because of my position, I can’t get my gun up and swinging fast enough.

That’s one of the challenges of layout boats. The boats, which were designed for hunting the open water off the Atlantic Coast, sit low in the water in the center of blocks of decoys. In order not to stick up and spook birds, hunters lie flat on their back, sitting up and making quick shots when birds fly in range. Layout boat hunting has caught on here on the Great Salt Lake, where the shoreline is full of pass-shooters, but relatively few hunters access the open water. My boat, a 9 ½-foot molded-fiberglass model called the Reaper, is made right here in Utah by Backwater Performance Systems.

It takes me a few misses before I realize I have more time than I expected. As long as I can spot incoming birds and positively identify them, I can pick the one I want and make the shot. As long as I keep my barrel moving, that is. When my form falls apart and I neglect to follow-through, I miss.

The trick to layout boat hunting is to have a tender ship. In this case, it’s piloted by my friends Matt Anderson and Jeff Bringhurst. The pair hangs out on shore, watching me through a spotting scope (and eating a hearty breakfast). When they see I have a few birds down, they motor out, scoop up ducks with a net, refill my coffee cup, and reposition the decoys.

After two hours, I am one bird short of a remarkable mixed bag: a fully plumed wigeon drake, a bull pintail, a hen gadwall, a drake ruddy duck, and a bufflehead. I’m holding out for a canvasback, the trophy duck of any layout gunner. But when a second drake pintail flies in range, I can’t resist. I’m done, and ready for breakfast myself.

I’m a convert to layout boat hunting, at least in the right conditions. The waves can’t be too tall or they’ll swamp the boat. And there have to be enough birds to provide steady action. Lying on your back all day in a cold November lake with no shooting could easily turn a hunter off this style of waterfowling.

As we drive out of the Farmington Bay WMA, I see what keeps the birds around. Nearly half the public marsh is set aside as a rest area, where hunting isn’t allowed. I see tens of thousands of birds, a mix of dabblers and divers, several hundred snow-white tundra swans, and dozens of rusty-headed canvasbacks—all feeding and chuckling, enjoying themselves on the Great Salt Lake before continuing their journey south.