COMING OUT OF the stern waves, the first big one raced along the surface after the starboard teaser, his fin and tail cutting through the top of the water. The marlin’s long, narrow, purple side fins were extended like the wings of a bird, and his sword almost touched the teaser as he charged, even though Carlos had the boat going full speed and we were pulling in the teasers as fast as we could.

The marlin followed the teasers right up to the boat and, when we pulled them out of the water, he kept on coming until his bill was within an inch of the stern. He seemed to think the teasers were bonito and had taken refuge under the boat and might have gone on into the propeller had not Ernest Hemingway reeled in and dropped a piece of bait on his bill. Immediately the spear leaped two feet out of the water, and the marlin slashed at the cero mackerel. Hemingway, seeing the bait was well in the fish’s mouth, struck without slacking.

Zing! There was a shrill cry of gears, straining against a terrific burst of speed, and the line went tearing off the spool, forcing the rod down until its tip almost touched the water.

Ten feet behind us he jumped straight up, 250 pounds of striped marlin, with wet sides glistening silver in the late afternoon sun, and the stripes along his dark back and melting into the flashing white of his belly. He danced on his tail and looked us over. Then he went down again, turned a few lightninglike somersaults in the air, and began to jump with his mouth open wide, shaking his bill in an attempt to throw the hook.

Six times he cleared the water. Then, fighting deep, he went off like a torpedo, taking out line in long jerks, with the rod snapping back and forth like a whip. Hemingway, sitting in the swivel chair, his feet braced solidly on the fish box, screwed down the drag and pressed the palm of his hand against the revolving spool until the bending rod and line had all the tension they could stand. The line was running into the purple water toward Havana, and the boat was headed Northwest.

“TURN AROUND!” Hemingway shouted to Carlos at the wheel. “Head southeast for Cojimar!”

Carlos, new to the wheel of a motor boat, did not turn around but kept the Pilar headed northwest. The marlin came up 300 yards astern, running toward Cojimar in a succession of long, surface jumps, with the boat going ten miles an hour in the opposite direction!

“Swing the boat around!” Hemingway repeated in Spanish. “Follow the fish!”

This marlin, an exception, was running toward shore, and Carlos had believed that he would head out into deep water, as big ones usually do. Now, at Hemingway’s command, he swung around.

With nearly 500 yards of 36-thread line out and the boat being handled poorly, odds were in the marlin’s favor. Hemingway put his harness on and hooked it to the reel.

All afternoon the wind had been increasing from the northeast, kicking up a heavy sea against the current of the Gulf Stream. The boat tossed and rocked, cutting sidewise through the waves, headed a few degrees to the left of the fish. The sun, already dropping, would soon set. Hemingway worked the line in fast, raising the rod with both hands, his thumb tight against the line to prevent it from going out. Pulling with all the force the rod and line would stand in the heavy sea, he reeled quickly whenever his side of the boat dipped.

After half an hour, the boat passed the marlin and Hemingway worked him in from astern, with the boat moving slowly ahead. Just after the sun set, we saw the knot come out of the water and soon Hemingway had a few yards of the double line back on the reel. The marlin was near the surface, but it was too dark to see him.

Then, to our dismay, a pair of large sharks came up, swimming slow circles around the line. Carlos threw bait to them but they would not strike. The marlin, frightened by the sharks, sounded.

“Bring me the Mannlicher,” commanded Hemingway. Holding his fishing rod in one hand and the rifle in the other, he shot, but the sharks were not close enough to kill. He succeeded merely in driving them off.

He danced on his tail and looked us over. Then he went down again, turned a few lightninglike somersaults in the air, and began to jump with his mouth open wide, shaking his bill in an attempt to throw the hook.

Hemingway, returning to his chair, suddenly cursed, and then reeled in quietly. The double line had been cut close to the leader swivel by the sharks. There was not much talk as we ran back that night to Havana.

A few days later, we were out again, this time in a lumpy sea. My bait was passing through a swell, out of sight, and I was holding my rod with one hand, the finger tips of the other touching the free spool of the reel, ready to let it out if anything should strike. Something did strike and nearly jerked the rod out of my hands. Instead of letting the line go, I got excited, screwed down the drag and struck back, pulling the smashed bait out of the fish’s mouth. In another second we saw a bill come out of the water and Hemingway had a smashing strike.

“Shut her off!” he shouted to Carlos. Hemingway stood up between his chair and the fish box, feet wide apart, and pointed the rod at the fish so the line would go out freely. Pressing his finger tips lightly against the spinning spool to prevent a backlash, he let out fifty yards of line.

“Put her ahead!” he ordered Carlos. Screwing down on the drag, Hemingway’s rod came back horizontally on the starboard side in three long, hard strikes, but the fish had dropped the bait. While Hemingway was reeling in fast, the fish struck again. He unscrewed the drag and again slacked. This time the line was alive and jerked off the reel. When he struck, the rod bent double.

THE HUGE MARLIN broke through a swell fifty yards astern. He shot upward, stiff as a ramrod, blue on top and silver below, the two colors divided sharply by a line down his body, sword pointed up at the northwestern sky, the tail plowing up a tremendous white spray. When finally he cleared the water he left behind two sheets of spray, spread out in the air like the wings of a bird in flight. Then he came down tail first, merely touching the water, and shot up again, to stand motionless against the lighter blue of the horizon. After another leap he dived and darted off against the current to the northwest where the water was 700 fathoms deep.

By this time a line fished by a guest had become wound around Hemingway’s line. I disentangled the lines and Hemingway began to work on the fish while the rest of us hauled in the teasers. Carlos turned the wheel over to Juan, the cook, who had learned to handle the boat fairly well, and the Pilar headed northwest, running parallel with the marlin, with Hemingway working on the dragging belly of the line.

Again the marlin came up through his own white spray, much farther away than at first, and six times stiffly jumped clear. Then he fought deep.

With the drag screwed down tight, Hemingway gripped the spool with his fingers, bearing down hard. The running line began to slow down and at last the spool stopped. The marlin had been turned in his run.

“If you can hold them, you can always get line on them,” Hemingway had often said. To prove it now, he gripped the rod above the reel with both hands, pressed his thumbs tightly against the line, and brought the rod up slowly, reeling in as he lowered it. While doing this he worked the fish hard, to prevent him from starting another run.

The boat made a semicircle ahead of the fish, moving slowly so Hemingway could bring him up to the surface. In a few minutes we saw the marlin, looking like a submarine about to ram our stern.

Juan was doing well at the wheel. When Hemingway had the fish almost under the stern, deep down, he would tell Juan to give the boat a little more gas, and, as the boat moved ahead, the fish would fall back a little, coming nearer the surface. Then Juan would cut down the motor and Hemingway would work the fish close again, still too deep to gaff. This was repeated several times.

At the end of thirty minutes the fish came up, his fin and tail out, and Hemingway worked him alongside the stern. Carlos, with gaff ready, leaned over the side and struck the fish in the side. The marlin, with a mighty lunge, broke away, splashing water over us and carrying off the gaff. Two market fishermen, standing by to watch the battle, retrieved the gaff.

The marlin tried to sound, but Hemingway soon stopped him and played him on a short line. The forward movement of the boat kept him from getting his head down. Hemingway had the leader out of water six times but was unable to raise the fish.

While this tug-of-war was going on a large shark struck the marlin in the flank, and the latter rocketed to the surface in three long jumps with the shark following; he began to pull in circles, fighting as hard as ever.

Seeing that the marlin wanted to go with the current, Hemingway had Juan swing the boat around. Remembering the marlin of which sharks had so recently robbed him, he kept working the fish rapidly. Finally, the fish was thoroughly beaten and came up, floating like a log, belly up. Hemingway led him to the stern. The fight had lasted an hour and fifteen minutes.

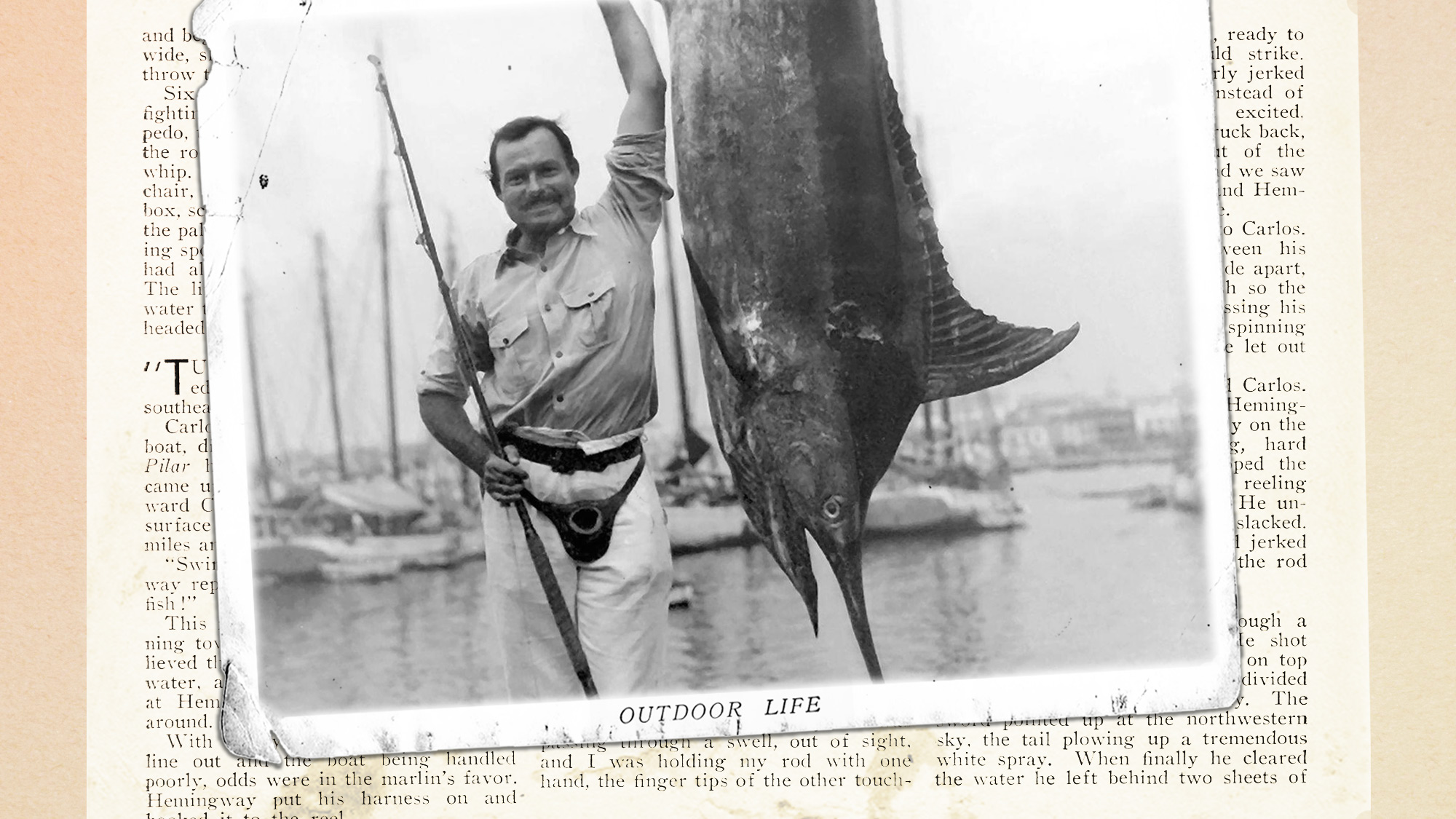

That evening, in a drizzling rain, we ran in at Casa Blanca, the small town underneath the Cabanas fortress across the harbor from Havana, where about fifty naked kids and half-naked men gathered to see the fish and to help pull him up on the dock. With the marlin hanging from a scaffold, we took a picture with Havana as a background.

From the tip of his bill to the end of his tail the marlin measured twelve feet, two inches. His girth was four feet, eight inches, and weighed 420 pounds.

After that first heart-breaking battle with the sharks, it was some satisfaction to find that this marlin was almost twice as big as the one we had lost.

This story, Beating Sharks to Marlin, originally ran in the June 1935 issue of Outdoor Life. Ernest Hemingway also contributed several opinion pieces to Outdoor Life in the 1930s. Read more OL+ stories.