We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Ask any enthusiastic hunter under age 30 what piece of gear they’re saving their money to buy, and I’ll bet the majority will tell you it’s a thermal scope. Or maybe a thermal monocular.

Thermal devices, which use a particular lens element called germanium to detect subtle variations in temperature, and then employ digital sensors and displays to render images of the world that’s defined by heat, have been around for over 50 years (re-watch the 1987 Arnold Schwarzenegger movie Predator to see the first thermal images in popular culture). Because of their expense (high) and availability (low), thermals have been primarily reserved for military use — helicopters, tanks, drones, and most infantry helmets and weapons are equipped with a thermal device, which are used for everything from identifying and engaging enemy combatants to detecting land mines and finding lost soldiers. Thermals, sometimes called long-wave infrared detectors, have made their way into domestic police forces, too. They were famously used to locate the 2013 Boston Marathon bomber, and more recently to find a Pennsylvania fugitive. They’re also been used effectively by firefighters to see through the dense smoke of burning buildings, by search-and-rescue teams to find lost hikers and boaters, and by electrical utilities to detect power leaks and overheating transformers.

Thermals haven’t been widely adopted for hunting situations for a couple sensible reasons. First, because it’s widely illegal to hunt at night. Second, because they’re expensive. Field-grade thermals routinely cost $5,000 and more. Night-vision devices, which amplify ambient light rather than detect temperature variations, are even pricier.

Consumer-grade thermals have, for the past 20 years, been confined mainly to Texas, where they’re mighty effective for gunning hogs and coyotes at night, and to Europe, where hunters are much less price-conscious of their gear, and where there’s no legal prohibition on hunting game animals at night.

But as with so many devices, from cell phones to trail cameras, thermal devices have gotten more capable, and less expensive as technology has fueled what I’d call an access evolution. Suddenly, thermals are more affordable and ubiquitous, and American hunters are hungry for additional ways to use them.

The Rise of Thermals for Hunting

In elk, deer, and even waterfowl camps around the country over the past couple years, young guides and hunters have either shown me their newly purchased thermals, or they’ve quizzed me on the models they should buy. The energy around thermals reminds me of consumer interest in ARs 20 years ago, when everybody either had just bought one that they were experimenting with, or they were spec-ing out the model they should buy or build. Companies like Daniel Defense, Luth, and DPMS couldn’t build civilian ARs fast enough, and in the years that followed, the surge similarly boosted the AR accessory market.

Five years ago, thermals were novel outside Texas. There were a few early efforts to penetrate the consumer market (Seek Thermal’s smart-phone camera and Leupold’s discontinued LTO Tracker among them) but most civilian thermals were either too expensive or too slow, cumbersome, and obtuse to deploy effectively in the field. Sightmark, the Texas company that imports Pulsar thermals from central Europe, Teledyne FLIR, and ATN have been on the frontier of bringing affordable, competent thermal rifle scopes to American hunters, while European brands like Zeiss and Leica have led the way with high-end thermal monoculars and clip-ons, which convert a traditional rifle scope into a thermal detector. Check out Zeiss’s excellent explainer of thermal technology here.

While thermal technology, especially the digital processing that turns smudgy suggestions of a distant coyote into a sharp, recognizable image, is evolving quickly, the most meaningful change to thermals is their price. A dedicated thermal riflescope that might have cost $5,000 a couple years ago is now priced under $2,000. Similarly, hand-held thermal monoculars can be found for the same price, and if you want to plug a small thermal camera into your smartphone, you can pick one up for between $200 and $400. I should note, though, that cheap thermals are maddening because of their poor resolution, slow refresh rates that freeze images for seconds at a time, and woefully short battery life, especially in cold weather. If you want the best thermal experience, save up for top-of-the-line models.

At this year’s SHOT Show, the hottest gear category was thermals, and I counted at least a dozen new companies, some hawking knock-off Asian thermals, others introducing new units with vastly greater imaging capabilities than their previous models. I saw vehicle-mounted thermals from InfiRay, which also introduced an ultra-high-definition thermal riflescope, a dual thermal/night-vision binocular from Pulsar, and a very good $700 monocular from FLIR.

“I feel like this industry has the energy, optimism, and momentum that people must have felt at Apple when it came out with its first iPhone,” says Michelle Gandola, who runs marketing and PR for Sionyx, a company that specializes mainly in night-vision equipment. She’s talking about the pace of innovation in both thermal and night-vision segments, the number and variety of applications that the technology is informing and improving, and the sheer market penetration the category is enjoying, and in some cases creating.

Matt Farris, product line manager for iRayUSA, distributor of InfiRay thermals, said he expects thermal resolution to double every year for the foreseeable future, as digital technology becomes better and cheaper.

Are Thermals Legal for Hunting?

The availability and accessibility of thermals is pushing the limits on their use. Remember those young hunting guides who had thermals in their pickups? They often use them to scan the landscape to scout for animals. Others said they invested in thermals in order to more effectively pursue and find wounded game, mainly at night.

Both those activities are illegal in most states, where thermal use is limited mainly to hunting non-game species like coyotes, possums, and feral hogs. Some states prohibit the use of night-vision and thermals on public land, and in other states it’s illegal to have thermal devices in your possession while hunting game animals. Here’s a rundown of each state’s rules governing thermal and night-vision use, though I should note that I haven’t fact-checked these details. Sightmark has published a similar state-by-state roundup of thermal legality. (If you intend to use thermals for any hunting-related purposes, make sure to check your local regulations).

In my home state of Montana, where I’ve been field-testing thermals for the past two years, I’ve been cautious about using or even possessing them during big-game hunting seasons. That’s because of the state’s blanket prohibition on the use of “artificial light” to take game animals. Thermals and night-vision (along with spotlights) are considered artificial light.

Even retrieval of game animals is problematic with thermals. It’s a topic I put to my local Montana game warden, Todd Tryan, who says he’s encountering more and more hunters with thermals in the field.

“Let’s say you use a thermal to aid in the recovery of an animal,” he noted. “You find it, and it’s not dead. If you put it down, you are now in violation of using artificial light in pursuit of an animal. If you don’t put it down, you might not be in violation of the law, but I’d argue you’re in violation of basic hunting ethics. In my experience, the fair-chase aspect of hunting goes out the window as soon as you bring out these thermals.”

With technology as disruptive as thermals, it’s easy to imagine problems that may not exist, and some of the existing problems are resolvable by enforcement of existing laws. But we have a fairly established technology in another aspect of field sports that may provide some insights into the turbulent effect of a new category of gear: forward-facing sonar (FFS) in recreational fishing.

Are Thermals Cheating?

Some have called for FFS technology to be banned because it’s so effective at helping anglers find and catch open-water sport fish. Others have called for voluntary limitations on its use. But as Outdoor Life fishing editor Joe Cermele has argued, there’s no stopping the advance of technology like forward-facing sonar.

“The likelihood of us going backward — agreeing that modern tech could be so harmful that we have to try to stop trying to make it better — is extremely unlikely,” Cermele wrote. “Nothing in our lives is immune to technological one-upmanship, and fishing is no exception.”

Neither is hunting, which is why thermal technology is potentially so disruptive. Unlike fishing, in which a caught fish can be returned to the water, successful hunting results in a dead animal, and the more effective thermals make hunters, the more impact we may have on wildlife populations and behaviors. For many hunters, satisfaction is derived from a number of elements, including solitude. But widespread deployment of thermals (and to a lesser degree, night-vision), risks congregating hunters where the animals are.

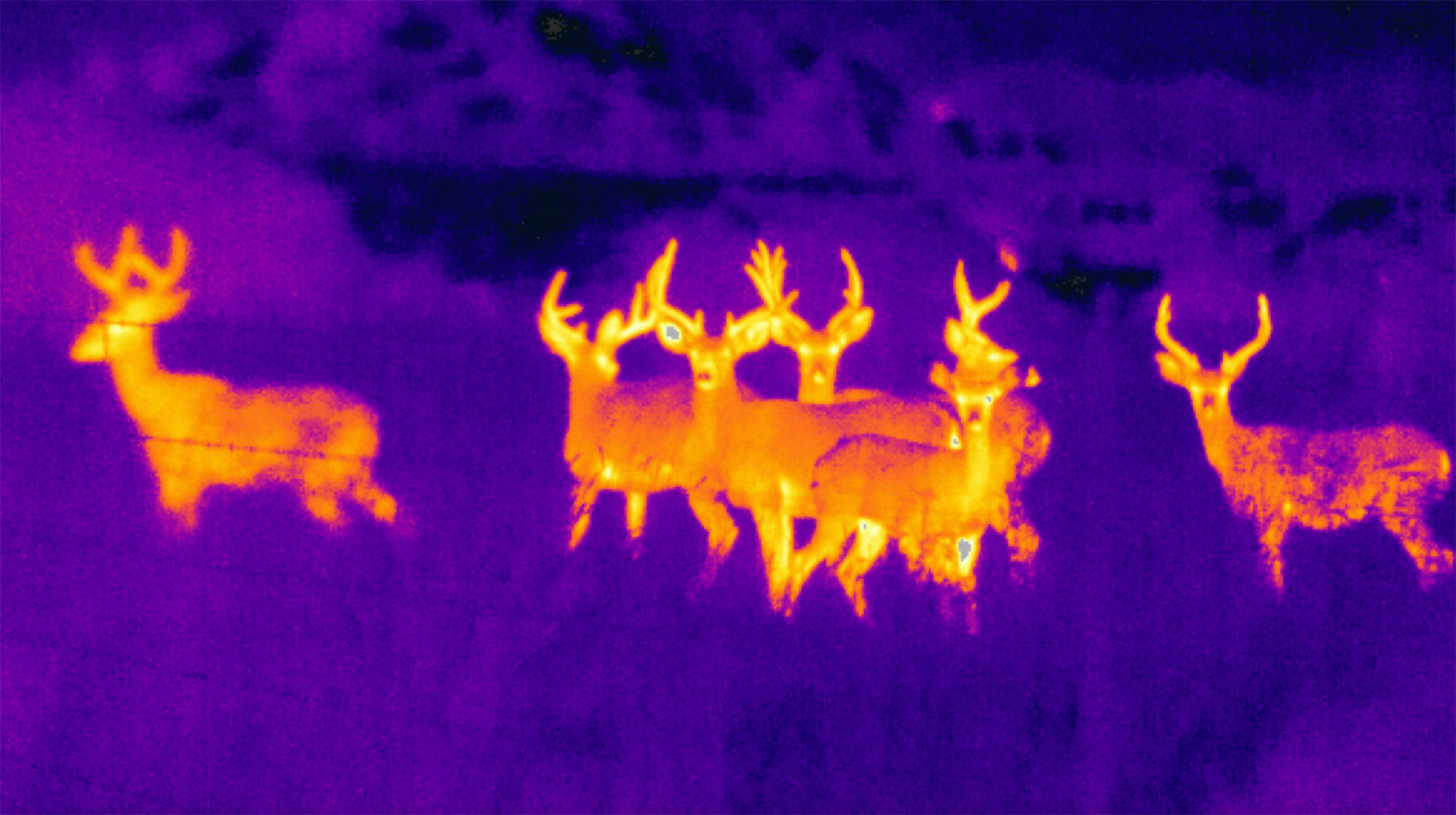

Imagine rolling into a timbered basin (in daylight or night), and scanning the terrain, looking for telltale thermal signatures tucked into the trees. We’re only a year or two away from very sharp sensor and display resolution, to the degree that users will be able to differentiate an elk from a mule deer, or a cow elk from a bull. Those with this technology will have an important edge on those without that technology, who would be consigned to using their legs, traditional optics, and understanding of animal behaviors, to find game. The thermal users would be able to short-cut much of that work and cover far more ground, much faster.

This mimics what’s happening in fishing, with success determined by the haves (those with forward-facing sonar and the expertise to use it) and the have-nots, those hapless suckers without the technology.

If you accept that thermal technology can make hunters more effective, then it might not be prohibitions on the devices that govern our use of them. It might mean restrictions on participation. This is already happening in elk units where harvest rates have increased because of hunters’ effectiveness, whether it’s because they’re killing animals at longer distances, buying better gear to push deeper into the mountains, or using mapping technology to find previously hidden access to herds. Game managers have responded by issuing fewer tags or shortening seasons, all of which rankles hunters who often don’t recognize their own behavior as a reason for the restrictions.

In addition to voluntary restrictions, you can expect to see further legal limits on the use of thermals. We actually have fresh examples of legal responses to technology. Last year, Utah banned trail cameras on public land during hunting seasons, largely because unregulated cameras were leading to hunter conflict and crowding and altering distribution patterns of wildlife. In 2022, Arizona banned all trail cameras for hunting. Even more to the point of thermals, Utah last year prohibited “the use of any night-vision [this includes thermals] device to locate or attempt to locate a big game animal between July 31 and Jan. 31.”

Will bans or legal restrictions slow the progress of thermal technology? It’s unlikely. Already brands are talking about incorporating artificial intelligence in their thermal sensors, in order to better identify targets, and adding geo-location and mapping overlays to thermal-derived videos and images. You can expect to see the first thermal trail cameras later this year.

Here’s what we know from previous technological revolutions in the hunting space: Competition between brands will accelerate the pace of technology. Consumer prices will drop. Selection will increase. Plus, there’s a good chance the night-vision industry will become active in the legislative arena, lobbying to either preserve existing allowances or expand use of thermals and night-vision devices. If you need an example of the power of special-product lobbying, look no further than the crossbow industry, whose lobbying over the past 10 years has expanded crossbow use in archery seasons in 35 states.

It’s worth considering that, as we fill the available landscapes with hunters and spend more of our time and resources figuring out how to be more effective hunters, there’s one frontier that’s still relatively undiscovered: nighttime. And thermals and night-vision technology are poised to do for nighttime users what traditional optics have always done for daylight users: to allow us to better understand and enjoy the world around us. Of course, I could also make the case that wild animals deserve the relief from hunters that nighttime provides.

All of this comes back to a practical question to consider as you think about how cool it would be to join the thermal club: Just how do you intend to use the technology?

The forward-facing sonar controversy from the fishing world offers some guidance. In Cermele’s article, bass pro Randy Blaukat noted that the technology is making practitioners of it worse fishermen.

“It takes away from the mystery and magic of fishing,” Blaukat said. “Which once you do that, once you take away the unknown from fishing, you lose everything that fishing’s about.”

Replace “fishing” with “hunting,” and you have a good notion of what’s at risk of being lost with the widespread adoption of night-vision and thermal technology in the field.