We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Of the hundreds of commercial metallic cartridges introduced, the .270 Winchester is one of few that have maintained a century-long tenure of popularity. As a youngster, I remember hearing my first real cartridge debate at the local gun store counter — a couple of hunters hashing out the merits of the .270 Winchester versus those of the .30/06 Springfield. That was after both had been around for over 75 years!

That the .270 Winchester has remained one of America’s most popular big game cartridges for a hundred years lends credit to its effectiveness in the field. It was a sweetheart of hard-hunting gun writers like Jack O’Connor, and favored for its flat trajectory and mild recoil. Though it was often underestimated, the cartridge rivals the performance of some popular magnums. There are ways that modern cartridges have been improved, but the .270 Winchester can still hold its own. Here’s everything you need to know about this classic big game cartridge.

.270 Winchester Specs

- Parent Case: .30/06 Springfield

- Bullet Diameter: .277 inches

- Max Cartridge Overall Length: 3.340 inches

- Case Length: 2.540 inches

- Bullet Weights: 100 to 175 grains

- Year Developed: 1923 (Introduced in 1925)

The .270 Winchester Was a Wildcat

A sure recipe for commercial success of a cartridge in the United States is for the military to adopt it. The .30/06 Springfield, .308 Winchester, and 5.56mm NATO are all good examples of this. The .270 Winchester is derived from the .30/06 case, but it was never a military cartridge. It was designed in 1923 and presented by Winchester in 1925 as the .270 W.C.F.

The cartridge is simply a necked-down .30/06 with a lengthened neck and shoulder. Dimensions to the base of the shoulder are identical, and some of the same powders are suitable for both cartridges. The introduction of the .250-3000 Savage for the model 99 in 1915, which was also a derivative of the .30/06 case, was celebrated by hunters who recognized the value of a cartridge that was light-recoiling and had a flat trajectory. Its claim to fame was breaking 3,000 feet-per-second with an 87-grain bullet. It was quickly snatched up by market hunters like Frank Glaser in Alaska — who used his to kill many Dall sheep and at least one cranky grizzly bear.

The .270 W.C.F. produced even more impressive velocities while firing heavier 130-grain bullets. Sporting optics were still in their infancy, and a cartridge that didn’t present a rainbow-like flight path was lightning in a bottle. It’s no surprise that writers like Col. Townsend Whelen took an immediate shine to it. He later said the following about the .270 Winchester: “I think it is our best American big game cartridge in the hands of a rifleman who can avail himself of its flat trajectory and fine accuracy.”

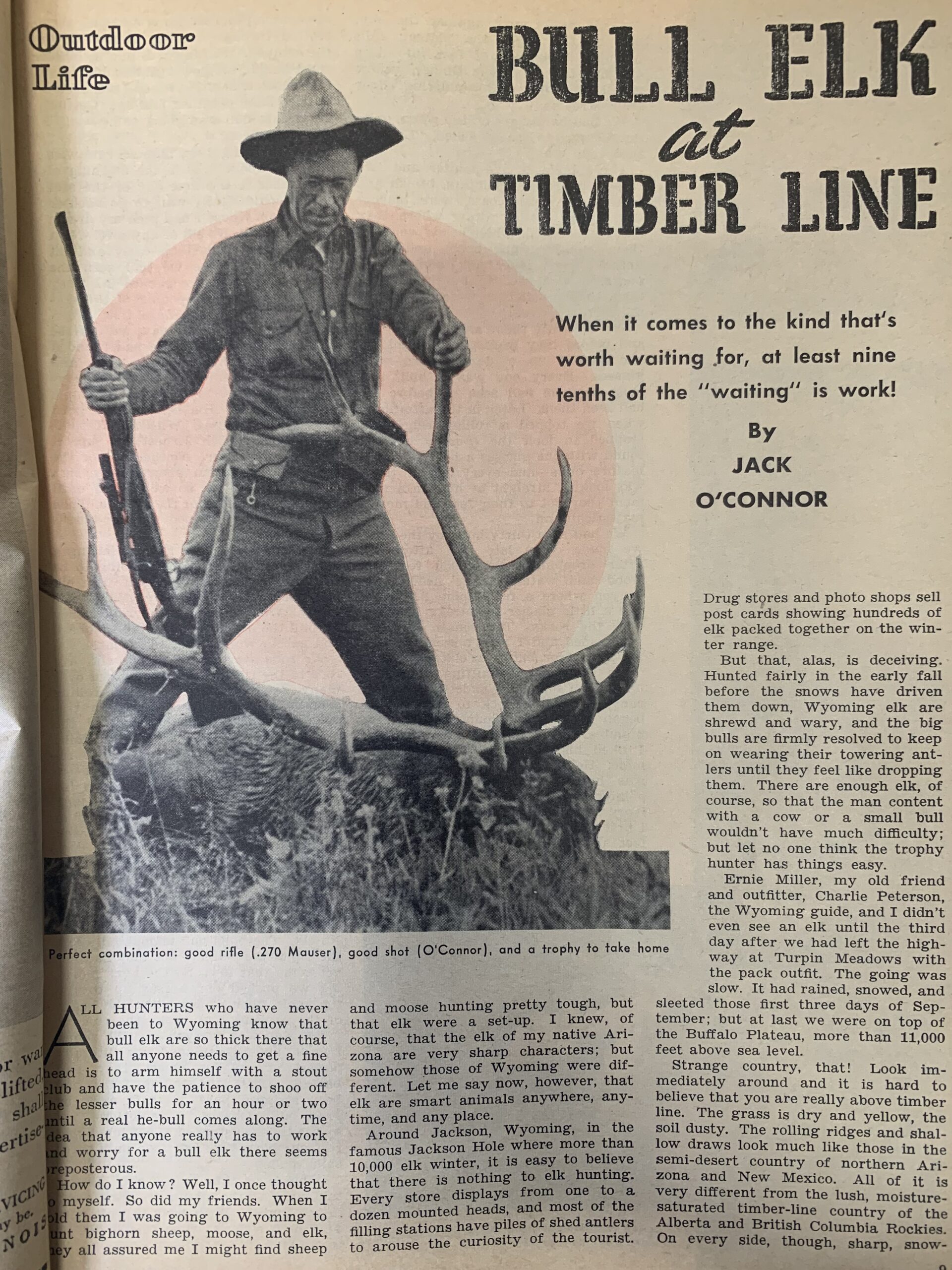

The O’Connor Touch

There is no person or entity more commonly associated with the .270 Winchester than long-time OL shooting editor Jack O’Connor. Hell, even Winchester itself is an ancillary player in the story of the .270 compared to Jack. Any conversation about the .270 without O’Connor — or about O’Connor without mentioning the .270 — would seem amiss.

Despite the fact that the legendary gun writer shot and wrote about every new cartridge and hunting rifle that hit the market for over 30 years, he gravitated to the .270 Winchester often, and is credited widely for its long-lived success.

As he mentioned in some of his writings on .25-caliber cartridges like the .257 Roberts, O’Connor fancied the .270 Winchester for its forgiving trajectory and lower recoil than what the .30/06 and heavier cartridges produced. He used his .270s across the west and the world, hunting everything from groundhogs to elk to African game to mountain sheep with them. His stories, as much as his successful use of the cartridge, gave his readers an emotional connection to the .270 Winchester to match its merit-based appeal.

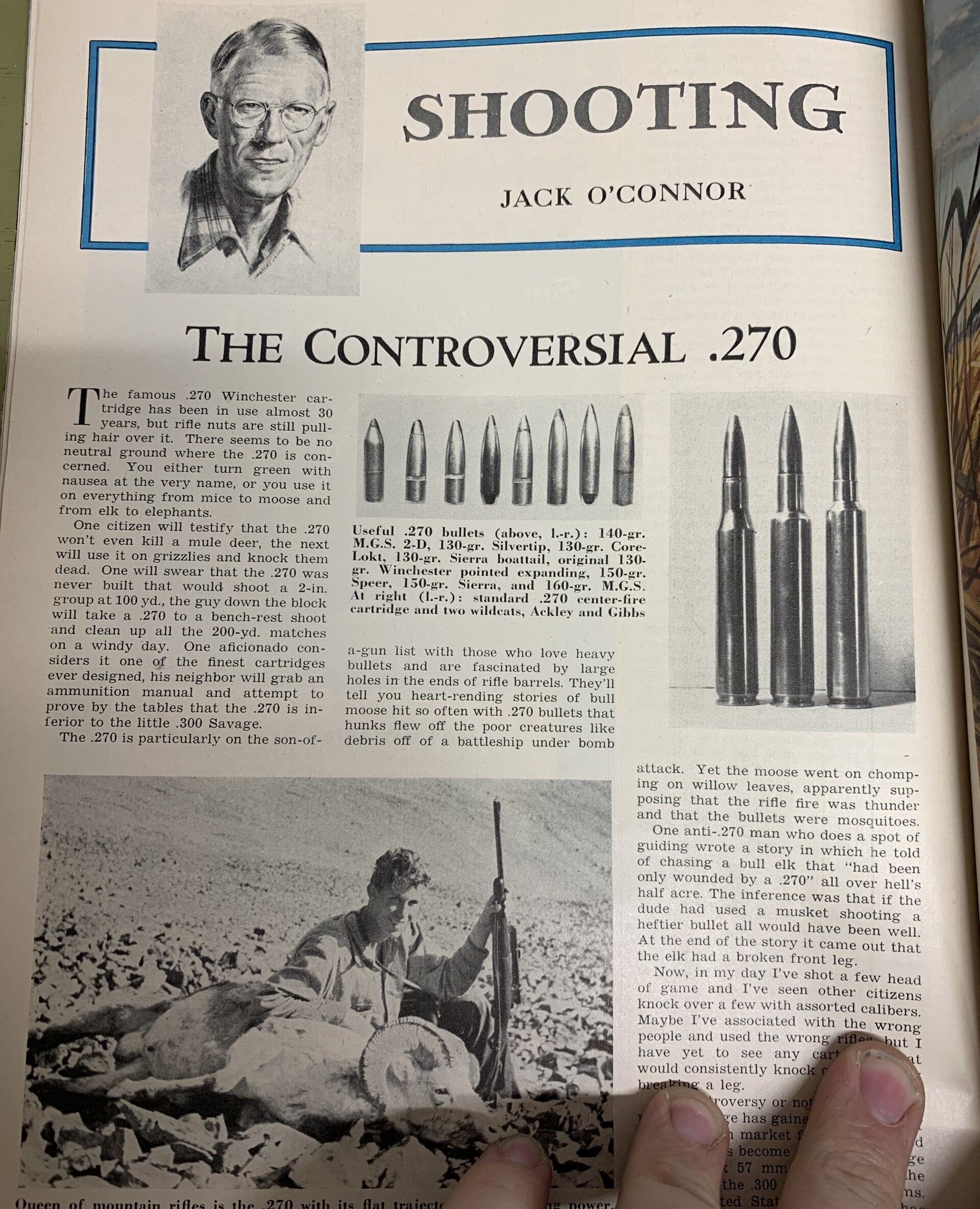

The Beloved .270 Winchester Had Its Haters Too

Because the .270 has been a staple for longer than virtually all of us have been alive, it’s easy to assume that it was always accepted. Times change but people don’t, and the .270 Winchester is an interesting example of that. Today, many people like to besmirch the 6.5 Creedmoor, but even 30 years after it was introduced, the .270 Winchester was still accused of being under-powered.

In the November, 1954 issue of Outdoor Life, O’Connor penned a column titled The Controversial .270. In it, he describes detractors’ gripes against the .270, then makes a strong case for the cartridge based on its attributes.Included among his praise:

“Because of this flat trajectory, high velocity, good accuracy, and mild recoil, the .270 is the easiest standard cartridge to make well-placed hits on game with, at long and uncertain ranges, that I have ever used.”

He goes on to describe how the .270 Winchester is, on the hitting end, a bit of a magnum in itself, with the ability to hang with several magnum cartridges of the day, and concludes:

“The .270 is no rhino cartridge, probably not a good choice to stop charging African lions or Alaska brown bears. But for a flat-shooting, light-kicking, hard-wounding cartridge for any soft-skinned game in the open, from an antelope 400 yards away across the plains of Wyoming to a marmot-digging grizzly in a Yukon basin above timberline, the standard run-of-the-mill .270 is hard to beat. When anyone assures me that the .270 isn’t even a good mule-deer rifle and that .270 bullets bounce off of elk. I cannot help but wonder how much game he has shot with .270 rifles, what kind, and where.”

Read Next: Best Elk Calibers

Is the .270 Winchester Still Relevant in the 2020s?

I believe that much of what hunters and shooters like to argue about when it comes to rifles and cartridges amounts to misunderstanding rather than well-reasoned differences. If we are going to ask whether a cartridge is relevant, or if one is better than another we need to first define the objective, and the criteria by which we’re making our decision. By what metrics are we ascertaining something better or worse? Considering the relevance of a cartridge like the .270 is similar.

Is the .270 Winchester still an effective big game cartridge? Absolutely. In fact, with modern components, it’s more effective than it was in O’Connor’s time. On a performance metric basis (i.e. velocity, energy, and trajectory) the .270 Winchester can still hang with typical factory loadings of many popular magnums, and Browning is now barreling some X-Bolt rifles with 1-in-7.5-inch-twist barrels to handle the longer 165- and 175-grain bullets. It’s still an undeniably wonderful big-game cartridge.

Here’s an example of how the .270 Winchester stacks up against some other common cartridges using the same bullet design in commonly-used bullet weights:

| Cartridge/Load | Muzzle Velocity (fps) | Muzzle Energy (ft-lb) | Trajectory at 500 yards with 200-yard zero (drop in inches) |

| .270 Winchester Hornady Superformance 130-grain SST | 3200 | 2955 | –33.7 |

| 7mm Rem. Mag. Hornady Superformance 139-grain SST | 3240 | 3239 | -32.1 |

| .30/06 Springfield Hornady Superformance 150-grain SST | 3080 | 3159 | -38.4 |

| .300 Win Mag Hornady Superformance 180-grain SST | 3130 | 3917 | -34.8 |

.270 Winchester Accuracy

In the modern era, a downside of the .270 Winchester is that it’s not the most inherently accurate cartridge. There are certainly accurate .270 Winchester rifles out there, but a rifle chambered in .270 is not likely to be as accurate as the same model of rifle chambered in 6.5 PRC or 6.5 Creedmoor. Here’s a look at a couple of .270 Winchester rifles I’ve tested in recent years.

Weatherby Mark V Hunter in .270 Winchester

| Ammo | AVG 5-Shot Group Size @100 yards |

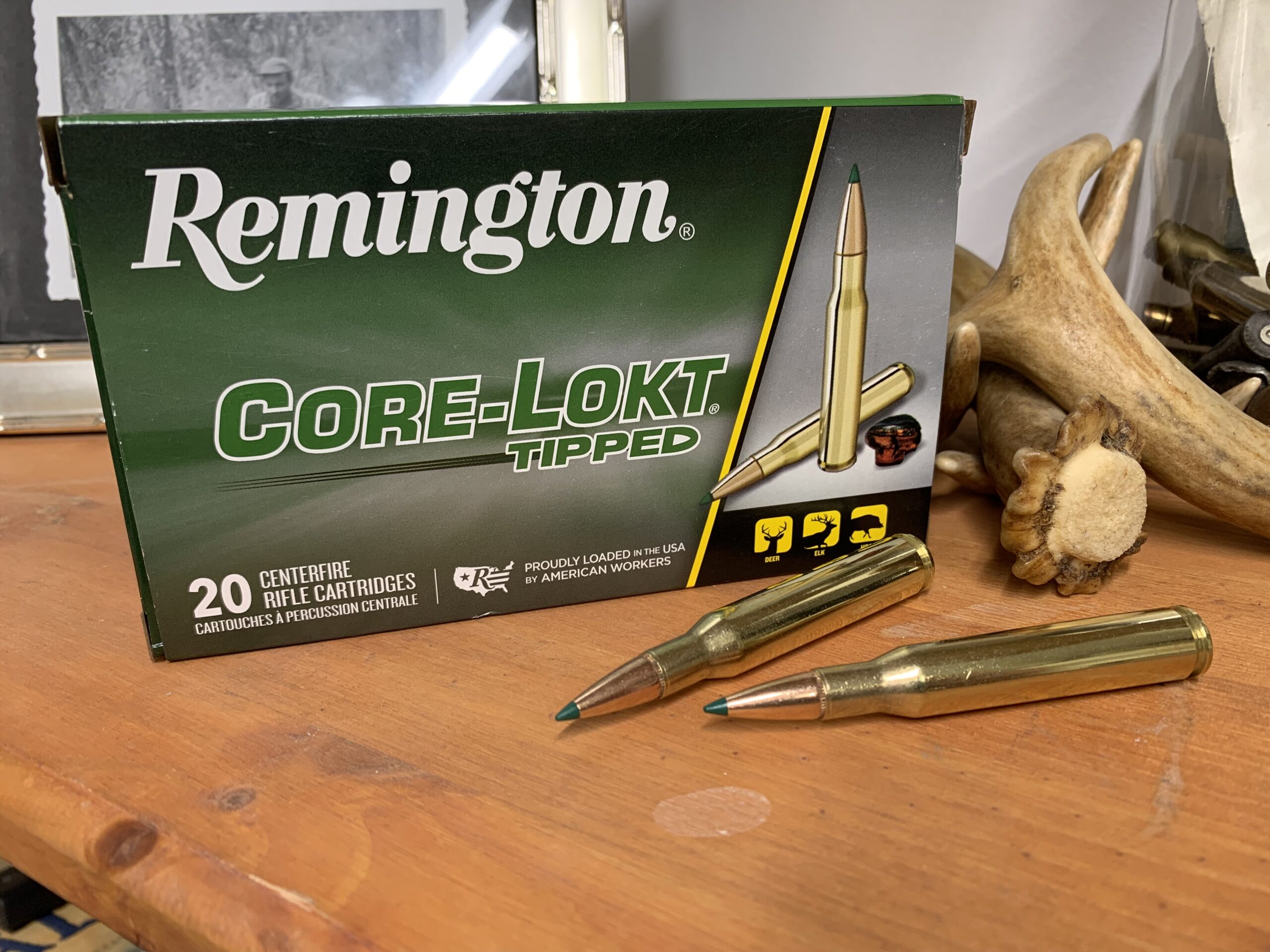

| Remington 130-grain Core-Lokt Tipped | 1.37 inches (10 groups) |

| Federal 130-grain Nosler Ballistic Tip | 1.84 inches (7 groups) |

| Hornady 145-grain Precision Hunter | 1.46 inches (7 groups) |

Winchester Model 70 Featherweight (Push-Feed)

| Ammo | AVG 5-Shot Group Size @100 yards |

| Remington 130-grain Swift Scirocco | 2.6 inches (6 groups) |

What Might Make the .270 Winchester Obsolete?

The matter of the .270’s relevance depends on what we consider relevant. If we’re talking about the cartridge’s capabilities to kill game effectively at any range the average hunter is likely to shoot from, it’s perfectly relevant. The .270 shall never become obsolete then? Not so fast.

As time rolls on, hunters that are buying or building new big-game rifles now aren’t likely to keep flocking to the old classic. That’s not because it doesn’t work, but because there are more-refined options available. For decades after the .270 came to market, it was the flattest-shooting standard big-game cartridge you could get. These days, hot, dirty speed isn’t as important as it once was—because of the range finder. Rather than depending on a light bullet and flat trajectory for unknown distances, we can focus on bullets that hold onto their velocity and buck the wind better. Ultimately those bullets are more forgiving, shoot flatter, and hang onto more energy, at longer distances.

Cartridge Design Has Changed the Game

As current shooting editor John B. Snow is fond of pointing out, nobody today would ever design the .270 Winchester as it is. The principles of modern cartridge design, that most new introductions are following these days, give us cartridges that might not blow the socks off the oldies in terms of raw velocity, but they propel bullets more efficiently, are designed for longer, low-drag bullets, and conform to chamber designs that produce better inherent accuracy. Cartridges like the 6.5 PRC, 7mm PRC, and 6.8 Western embrace the characteristics that are good and impressive about the .270 Winchester, mild recoil and good trajectories, they just execute it better and more efficiently.

For example, the 6.5 PRC can propel a 143-grain, ultra-slippery ELD-X bullet faster than the .270 Winchester can shoot a similar 140- or 145-grain pill, and along a more forgiving flight path. The short, steep-shouldered cartridges typically produce great accuracy in factory rifles with factory ammo too. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for the average .270. Though it was accurate for its day, and some .270 rifles are quite accurate, the average off-the-shelf rifle chambered in .270 Winchester won’t be as accurate as the average 6.5 PRC or 6.5 Creedmoor. A good illustration of this is the Weatherby Mark V Hunter .270 I tested last year. It’s a premium-quality rifle, and out of 34 recorded 5-shot groups, the top 10 averaged 1.2 inches. That’s good, but we regularly test rifles in 6.5 Creedmoor and 6.5 PRC that average under an inch. Standards have changed.

Read Next: Best Hunting Rifles

Pros of Choosing the .270 Winchester

- Mild recoil

- Great velocity and trajectory

- Common components

- Ammo is historically widely available

Cons of Choosing the .270 Winchester

- Mediocre average accuracy

- Limited bullet weights — most .270’s only handle up to 150-grain bullets

- Not “best-in-class” in any category anymore

FAQ

Yes, Winchester’s most common .270 rifle today is probably the XPR.

With the right ammunition and practice, the .270 is effective to 500 yards or a touch beyond.

Ammo for .270 Winchester varies from $1.50 to $4.00 per round, but most quality hunting ammo is between $2.00 and $3.00 per round.

The .270 Winchester uses a .277-inch-diameter bullet, most commonly 130 or 150 grains.

That depends on the shooter and application. The .270 Winchester is certainly more powerful than the .243 Winchester.

The cartridge’s power really depends on how you want to define it and which load you are using. Generally, a .270 is slightly less powerful than a .30/06, but more powerful than a .308.

The .270 Winchester is ideal for hunting deer-sized game, but also works well on elk, moose, and bears.

The Future of the .270 Winchester

Though I have no doubt that the .270 Winchester will rightly march on, I’m not the guy that’s going to charge through hell and cannon shot, purely for the folly of keeping the colors aloft. The .270 has seen its glory days, and it’s the cartridge’s — and Jack O’Connor’s — legacy that will remain most impressive. The .270 Winchester was a remarkable cartridge for its time, and it can kill critters just as dead a hundred years later. However effective, hunters that go out of their way to choose the .270 today are probably doing it for nostalgia’s sake as much as performance. There’s not a damn thing wrong with that.

I don’t see a bountiful future for the .270 Winchester’s next hundred years, but it’s a cartridge that’s been underestimated before. In this case, it would warm my heart to be wrong.