We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Editor’s Note: One current fad among outdoorsmen is to bash 6.5mm cartridges, with the 6.5 Creedmoor being the particular target of ire for this vocal minority of malcontents. But the emergence of that cartridge, and the also impressive 6.5×47 Lapua and 6.5 PRC were no accident. There had been a growing trend for decades to come up with the best 6.5mm cartridge that leveraged the recent advancements in ballistic technology. With better powders, bullets and a refined sense of cartridge design, accuracy-obsessed riflemen, like my predecessor as Outdoor Life’s shooting editor, Jim Carmichel, were pushing the boundaries. This story details his development of the 6.5 Leopard and some earlier efforts with 6.5mm cartridge wildcats. Outdoor Life first published this story in 2005, two years before the 6.5 Creedmoor was introduced. One interesting thing about the Leopard is that it anticipated the arrival of both the 6.5 PRC, which is a consummate long-range cartridge for shooting steel and is one of the finest open-country hunting rounds available today, and the 6.5 SAUM, which is another short-fat 6.5 magnum that has its virtues but is already fading in the 6.5 PRC’s shadow. —John B. Snow, shooting editor

Nothing makes the heart of a confirmed wildcatter beat faster than the first time he sights-in a new cartridge. The rush of adrenaline is brought on not by the cartridge itself but by the possible ways in which the case might be squeezed, inflated, cut off, necked up or down or otherwise mutilated.

Come to think of it, reaction may be similar to the palpitations of a frat boy at spring break upon viewing a sunny beach sparkling with bikini-clad nymphs. This pretty well sums up my reaction at the first glimpse of Winchester’s .300 Short Magnum. But rather than speculating on various ways to modify the case, I knew instantly what I intended to do with it. It was almost as if the pudgy little case was speaking to me, saying, “Yes, let’s do it. I’m just a plain-Jane .30 now, but in my heart I really want to be a sexy six and a half millimeters!”

The scene was a hunting club in the wilds of Arkansas where some big shots from Winchester ammo and Browning Arms had gathered a bunch of gun writers to preview the Short Magnum cartridge and attendant rifles with which they were to stun the shooting world a few months later. After a few rounds of shooting I collected a small bagful of fired WSM cases, which would become the nucleus of my first experiments with the WSM necked down to 6.5mm.

I’m in the habit of giving my wildcats cat-themed names, beginning with the racy .22 CHeetah, followed by the 6mm CHeetah, the .260 Bobcat, the .264 Panther and the .243 Catbird that Kenny Jarrett and I worked on together. But what to call this latest?

There was a name I’d been saving for a new cartridge that possessed a special feline blend of speed and accuracy, and as load development and range testing progressed it became obvious to me that this was the round that deserved to be named after the quickest and deadliest cat of all-the leopard!

But why 6.5mm instead of, say, .25 caliber or 7mm? Simply put, the 6.5 (.264 inch) stands alone and apart from other calibers in its class. Historically, 6.5 cartridges have been loaded with bullets that have a particularly high weight-to-diameter ratio. Military cartridges, such as the 6.5×52 Italian Carcano, 6.5×50 Japanese, 6.5×54 Mannlicher and 6.5×55 Swede, are typically loaded with bullets in the 160-grain weight range.

The high sectional density of these 6.5 bullets tends to give them great retained velocity and energy, better wind resistance and deeper penetration. This is why the little 6.5×54 M.S., loaded with 160-grain full-jacket bullets, was a favorite of many professional elephant hunters. From an accuracy standpoint, various 6.5 cartridges ruled 300-meter Olympic rifle competition for many years, and the 6.5 is increasingly popular in today’s medium- to long-range competition. As a result of these successes in the field and on target ranges, there is a superb assortment of 6.5 bullets available to the handloader and experimenter, which, of course, makes the 6.5 especially attractive to wildcatters such as myself.

The 6.5 Cartridge Story

Cartridges of 6.5mm caliber have been around for over a hundred years, with the old-time favorites being joined more recently by the increasingly popular .260 Remington. And there’s also nothing all that new about attempts at “magnumized” 6.5’s made by the ammo industry and wildcatters. If we dig back all the way to 1913 we find that the Western Cartridge Co. loaded a 6.5 round called the .256 Newton, for which a muzzle velocity of 2,760 fps (feet per second) with a 129-grain bullet was claimed. Newton was a famous wildcatter and experimenter of his era, and his .256 was simply the .30/06 case reformed and necked to .26 caliber. Since then there has been an endless stream of 6.5 wildcats based on the ’06 case and most of them are pretty good.

Back before World War II, the German ammo firm of RWS listed a hot 6.5 round called the 6.5×68, for which it claimea velocity of 3,450 fps with a 123-grain bullet. A handful of rifles in this caliber were imported into the U.S., but generally speaking the 6.5 caliber (and most other European “metric” calibers) didn’t excite American sportsmen-an attitude that continued to prevail when Winchester launched its .264 Win. Mag. back in the 1950s.

By all reckoning, the .264 Winchester Magnum should have been a smash hit. It had a belted case, which was all the rage then, and claimed a sizzling 3,700 fps velocity with 100-grain bullets and 3,200 fps with 140-grainers. Those velocities were presumably from the 26-inch barrels of the M-70 rifle Winchester called the “Westerner.” But the 6.5 curse held firm and Winchester’s great expectations withered.

An even sadder 6.5mm story is the misbegotten 6.5 Rem. Mag. introduced back in 1966. I say misbegotten because of the almost comic mismatch of the cartridge and stubby-barreled Model 600 Remington rifle with which it was paired. Talk about the odd couple…

So, given the chronic failure of past attempts at a “magnum” 6.5-caliber, why should I be taken with the notion to give it another try? Actually, there are several good reasons, beginning with the fact that the timing, conditions and demand are upon us. Anyhow, I’ve been smitten with possibilities of 6.5 bullets ever since I began experimenting with them several years ago. [BRACKET “See “The Ultimate Caliber,” September 1995, and “The Best Deer Cartridge Yet?” January 1997.”]

Meanwhile, another 6.5 wildcat, based on the .284 Winchester case (which recently became known as the 6.5-284 Norma when the Swedish firm began making dedicated brass) has been having considerable success in long-range target competition. With bullets in the 140-grain range, the MV (muzzle velocity) of the 6.5-284 is around 2,900 fps. Obviously, this is a velocity improvement over the highly accurate but slower .260 Remington, another target and hunting favorite that maxes out at about 100 fps slower.

A New Idea

But why not make a bigger jump, say to about 3,200 fps with a 140-grain bullet? The flatter trajectory and reduced wind drift of the higher-velocity load would be a definite advantage for longer-range hunting and target shooting.

During the golden age of wildcatting, experimenters had only to look to .30/06 and belted magnum cases for inspiration. Hence, the 6.5/06 in its many incarnations and serious barrel scorchers such as the 6.5-300 WWH, which is the .300 Weatherby necked down to .26 caliber. But those days are pretty well past, with current thinking focused on accuracy as well as velocity, especially the “fat-and-short” case concept. This is why the rotund and conspicuously beltless .404 Jeffery case has been the mother of several new caliber configurations of late. (Usually by simply shortening and necking down to a variety of calibers.) In other words, the .404’s greater body girth yields greater propellant capacity than a standard H&H-type; belted case of the same length, or, considered another way, equal capacity in a shorter form.

This is a concept that enthralls apostles of accuracy because, according to current ballistic thinking, a volume of propellant ignites and burns more uniformly in a short, fat case. There is ample evidence to support this, most notably in the squatty “PPC”-type cartridges that have dominated benchrest competitions for the past several years. Necking the .300 WSM case to 6.5 is perfectly in tune with this trend in that it would duplicate the external ballistics of, say, the .264 Win. Mag., but with an added accuracy bonus. Plus, the shorter round would also fit shorter and stiffer rifle actions, yielding a double accuracy bonus.

Birth of the Leopard

Obviously, necking the spanking-new WSM case down to 6.5 caliber was a wildcat just begging to be born. But building a wildcat from scratch is considerably more complicated than it sounds, especially when there are no existing chambering reamers or loading dies. So my first move was to send samples of the WSM case to JGS Precision Tool Company in Coos Bay, Ore., which has made chambering reamers for my other wildcats. The folks there made drawings of the proposed cartridge and ground sets of reamers for making loading dies and for chambering barrels. According to my concept, the dimensions of the WSM were to remain the same with the exception of the smaller neck. Loading dies for the proposed round, which I then called simply the 6.5-300 WSM, were made by Redding, and a well-lubed .300 WSM case could be necked down in a single operation. Since then, .270 WSM brass has become available and is even easier to neck down.

The next step in the process was chambering and fitting a test barrel with a heavy, 26-inch, air-gauged, XX-grade Douglas barrel. The barrel has a 1-in-9-inch twist and was fitted to a Remington M-700 short action and the bolt was modified for the larger WSM rim.

During wildcatting’s heyday, very few handloaders had access to-or even knowledge of-the expensive and complicated pressure-measuring equipment used in the ammo industry’s labs, so pressure was “measured” by flattened or blown primers, bolt lift and other primitive means.

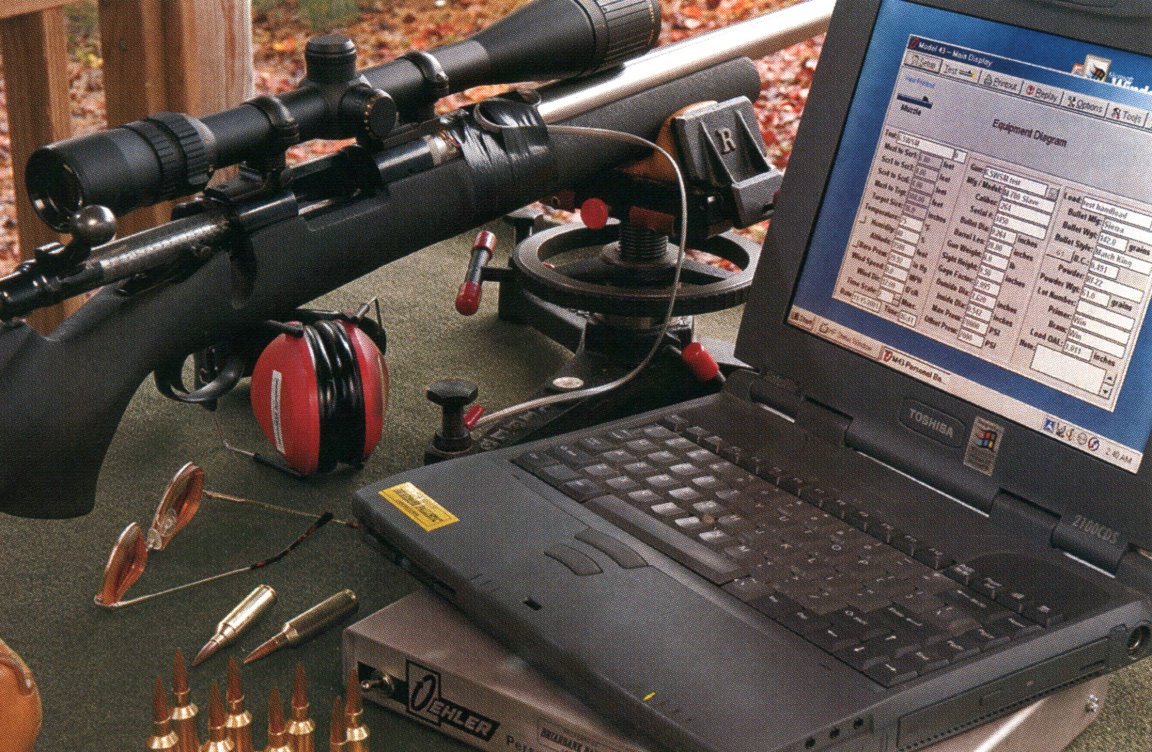

Nowadays, however, thanks to the Oehler M-43 PBL (Personal Ballistic Lab), serious experimenters can measure pressures and thus avoid the previous pitfalls of wildcatting. The PBL is portable enough to be carried to the shooting bench and flexible enough to measure and record velocity and pressure while at the same time allowing test firing for accuracy. This is why an M-43 was used throughout development of the 6.5 Leopard.

So just how quick is this Leopard? And how accurate is it? Despite predictions to the contrary, the accuracy of Sierra’s 142-grain Match King bullet actually tended to improve as velocities increased. At 100 yards, five-shot groups of a half inch or so were routinely at the 3,200 fps level, and lighter bullets also did their best at top velocities (see chart). But remember, these small groups were fired with an accurate, heavy-barreled test rifle under ideal conditions.

Will the 6.5 Leopard be adapted by mainline ammo and rifle makers or will it forever remain a wildcat? My best guess is that something identical or similar is already in the works. Remington’s 7mm Short Action Ultra Mag. cartridges, for example, would be an excellent vehicle for a 6.5. And come to think of it, a company with a “magnum” tradition, such as Weatherby, would do well with this or a similar cartridge in a short-action Weatherby rifle. Good wildcats tend to turn up in factory dress, so we’ll know in a year or so.