The author came to Canada from England in 1923 as a 23-year-old greenhorn. During the next five years he traveled in the wilds of Canada and Alaska and discovered gold near Frances Lake in the remote southeastern Yukon. In the June OUTDOOR LIFE Money told about a 650-mile dogsled trip back to his cabin at Frances Lake in 1928 with his bride and infant son. Last month he described their first spring and summer at the cabin. Here he tells how they harvested the game and fish they would need for the long winter ahead.

THE GLORIOUS SUMMER passed all too quickly. Frosts began in August, warning me that months of blizzards would be starting soon. I had several Liard Indians working with me at my gold diggings, but by the middle of September I had to close the operation for the season. I discovered that fine gold was being carried out of the sluice-box tailings by skim ice.

Caesar, one of the Indians, helped me clean up the last of the gold and stack away the equipment. I paid the men with gold coins and a lot of trade goods.

Later, at the cabin, my wife Joyce helped me weigh the summer’s production from the mine. Our profit was astonishing, and we delighted in planning ahead to the next year’s mining. At the going rate of $20 an ounce for gold dust and nuggets, our summer’s take would net us about $8,000.

After spending over half a year in the wilderness, we were getting low on supplies. But I’d anticipated that problem. Months earlier I’d left an order for more trade goods and supplies to be shipped from the Taylor-Drury Company in Whitehorse to their remote Pelly Banks Post on the Pelly River. That post was across a mountain range and about 75 miles from our cabin. When snow travel became good, I would run my six-dog team to the post and freight the supplies home with our toboggan. Meanwhile, I had to harvest our winter’s supply of game and fish.

In September, whitefish swim clockwise around Frances Lake in shallow water near shore. I had a 50-foot-long gillnet, so I had little trouble catching as many as 50 whitefish and lake trout a day. I set the net with a 22-foot boat I’d built from whipsawed lumber.

Each evening, we would pull the net, untangle the fish, and whack them over the head. I’d gut them in a big zinc washtub, then throw them into another tub where Joyce washed them clean. Together we hung our fish over racks in the smokehouse, where willow-brush fires dried and smoked them in about three days. Then we put them in gunnysacks and stored the loads on top of a highpoled cache.

“We’ve got about two-thousand fish dried now,” Joyce said one night. “Isn’t that enough for winter dog food and our own emergency rations?”

I decided it was, so we pulled in the net and began taking care of our garden produce.

The garden in front of the cabin was fully grown. Potatoes. carrots, turnips, onions, and all the other vegetables had grown well. I dug and cleaned the crops. We put most of them in a storage cellar that we had dug under the middle of the cabin floor. We left our cabbages in the garden to freeze.

There was one last job to do before we planned our fall hunt. After snow came we would build a big new cabin measuring 24 by 22 feet. I had to dig trenches for base logs before the ground froze.

When I finished that job, I told Joyce about my hunting plans.

“The trip will be fun,” I began. “We’ll take the boat and sail thirty miles down this arm of the lake to where it joins the east arm. Then we’ll travel up that arm to its far end. A partner and I discovered a silver-lead claim there three years ago. You’ll enjoy looking at the veins of ore. Above the claim is high, beautiful country that’s tops for moose and mountain goats. We shouldn’t have any trouble picking up plenty of ducks and a few geese along the way.”

Joyce was especially pleased with the plans because they offered her and our baby son Sydney a change in routine. Syd by then was one year old. He was able to walk a bit and interest himself in new surroundings. Often he rode around on the back of Rogue, our lead sled dog. Both the boy and the 115-pound Siberian husky enjoyed their games. When Syd would fall off Rogue’s back the dog would stand still and wait for Joyce to place the boy back in position. We were sure that Syd would enjoy a new world of play during the hunt.

We loaded the boat with our camp outfit and plenty of fresh food; then we set sail down the lake the first morning we had a wind from astern. My makeshift canvas sail caught the wind efficiently, so all I had to do was steer. Nothing could have been more restful and relaxing than sailing smoothly down the long waterway.

High mountains, already capped with first snow, hemmed in the jewellike waters. Trees, especially birches and willows, displayed a glory of fall colors. We steered past the big Il-es-tooa River delta and on past the islands toward the south end of the lake. By eating lunch afloat we reached the junction above the foot of the lake where the east arm enters the west arm. A scenic narrows made an ideal campsite.

We had let the dogs loose back at the cabin. taking only Rogue in the boat with us. The others ran along the beach. As soon as I had the family safely ashore I took the boat and fetched the other dogs from across the narrows. Then I tied them to trees and gave each one a dried whitefish. We made our own supper over an open fire.

This was like old times, camping out again and cooking outdoors instead of on the stove. Joyce and I sat up late beside the fire, watching the stars come out one by one and listening to the gentle lapping of waves on the beach.

At my first sweep with the glasses I saw no big game, just flocks of ducks on almost every little lake. Then, as I was about to get up and try for goats, I saw something move.

The north wind kept blowing the next day. We were heading into it now, and I had to row with the heavy, homemade oars. The lower end of the east arm is a series of small lakes and bays connected by narrow channels, so the dogs had to run around irregular beaches to keep up with us. About 2 p.m. the wind strengthened and waves started piling up. It got too risky and difficult to row, so we pulled into a small bay and made camp early.

After getting settled I searched the mountains across the lake with field glasses. Almost immediately I spotted a herd of goats. They were climbing around steep walls of the peaks above the silver claim. We watched them for an hour as they grazed along an old talus slope partly overgrown with grasses and lichens. I would be able to hunt them from where I planned to make our camp.

We found some currant bushes, and Joyce went picking while I took my Stevens single-shot 12 gauge shotgun and walked to the next bay, where I could hear ducks quacking. I kept to the light brush away from shore and came over a small rise that sloped down to the bay. I counted 11 mallards swimming close together within easy range.

Holding an extra shell in my hand, I sighted carefully at a knot of the birds and fired. Without looking to check results, I reloaded as fast as I could. The surviving ducks were just getting into the air when I let go a second shot, which dumped a single bird. I retrieved three mallards that had been downed with the first blast and then waited while the wind drove the fourth duck to shore.

The next morning, we came to the last narrow neck in the huge lake. From there on the water spread out to about two-miles wide all the way to the head of the east arm where the silver claim was. We made camp at the mouth of a creek, in the same spot where I’d camped with my partner at the time we had located the claim.

Before going to bed I took 100 yards of 25-pound-test line and knotted it to a No. 2 hook. I weighted the line with a four-ounce lead sinker and baited the hook with a small chunk of moose meat. Then I swung the works in circles and pitched it out from shore.

As I pulled the line in hand-over-hand, a fish struck. It fought hard but never broke water until I, worked it close to the beach. It was a five-pound pike. I rebaited with the pike’s liver and tried again. Seven or eight casts produced three more pike. Any that we couldn’t eat we would feed to the dogs. Surely a man need never go hungry in this land, especially when living on a lakeshore.

I had planned to make our last camp at timberline two miles up the mountain, but Joyce decided it would be better for the family to stay in the lakeside camp. They could have fun on the beach, and blackflies were fewer there than up on the mountain.

The next morning I cut a stack of kitchen wood and banked up dirt around the bottom of our 8 x 12-foot silk tent. Then I selected four close-together trees and cut them off 10 feet above the ground after making a ladder from stout poles. On top of the stumps I made a crude cache for the meat we hoped to get. It was just a 6 x 8-foot platform of poles, but it took me all day to build it.

I was up before dawn. The sun was just topping the mountains to the southeast as I walked alone over the brow of the first slope and came out onto a mile-wide swampy flat. I stopped beside a creek to rest and scan the flats for moose with my field glasses. I didn’t spot game, so I sloshed my way through the swamp and gained the higher ground on the other side.

Climbing ever higher, I passed the last growth of stunted spruce and balsam and could look back onto the miles of swampy flats, lakes, and patches of heavy timber. I sat down and glassed the area from one end to the other. Deep ruts of game trails led in and out of heavy willow growths and into small clearings between stands of thick spruce. At my first sweep with the glasses I saw no big game, just flocks of ducks on almost every little lake. Then, as I was about to get up and try for goats, I saw something move.

I zeroed in with the glasses and spotted a bull moose browsing in a stand of willows a mile away. I angled back down the mountain and into the timber, heading almost into my own shadow so that I could keep a steady bearing and come out at a lakeshore close to the bull.

My soft, wet moccasins pressed lightly on the ground as I approached my destination. I slid my pack and field glasses off and left them near the lake. Listening, straining to catch a sound from the feeding bull, I edged closer to the open glade where I knew he must be. Suddenly I stopped dead in my stride.

A huge cow moose was standing motionless beside a spruce 50 yards ahead, facing the open glade. She did not see me, nor, apparently, had she heard me. The wind brought her scent to me as I stood wondering what to do. If I killed the cow, the shot would surely send the bull charging away. But if I tried to bypass her, she might stampede and scare the bull off and I would lose both.

I lined the cow up in my open sights, aiming to strike her heart, and pressed the trigger of my bolt-action Winchester .30/06. She fell as if clubbed. I ran immediately to the cleating, hoping for a glimpse of the bull. I could hear his antlers smashing through branches as he ran up the hill through heavy timber.

I retraced my steps to the big cow and gutted her out. Though the hour was still early afternoon, it was too late to climb the peaks and hunt goats. I skinned out the moose and quartered it, covering the meat with the hide to keep flies off. The next day I would begin packing it to camp with the dogs.

The next morning the family and I started up the mountain, with one dog carrying our tea kettle and lunch, another packing cartridges, shotgun shells, and other gear. Joyce carried the shotgun while I shouldered the .30/06 and had Syd in a packsack on my back. I took the rifle along in case a grizzly had got wind of the meat and decided it was his. I chained the dogs in pairs so that they could not run off if they scented game; at least they wouldn’t get far before they tangled around a tree.

The slope was a tough climb for Joyce. We were in no hurry, so we rested often beside the creek. The air temperature had been dropping fast the last few days. It was about 10° when we started out, but the sun soon ·warmed us even though the wind gusted down from the snow-capped mountains.

The clashing of antlers was unmistakable. I peered through the trees and saw a spectacular sight. The young bull I’d been hunting was larger than I had suspected. He was standing 30 yards away and facing a huge older bull.

When we came to the lake where the ducks were, we tied the dogs and hung our packs in trees. Joyce and Syd watched while I got soaking wet by stalking low in the tall grass and working toward the water’s edge. With my single-shot gun I had to be very sure of lining up at least a couple of ducks. I was in a foot of water and getting cold when I straightened up from my crouch and let go at a dozen mallards about 20 yards away. The survivors jumped immediately into the air, but I had time to eject the spent shell, reload, and fire again. The two blasts killed five prime birds.

We made lunch beside a lake close to the moose kill, a mile from where I shot the ducks. I cut the moose into pieces small enough for dog·packs. The six dogs would have to make three trips to carry it all down the mountain. I left the family with the dogs at our lunch camp and hunted another lake, getting three more ducks before we started back.

The dogs each carried 40-pound packs, and the load kept them right on trail behind us. We got back to our lakeside camp tired but very happy with our success. The next day I took the dogs alone and made the two trips to pack out the rest of the meat.

The nights were cold now, but it would take about three weeks to freeze the meat solid. I cut off the heavy fat and stored it apart. The moose’s rump had four to five inches of solid hard fat that would make wonderful shortening and cooking oil when rendered down. The meat would keep until the next May if stored in shade. After it was frozen and hanging I would cover it with a film of fat to prevent it from drying in temperatures of 30 to 40 below.

During breakfast in the tent the next morning we heard a splashing in the lake. Then the dogs went wild with yelping and barking. I grabbed my .30/06 and jumped outside. A young bull moose was breaking out of the water and climbing ashore 300 yards away. He must have swum clear across the two miles of water before striking the beach near our camp.

The bull turned away as soon as he was ashore, but I dropped him while he was crossing the beach. He was a two-year-old and would be excellent eating. What wonderful luck to have a fat young moose walk almost into camp.

A flurry of snow settled over the tent and brush during the night. The next morning began a good day to hunt, especially for moose, since the snow would show fresh tracks.

The air was clear and cold with a slight west wind as I climbed the mountain to the same lookout I had glassed from the first day. After an hour of fruitless looking through the field glasses, I abandoned the lookout and followed along the side of the mountain just above timberline. Then I worked my way down through heavy timber where light snow still held on the ground. Snow-shoe-rabbit trails crisscrossed through the trees. Squirrels scolded me.

I came out of the timber onto the edge of a Jake where many well-worn moose trails led in and out of the water and back into the timber. I followed one set of fresh tracks that looked to have been made by a bull three or four years old. The tracks were already well-rounded at the point of the hoof, showing that the bull had been pawing the ground. The big hoofprints led into the wind for perhaps a mile, then circled downwind. The bull had obviously headed to a feeding place where he would be able to scent anything following him.

I backtracked a half-mile down the mountain toward the lake and then struck east. I kept the wind behind me for a full mile until I figured that the bull wuull.l be half a mile or more up the mountain and certainly west of me. Then I climbed up through heavy timber and, when I reached the bull’s probable elevation, circled into the wind. I stopped to listen every few steps but heard nothing. The mountain slope leveled out, -and I saw a willow swamp through the trees.

Suddenly I heard a crash and thought I must have spooked the animal. The crashing noise came again, clearer this time, and instantly I knew what it must be.

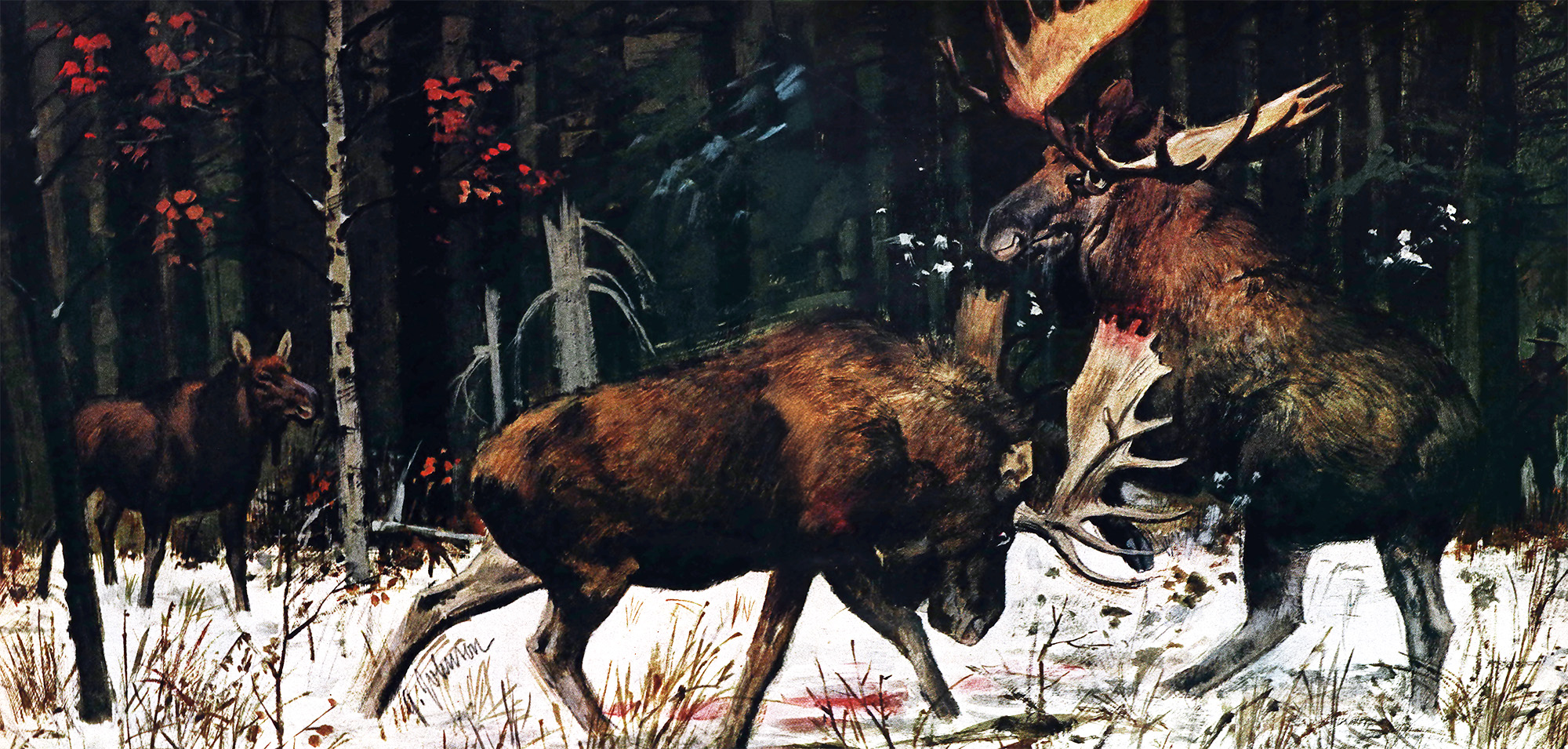

I crept closer, climbing up the steeper slope away from the willow swamp until I came into an area that was half meadow, half heavy timber. The clashing of antlers was unmistakable. I peered through the trees and saw a spectacular sight. The young bull I’d been hunting was larger than I had suspected. He was standing 30 yards away and facing a huge older bull. Both were pawing the ground and snorting. The larger bull was defiant and was swinging his magnificent antlers from side to side. A cow moose stood by, apparently unconcerned.

The old bull was bleeding badly from a cut in his right shoulder. His opponent took a few steps forward, then leaped full tilt into a charge. The big bull reared up, came down with a thud of hoofs, and thundered into action. The combatants met head-on with a resounding crash. their huge bodies rising under the terrific impact, which fairly shook the ground.

The two bulls locked antlers and struggled, half stunned by the collision, each trying to throw the other. Then they pulled back and tried to rip each other with swinging antlers.

The young bull reared up to strike a death blow with his front hoofs, but before he could start the downward strike the cunning old master, moving with surprising agility, stabbed him in the neck with a fast sideswipe of his six-foot- wide rack. Blood gushed from the wound. The young bull stood still as if incredulous that such a thing could happen. Then he turned away and began staggering downhill toward me.

The old bull limped a little as he walked with magnificent pride past his waiting cow. A second cow can1e out of the woods and followed him.

The young bull was in bad shape; blood was coming fast from his neck as he passed within a stone’s throw of me. I spared him further pain by shooting him through the heart.

A storm blew up two days later. We awoke that morning to the pounding of waves on the beach and the screaming of wind in the treetops. As daylight broke through the clouds we found six inches of snow surrounding us. The storm blew itself out by noon, so I took the shotgun and went up to the first lake for ducks. Before I visited the third lake I wished I had brought a couple of dogs to pack for me. My packsack was bulging with mallards and getting heavier every time I blasted at a rising flock.

I gutted the big birds, put them into my packsack, and staggered back to camp under the load.

The next morning I hiked along the beach and then climbed up the creek valley to a bigger lake. It was just getting light enough to see when I noticed some movement along the shoreline. I knew I was looking at ducks or geese. I stalked through the trees till I was close enough to identify the birds as Canada honkers. About 12 or 15 of them were chattering away like a cageful of monkeys. They moved around on a strip of sand, walking back and forth to the water’s edge.

I got within 30 yards of the geese before I had to break cover. With a great flurry of squawking they ran for the water. I blasted them as they ran. By reloading I got off three shots before the honkers got into the air and out of range. I had downed five of them.

What a larderful we had now over 20 ducks, five beautiful geese, and three fat moose. We could shoot spruce and ruffed grouse almost anytime, for they stayed continuously on the delta near the cabin. I gutted the big birds, put them into my packsack, and staggered back to camp under the load. We were delighted to have geese. We could use one for Christmas and one for New Year’s dinner; the others would make real feasts for other special occasions.

Deep snow was now on the ground at higher elevations, so I decided to cancel my goat hunting. It would have meant scrambling around high ridges and slides and risking an injured leg or other troubles.

Read Next: The Top Moose Cartridges and Bullets

The next morning we loaded the meat in the boat, broke camp, and started the 50-mile trip around the lake. All the little bays were covered with thin ice. We were glad to get through the narrows and into the west arm of the lake before making camp.

The next afternoon we arrived home at our snug cabin and began filling the big cache with our supply of meat. It had been a wonderful and successful hunt. We had no worries about eating well for months.

In the next issue of Outdoor Life I’ll tell about our first winter at the lake, when I built a big new cabin, studied wildlife, and made an exciting hunt for caribou.

This story, “A Hunt for the Larder: A Bride Goes North, Part Three,” first appeared in the August 1972 issue of Outdoor Life.