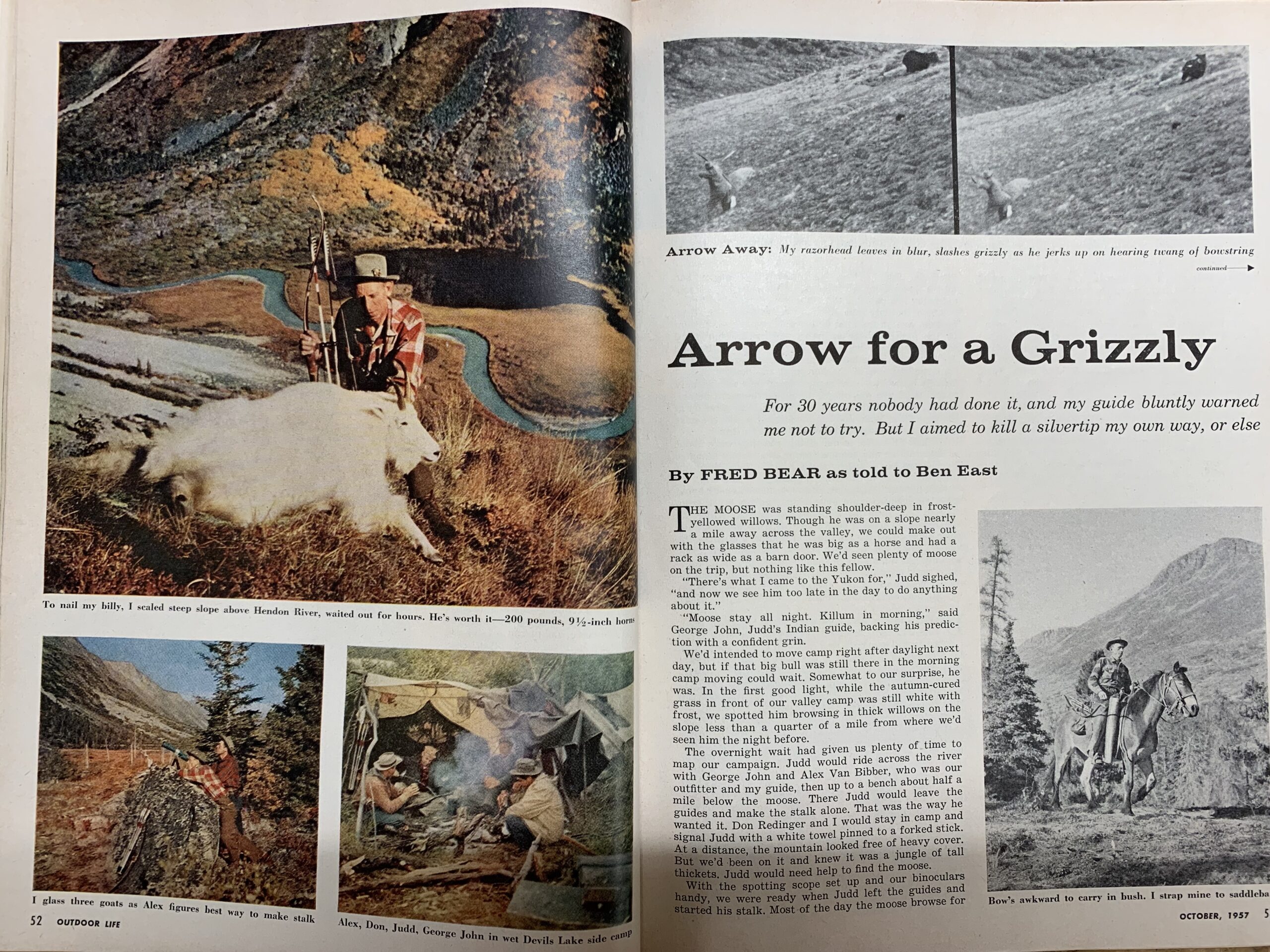

Incredible stories have been told in the pages of Outdoor Life and, every now and then, we dust one off to be republished online. This story comes from one of my favorite vintage issues of OL: October 1957. “Arrow for a Grizzly” is a historic story, and not just because it’s by Fred Bear or because it was about a true safari-style horseback expedition into the Yukon, although those certainly don’t hurt. It’s a look into a key time when Bear was developing the now-legendary Razorhead broadhead. This was the first grizzly Fred Bear killed, and the hunt was also captured on film (which is embedded below).

This story is transcribed as it appeared in the original issue of Outdoor Life. There’s certainly a little embellishment here and there, and it’s interesting to compare the written story to the video. But more than anything, it’s fun to simply read, watch, and enjoy this adventure for what it is. —Tyler Freel

Arrow for a Grizzly

By Fred Bear, as told to Ben East

THE MOOSE was standing shoulder-deep in frost-yellowed willows. Though he was on a slope nearly a mile away across the valley, we could make out with the glasses that he was big as a horse and had a rack as wide as a barn door. We’d seen plenty of moose on the trip, but nothing like this fellow.

“There’s what I came to the Yukon for,” Judd sighed, “and now we see him too late in the day to do anything about it.”

“Moose stay all night. Kill ’em in the morning,” said George John, Judd’s Indian guide, backing his prediction with a confident grin.

We’d intended to move camp right after daylight next day, but if that big bull was still there in the morning camp moving could wait. Somewhat to our surprise, he was. In the first good light, while the autumn-cured grass in front of our valley camp was still white with frost, we spotted him browsing in thick willows on the slope less than a quarter of a mile from where we’d seen him the night before.

The overnight wait had given us plenty of time to map our campaign. Judd would ride across the river with George John and Alex Van Bibber, who was our outfitter and my guide, then up to a bench about half a mile below the moose. There Judd would leave the guides and make the stalk alone. That was the way he wanted it. Don Redinger and I would stay in camp and signal Judd with a white towel pinned to a forked stick. At a distance, the mountain looked free of heavy cover. But we’d been on it and knew it was a jungle of tall thickets. Judd would need help to find the moose.

With the spotting scope set up and our binoculars handy, we were ready when Judd left the guides and started his stalk. Most of the day the moose browse for half an hour at a time, then lay down. Watching our signals, Jud sat tight when the moose was down, then resumed his stalk every time the bull got up to feed.

It was an exciting game of hide-and-seek to watch, and it went on for hours before Judd got where he wanted to be—just 25 yards from the moose. The bull was in the open, and our scope showed us he was staring down at us, possibly puzzled by the white flash of our signal towel. Don and I waited for Judd to shoot. Then suddenly the moose slewed around and vanished in the willows. That was that.

Judd came in alone after dark, disappointed but not dejected. It must have looked easy from where we sat, he agreed, but it wasn’t so simple over there on the mountainside. He’d been close enough a dozen times to nail the bull with a rifle of almost any caliber. But this was a bowhunt, and Judd was armed with one of the bows I make, a Kodiak model with a pull of 65 to 70 pounds.

Judd had used every precaution, even kicking his boots off and walking in his socks part of the time. But when we saw him close in to 25 yards, Judd could see only the bull’s neck. So he waited for a sure chance to put an arrow into the rib cage. While he waited, he felt a stray puff of wind catch him from behind and chill the sweat on the back of his neck. That was all the warning the moose needed.

“Never mind,” Judd said cheerfully. “I’ll do better at Devils Lake.”

WE WERE AFTER moose, goats, Dall sheep, and grizzlies. We’d left our take-off point on Haines Highway, 93 miles from Haines Junction, on Sunday morning, August 26, 1956. It was now the 31st, and our camp was set up on Blanchard Lake in Yukon Territory, a few miles north of the British Columbia border and about 50 miles east of Alaska. This area is good for goats and moose, fair for sheep and bears.

There were seven in our party, not counting Tiger, the young husky that Alex had brought along to keep grizzlies out of the cook tent. Judd (Dr. Judd Grindell, a bowhunter of vast experience from Siren, Wisconsin) and I were the hunters. Don Redinger, Pittsburgh photographer, had come along in the hope of doing something I’d wanted to do for 17 years—take good action pictures of a big-game bowhunt. Don was using a movie camera with a series of telephoto lenses and had his hands too full to do any hunting. (Don is the cameraman who, a few months later, went to Africa with the Texas sportsman, Bill Negley, to film the shooting of two elephants with a bow, the hunt that won a $10,000 bet.)

In addition to guides Alex Van Bibber and George John, we had a wrangler and a cook. Ed Merriam, the cook, came originally from some place in Virginia but like the Yukon better. Joe House, the wrangler, had quit a $2-an-hour job in town to shag horses, at considerably less pay, for the same reason. He liked it.

About the only time Joe had ever regretted the deal, he said, was on the hunt before ours, when he went out for the horses at dawn one frosty morning and blundered into a sow grizzly with two cubs. She jumped him, and Joe lit out with his hair standing up. Coming to a steep bank, he saw one of the horses at the bottom of it—directly below him—and made a flying leap stride, only to find the horse was one he’d hobbled the night before. Luckily for both Joe and the horse, the bear gave up at the top of the bank. Joe bought himself a rifle the next time he got to town, and now carried it faithfully.

We had 21 horses in our string and they were about as entertaining and companionable as so many humans. Each horse had a buddy, and we had to be careful not to separate pals in choosing animals for a side trip.

Alex has the best horses of any outfitter I ever hunted with. He keeps around 60, building up his stock from time to time from the wild-horse herds that still roam the Yukon. In spite of that, plus the fact that Alex pulls their shoes after the last hunt in the fall and turns the whole bunch out to shift for themselves until early summer, the horses are unusually gentle. The one I rode, Buck, used to stand over me half asleep while I sat on the ground and leaned against his front legs while writing notes on the day’s hunt.

Besides the fun that goes with every big-game hunt, this trip had a twofold purpose for me. Most of all I hoped to kill a grizzly bear with an arrow, something I’d dreamed of for years. If I succeeded I’d be the first man, so far as I knew, to take a full-grown silvertip that way since Art Young and Saxton Pope did it in Yellowstone in the early 1920’s while hunting down a big trouble-making bear under permit.

On top of wanting to take a grizzly this way, I wanted to test a new type of hunting point I’d recently developed for my arrows—a razorhead, a single-bladed broadhead that mounts and extra removable two-edged razor blade, very thin and hard, to do its cutting. We’d experimented with it for three years at my archery plant at Grayling, Michigan, and I’d killed antelope and other thin-skinned game with it in Africa. I was eager to test it on something bigger and tougher. That’s why my bow quiver now held three hollow-glass shafts mounted with these new heads, and I also had a reserve supply. Given the chance, I intended to find out just what the razorhead would do.

My bow was a Kodiak model, like Judd’s, with a draw weight of 65 pounds. Made with a hard-maple core, faced and backed with Fiberglas, these bows shrug off heat, cold, or moisture, and cast an arrow with great power and speed. So far as equipment was concerned, I was ready for business. The rest would be up to the grizzlies and to me, if the right time came.

THE HUNT was off to a good start. Before we left the highway we’d had some first-rate fun with grayling at Aishihik Lake, and I’d put in a lively morning shooting 30 to 40-pound salmon with harpoon arrows. That’s fishing to write home about.

Though neither Judd nor I had had a shot at big game in the six days we’d been out, we had seen plenty of sheep, moose, and goats (just couldn’t get close enough) and enough grizzly tracks to put any hunter in a hopeful frame of mind. Alex had wound up a successful hunt with another party a few days before, and everything looked rosy for us.

There was just one small fly in the ointment. I knew from the outset that Alex Van Bibber didn’t relish the idea of guiding a bowman, and he cared even less for guiding a bowman followed by a photographer. He had made that clear in advance.

Alex had his reasons, and I admitted they were sound. The average Yukon and Alaska guide figures to put his hunter within 200 yards of a grizzly or brown bear, and the rest is up to the client. If he can’t connect with a modern rifle at that range, he doesn’t deserve the trophy. If conditions warrant, the guide will move him in to, say, 100 yards. That’s about the limit.

Alex understood before we left Champagne that he’d have to get me a lot closer than that. I stopped killing game with rifles 25 years ago; the bow has been my sole hunting weapon since. Whatever I nailed on this trip, grizzly included, would be put down with an arrow. I had no intention of risking a bad shot at a range of more than 50 yards, and 25 or 30 would be more to my liking. The bow, however good it is, is not a long-range weapon. At 25 yards, a hurt grizzly can spell bad trouble if he’s not killed in his tracks, and that’s something no arrow—however well placed—can be expected to do.

He knew this and didn’t like it. It wasn’t a question of physical courage with him. He’s anything but short on that. His father was a mountain man from Virginia who went to the Yukon many years ago and cut enough of a swath that his name is still legendary up there. Alex is one of 12 children raised in the bush and schooled in the business of living off the land with whatever equipment they could put together. He was brought up to be afraid of nothing.

It wasn’t fear of bears that was bothering Alex. It was worry that his reputation as a guide might suffer if things went wrong. For one thing, when you have to stalk as close as you do in bowhunting, there’s always a chance of spooking game and losing the best trophy of the hunt, maybe after weeks of waiting and working for it. For another, Alex felt he’d be in a bad spot if he should lose a hunter—even a crazy bowman—to a wounded bear.

I didn’t much blame him when he said to me while sipping a screwdriver—an odd drink for a leather-faced Yukon guide, but his favorite—before the hunt started, “I’ll see it through and do the best I can for you, but I wish you were using rifles instead.” There was no chance of that.

The day after Judd missed getting the big moose, we broke camp for a two-day ride to Devils Lake. Ten days of rain and snow had soaked the mountain tundra like a sponge. The alders and scrub willow dripped as we rode through them, and the weather wasn’t getting any better. In five weeks we were to see just five days of sunshine.

Base camp at Devils Lake turned into little more than a place to pick up supplies. With good rain gear and dry bedrolls, we roamed the country in the saddle. My rainsuit is a two-piece outfit of coated nylon, so tough it’s almost indestructible and so waterproof I can sit in a pool for hours without getting damp.

Good rain gear came in mighty handy hunting the Devils Lake area. We made side camps and stayed in them for a day or two at a time, hunting in rain, snow, and fog. Many days when we rode high we could see clear weather in the distance, but all of Alaska to the west seemed to be funneling wind and water our way. We saw no bears.

Now and then we saw a moose, but never close enough for a shot, and though goats were fairly plentiful we had no luck stalking them. Except for the lower lakes and valleys, the country was all above timberline.

We hunted canyons, climbed vertical cliffs, waded glacier-fed rivers. We stalked one good billy to within 100 yards on an open plateau, then ran out of cover. He might as well have been on the moon.

But we were finding plenty of small game, getting enough shooting for practice, and having a fine time. Ptarmigan were plentiful and made a welcome addition to our grub list, but were hard on arrows because of their habit of squatting among rocks.

Shooting a bow hunting-style is done instinctively, without sights or mechanical aids, and daily practice is necessary to keep in form. We were using blunt arrows for small game and target work, and after a week I’d broken so many heads that my supply ran out. We found a way to repair them by filing off the necks of empty .30/06 cases so they fitted over the broken shafts. Spruce gum in the cases, heated over a fire, made a fine bonding agent.

The big blue grouse down in the scrub timber were tame enough to be a bowman’s delight, and fine eating too. A couple times we even varied our menu with fresh grayling.

Our only contact with the rest of the world was a bush plane that dropped supplies and mail, including a letter for Alex from his wife, with the latest news from Champagne. A native had lost his entire dog team to a grizzly that wandered into his cabin while he was away for the day. When he came home after dark and went to look after his dogs, the bear came within an inch of clobbering him. Wolves had all but killed a mare and colt belonging to Alex, but Mrs. Van Bibber had sewed them up and through they’d recover. It seems there are plenty of things to worry about, even up in the Yukon.

At the end of two tough and weary days out of base camp, we finally got a day of blue sky and sunshine. From our side camp on Upper Hendon Lake, right after breakfast that morning, Alex and I spotted three goats—two billies and a nanny—high on the mountain above camp. One billy looked very good, and we voted to make the hike.

It took us three hours to climb to them. By then they were bedded on a bench in the open, so we holed up behind a rock 500 yards away to wait them out. Below us, the Hendon River snaked through a long, narrow willow flat.

We stayed hidden, peering over the rock from time to time, until late afternoon. Finally the goats moved off to feed, and as soon as they were out of sight we started after them. A steep side canyon was in our way. We clambered down into it, waded a brawling snow-melt creek in the bottom, and started up again. Suddenly Alex grabbed my arm and pointed ahead. Above a shelf 30 yards away, I saw the black tips of a goat’s horns. I laid an arrow on the string and inched my way up toward the shelf, walking as light-footed as a cat.

Most men who knock over a mountain goat with a rifle feel they’ve taken one of the toughest-to-get trophies in North America, and nine times out of 10 they’ve good cause to think so. Mr. Whiskers rarely comes easy. I’d certainly worked hard for this one, but the wind was right at last and the footing good.

Now, only 20 yards from the black-tipped horns, I was climbing slowly and warily, hoping to see the billy’s body before he saw me. Suddenly gravel crunched underfoot, and up on the shelf three goats came to their feet like big white jumping jacks. I’d caught the two billies and the nanny flat-footed—at closer range than I’d dared to hope.

They stood broadside, staring in amazement, as if not believing a man could get that close.

I didn’t give them time to collect their wits. Even while I was taking in the picture, I was pulling the bowstring back into the angle of jaw and throat. Before any of the three twitched a muscle, my arrow was on its way.

I’d picked the biggest billy, and my razorhead slashed into him diagonally—a little too far back for the lungs. It sliced all the way through, came out his flank, and sailed off down the canyon. The other two goats went out of sight in a couple of jumps. Mine flinched, pivoted, and started away, running over tumbled boulders. My second shot missed him at about 50 yards, but the third, released as fast as I could nock and draw, knifed up under a shoulder blade. The goat turned downhill, running heavily, and disappeared in a side canyon.

When we found him he was lying at the edge of a ledge. I put another arrow into his back to finish him. But there was no way we could get down to him without ropes, and it was too near dark for us to fool around on the mountain. Unless we got off immediately, we’d have to spend the night there. So we headed for camp.

It was pitch dark when we got there. The river had risen a foot or more during the day, as a result of the glaciers melting in the sun, and we got wet fording it. I was bone tired, but felt pretty good.

Right after breakfast next morning, we started back up the mountain with ropes. “Better take your handgun along,” Alex suggested. “If a grizzly found your goat, you might need it.” That sounded like good advice, so I followed it.

When we got to the goat we found he’d kicked himself off the ledge and was lying dead in thick alders in a draw below. Fortunately he hadn’t broken his horns. He was a good billy, around 200 pounds, with 9 ½-inch horns, just what I wanted for a full mount in my trophy room.

When we skinned him, we found that my first arrow had put him out of business. Striking too far back for either heart or lungs, it had gone through the diaphragm and stomach and cut him up enough to bleed him to death quickly.

We rolled the head, ribs, and a front quarter in the skin, stuffed it into a packsack, and started to hike to camp. With the camera gear, we had a sizable load. Alex and I traded packs from time to time. We got to the river past noon and edged across on stepping stones, bracing ourselves with stout poles against the rushing, milky current. By the time we reached camp it was too late to make another trip for meat that day. The following morning we climbed the mountain again and brought down the remaining quarters.

I’d never intended to tackle a grizzly with the bow alone, unbacked by a rifleman. While I have complete confidence in the killing power of a well-placed arrow, I also know that an arrow-shot bear isn’t likely to die then and there.

Two days later wer rode into base camp in wind and rain and got a warm welcome. Up to now our meat supply had depended mostly on what was left of a moose that had been killed on a hunt Alex handled earlier. That was about gone, and fresh goat looked good to everybody.

Judd and George John came in that night with the pelt of a good blond grizzly, but Judd wasn’t satisfied with his kill. They’d stalked the bear to within 150 yards, and then the guide flatly refused to go closer.

George John has a powerful phobia where grizzlies are concerned, and carries some bad scars on his neck, arm, and shoulder to prove its no idle whim. He had a tight shave on a hunt a few years back, when he tackled a grizzly at close range with a .30/30. The bear grabbed him by a shoulder and came close to killing him before his hunting partner got a shot into its head. George John simply won’t go near a grizzly now if he can help it, and he regarded my determination to take one with a bow as downright foolish. Nothing Judd said could make him go closer.

Judd’s time was running out (his hunt was shorter than mine by three weeks) and he figured this was the only chance he’d get. The thought of that blond bear pelt on the floor of his study was too much to resist, so he reluctantly asked George John for the loan of his rifle, a 6.5mm Mannlicher. When the guide handed it over, Judd asked how it shot at 150 yards.

“Dunno,” George John grunted. “Not my gun. Borrowed from cook.”

Apparently the sights were O.K., because Judd nailed the bear through the heart and anchored it almost in its tracks.

A COUPLE OF DAYS after Judd killed his bear, we stopped for lunch beside a small glacial stream in a pretty little valley. Cold rain was falling but Alex produced a stub of candle, flattened and dark from much carrying in his pocket. He lighted it and held it under a pyramid of wet twigs that dried slowly and finally crackled into a brisk, small fire that licked cheerfully up the blackened sides of our tea-water pail.

We ate cold goat and Yukon doughnuts for lunch, and the stop was pleasant in spite of the weather. The last drop of tea was gone and Alex was stamping out the fire when he happened to look toward a mountain half a mile up the valley, and spotted a bear working down a steep slope.

He lifted his glasses for a quick look. “Black,” he announced. Everybody looked and agreed. Nothing to get excited about, even though it was a big one. However we may feel about black bears in the States, in Alaska and the Yukon they’re regarded by guides and hunters with about the same contempt that trout fishermen feel for suckers.

We stood there for 20 minutes, watching this fellow amble down off the mountain. He took his time, stopping every now and then to dig, but finally he worked his way into a patch of willows and disappeared. We climbed into our saddles.

Our course upvalley led along the foot of the mountain, about a quarter of a mile from where we’d last seen the bear. As we rode, I kept turning the situation over in my mind. The more I thought about it, the more unwilling I was to pass him up. He was the first bear I had been close to on the hunt, and big enough to rate as a good trophy. And he’d given me a chance to try my razorheads on tough, thick-skinned game. I knew the guides wouldn’t bother with him unless I insisted. Alex hadn’t promised to hunt blacks. But I decided to insist.

Just at that point we topped a low rise and saw him again. He was on the side of a ridge across the creek, and while we watched he walked down into a draw, out of sight.

“What do you say?” I asked Judd. “A bear is a bear,” he replied. “Let’s go get him.”

We climbed out of our saddles, stripped off our rain gear and chaps, and started for the ridge. Don un-limbered his movie camera and trailed us. Alex and George John stayed on their horses, watching with tolerant grins.

Our position as we approached the ridge put Judd on my right. He’d climb that side and I’d circle around the opposite slope, about where we’d last seen the bear. I rounded the end of a low knoll, and there he was, digging out a marmot less than 100 yards away.

His front legs were down to the shoulders in a hole he’d excavated, and he was trying to watch all sides so the marmot wouldn’t pop out and get away. His rump was toward me, so it was easy to back off, crouch down, then creep up behind a small boulder just 25 yards behind him. I made it without attracting his attention, and with my arrow on the string, I rose in a half crouch on one knee. But before I could draw, the bear jerked his head around my way, still looking for the marmot.

Now, for the first time, I noticed a telltale sprinkle of gray hairs in his rain-wet pelt. I’d have seen them sooner in dry weather. This was no black bear. This was what I had come to the Yukon to kill—but the circumstances were anything but what I’d planned. I was all alone and looking into the grizzled, bulldog face of a silvertip just 75 feet away.

I’d never intended to tackle a grizzly with the bow alone, unbacked by a rifleman. Alex and I had a clear understanding on that. While I have complete confidence in the killing power of a well-placed arrow, I also know that an arrow-shot bear isn’t likely to die then and there.

What I faced now as a lot more than I’d bargained for. I’d even gone to considerable pains to make sure it didn’t happen. To begin with, Alex has a good reputation as a rifleman and it was agreed he’d be behind me with his .30/06 any time I got close to a grizzly. But now he was sitting in his saddle on the other side of the creek.

I hadn’t wanted to get into any such spot as this without a handgun either. When I started planning a grizzly hunt, I bought a .44 Magnum Smith & Wesson revolver and put in a whole summer of practice with it. The Canadian Government and the Mounties at Whitehorse had been co-operative about giving me a permit to carry it on the hunt, just as Them Kjar, Yukon game commissioner, had readily given Alex an O.K. for carrying a rifle while guiding bowmen. The Yukon authorities didn’t want an accident on this bear hunt any more than we did.

But my Smith & Wesson was heavy in its shoulder holster and interfered with the use of the bow, so I had formed the habit of carrying it in another holster on my saddle. It was back there now, with Alex and my horse. I was on my own all the way, no matter what happened.

It was a tough challenge but it was also the chance of a lifetime, and it seemed pretty late to back out. I don’t think I weighed it for more than three for four seconds—just long enough to tell myself that if the grizzly charged me, he’d be running downhill and I’d have time to dodge once and get a second arrow into him. Thirty seconds later I was doing some tall wondering on that score.

Still crouched behind the boulder that was barely big enough to break my outline, I brought the string back and let drive. I didn’t know it at the time, but Don Redinger had come up behind me within 150 yards and was covering the whole affair with his camera. The movie film later showed exactly what happened, in even clearer detail than I recalled.

The bear heard the twang of the bowstring and I saw his head jerk around in one of those lightning-quick moves any bear can make. But before he could locate me, the arrow slashed into his rib section.

He growled and whipped sidewise, snapping at his side where the arrow came out. It had knifed all the way through him, slicing off a rib and cutting through lungs, diaphragm, liver, and intestines, and still had drive enough to bury itself above the head in the hillside.

The grizzly bit at his side while I could have counted three. Then he swung around, hesitated a moment, and came for me, growling and bawling. I got ready to dodge. But the way he was barreling, I was no longer sure I’d have a chance to use a second arrow.

Then he did a thing I’ll never understand. Maybe he changed his mind in mid-charge or simply failed to locate the cause of his trouble. Bears are notoriously nearsighted, and maybe that was what turned him. I can think of no other good reason why he shouldn’t have kept coming.

But he didn’t. Halfway to me, he swerved up over the ridge. Judd saw him come down the other side. The grizzly spun around two or three times in tight circles, and went down to stay. We paced it off later. After the arrow hit him, the grizzly ran 80 yards before he dropped.

THIS WAS my 50th kill of big game with a bow, in the United States, Canada, Alaska, and Africa. I’d dreamed of a grizzly for years, and when I found that Don had photographed the whole thing with the six-inch lens on his movie camera, I was about as happy as a hunter can get. As things turned out, I was fated to share honors with Bill Mastrangel of Phoenix, Arizona. He reported killing a good grizzly with a bow in British Columbia in September, shortly after the hunt I’m telling you about.

My bear was no monster, but he was big enough to satisfy me. Gaunt and thin, but with massive head and shoulders, he had the powerful legs and typical long claws of the silvertip. These mountain grizzlies don’t grow as big as their fish-eating cousins at the seaside. But considering location and food supply, this was a good bear, and when we got his pelt off we uncovered a streamline carcass that was all muscle and sinew.

Most of the time it’s these medium-size ones, not the big bruisers, that make trouble for a hunter. The big ones know better. Bears like mine are the bad boys—the cocky young toughs. George John remarked that mine was almost exactly the size of the one that had mauled him, and Alex added that it was a bear in about the same class that had killed a hunter in the area only a year or so before.

When we opened this grizzly up to see what the arrow had done, we found a hole in his diaphragm so big that the stomach had jostled through it into the lung cavity as he ran. He had bled white inside from the cuts made when the razorhead slashed through his vitals.

Bad weather continued to pile in, winding up in a sharp temperature drop and an eight-inch snowfall. Judd left for home, flying out from Devils Lake. Alex and I rode a lot, hunted hard, and saw plenty of sheep and moose, but we couldn’t make connections. We could have filled my license many times with a rifle. However, I can’t say I was disappointed when we rode out to Champagne in the teeth of a bitterly cold wind the last day of September. I figure a goat and a grizzly on one trip are about all a bowman should ask for, and on top of that I’d had a couple of nice demonstrations of what the razorhead will do.

Quite a few times since the hunt, I’ve been asked whether I’d tackle the grizzly single-handed-with the bow alone, if I had to do it over again. That’s a tough question.

Certainly I wouldn’t recommend that any hunter try it deliberately. Remember, I didn’t do it intentionally. But if I had the same chance again, in the same circumstances—and especially if I was above the bear with a rock or cover of some kind to duck down behind after releasing my arrow—I’d have to make the same decision. I guess that’s the way it is when you’re after trophy game.

Read more OL+ stories.