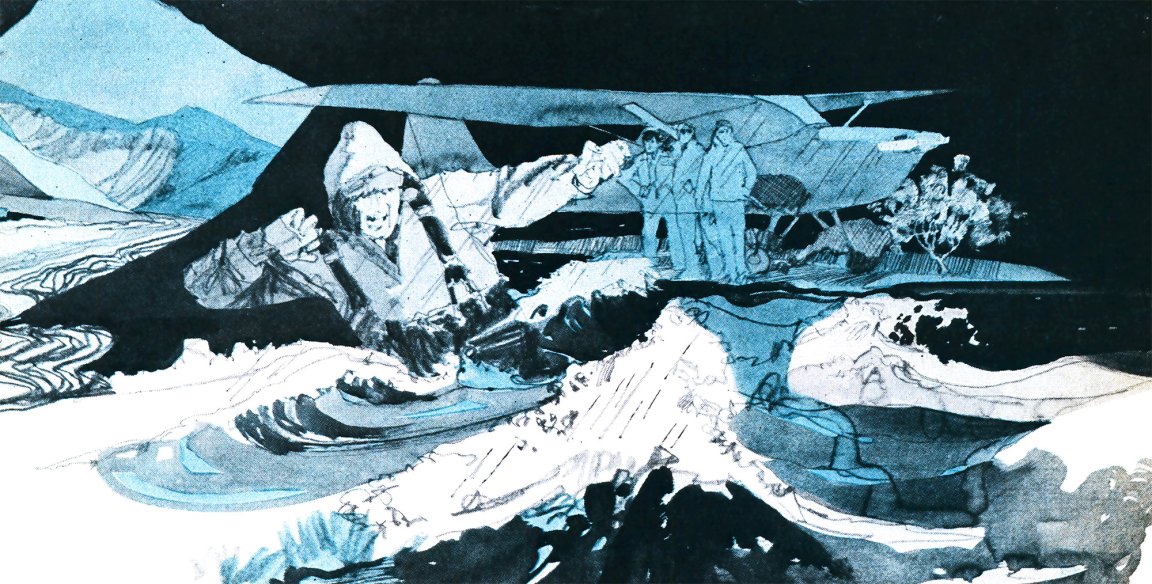

There were four of us. Right after sunrise we had done an almost unbelievable thing. Within the space of a minute, we had killed four good moose, no farther than rifle range from our tents.

We were packing the quarters the short distance into camp when the trouble started.

The weather had been good for several days, as weather goes on the Alaska Peninsula, but then heavy dark clouds began to roll into our mountain valley from Yantarni Bay, an arm of the north Pacific only five air miles away.

We couldn’t fly out in that kind of murk, but we felt no concern. We had to stay in camp another day anyway to bone out our meat and level a longer runway for the takeoff. By the time we were ready, we agreed, the weather would clear. That was a bad guess.

We had a good supper of moose tenderloin and cornbread, and by the time we finished, we were socked in by dense clouds that hid everything more than 100 yards away.

We slept in our two small tents, and we slept badly. Wind-driven rain slashed against the tents all night, and the one Larry Haddock and I occupied leaked so badly that we were soaked in spite of our sleeping bags.

We crawled out at the first hint of daylight, too wet and wretched to stay longer in the soggy bags. It was a gray and cheerless morning with clouds enveloping everything around us. rain still pouring down, and wind raging across our gravel bar.

Lee Wimmer and Roland Haycock had spent the night in a brand-new tent, but it leaked even worse than Larry’s and mine, and our two partners and all their gear were drenched.

We spotted six bull moose within a mile, and we turned in that night telling ourselves that the next day would be spent butchering and packing meat.

The first things we found in the growing daylight were wolf tracks all around the tents and our piles of meat. It was proof of something we already knew — that we were in a virgin valley where humans came very rarely, if at all. In all likelihood those wolves had never encountered man before. They had come within three feet of where we were trying to sleep, so recently that there had not been time enough for the rain to wash out their tracks.

“I swear I heard them prowling,” Larry told us. “I even heard one yawn.”

We ate a wet breakfast and went at the job of boning and cutting up the moose meat. But the weather was so bad that we made little headway, and we finally gave up, covered the huge pile of quarters as best we could, and took shelter for the rest of the day in the cramped quarters of our plane.

We left it only once that day. The storm seemed to subside a bit, and we draped a small canvas over one wing for a windbreak and cooked a skimpy meal over our small primus stove.

The hunt had begun on August 17, 1974, when Haycock and Wimmer and I left Provo, Utah, for Anchorage in Roland’s four-place Maule, a powerful, bush-type, workhorse aircraft.

All three of us were family men with patient wives and children. Roland was an insurance man from Pleasant Grove, Utah, 35 at the time. Lee, 29, was a consulting engineer from the same town. I was 37 with a wife and three sons and a daughter between four and 13. I’m a resource specialist with the Bureau of Land Management, and I was stationed at Monticello, Utah. I have since been transferred to Pinedale, Wyoming, where we now live.

Roland and Lee had not been in Alaska before, but I had been stationed for a time at Delta Junction, and so was familiar with the fabulous wild country we were heading for.

The three of us had gotten together in an unusual fashion. I had made a hunt in Alaska in 1971 with four partners. We used a privately owned aircraft. It turned out very well, and I was eager to repeat it if I could find someone to supply transportation. I sent out posters to four or five local airfields. asking any plane owner who was interested to contact me, and offering to set up all the arrangements for the hunt. Haycock and Wimmer replied and came to my home in Monticello to get acquainted, and the trip took shape. Roland’s Maule was just what we needed.

Our wives, normally sympathetic about our hunting trips, were anything but enthusiastic this time. Even Roland’s wife was worried, despite the fact that he owned the plane and had logged many hours in the air.

“There’s something about this one I don’t like,” she said.

We planned to make the flight to Anchorage in two days by way of Great Falls, Lethbridge, and Fort St. John, but it took four days because of delays at Canadian airports to wait out bad weather, a mere foretaste of what was to come

At Anchorage the fourth member of the party, Larry Haddock, met us at the airfield. Larry was my age, and he and I were friends from our student years at Utah State University. He and his wife and four children had been living in Anchorage for four years while he worked as a pilot and biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The next morning we took off for King Salmon, a small Air Force base and hunting-and-fishing village Bristol Bay on the north side of Alaska Peninsula. Located on the doorstep of wild and rugged country, King Salmon serves regularly as a refueling stop for hunting parties and as a place to get information on the location and abundance of game.

We talked with the right people and decided to try Painter Creek, an area about 100 miles to the southwest, where King Salmon residents thought we’d find moose and caribou. The easy flight was across flat tundra and lake country, and we landed on a good gravel airstrip on a foothill ridge. It had been built as part of an oil-exploration effort at some time in the past.

We did not have the place to ourselves. Five men were exploring for oil nearby, and they were using the airstrip and living in a corrugated-metal cabin. And another hunting party was there — two men from Arkansas, who had flown in by charter service. But the country was big enough for all of us, and they made us welcome. They hunted one way out of camp; we went another.

We hunted hard for three days and saw many tracks of moose and caribou, but not one of the animals. The tracks were old, and we concluded the helicopter activity had driven the moose out of the area, and the caribou had not yet moved down from the high mountains.

Our only bit of luck came the first morning, when I killed a wolf that came trotting past us upwind, only 100 feet away. Thick brush screened us, and the shot was an easy one. The wolf, a barren bitch, dropped at my shot and began tearing at the wound. She instantaneously disemboweled herself with two or three slashes of her teeth and severed all the ribs in the lower left chest before she died.

“That’s not a pretty picture,” someone remarked as we looked down at her. Indeed it wasn’t. The pelt was almost useless.

One thing we did have at Painter Creek was fabulous fishing for sockeye salmon and Dolly Varden trout. They took our spinners and wobblers ravenously, and we threw back too many fish to count. The trout weighed three pounds to seven; the sockeyes five to eight pounds.

At the end of three days we decided to try another location. The pilot of the oil-crew helicopter had told us of valleys on the other side of a nearby mountain range that were overrun with big bull moose and caribou. The place was only about 10 miles away in a direct line, but because the mountain passes were hidden in ground fog and low clouds, we had to go around the end of the range at Port Heiden and then turn inland and come back to our destination. We thought the pilot’s reports might be greener-on-the-other-side tales. But we had nothing to lose, so we took off early on the morning of the fourth day.

We turned inland from Port Heiden and flew almost all the way across the Peninsula to within five miles of the south coast, following the west side of a chain of mountains. And as we neared the Pacific we began to see the game we had been told about.

We flew over a big river, and below us brown-bear sows with cubs were fishing for salmon. Moose were plentiful, feeding and resting on grassy knolls. Curiously enough, there were no cow moose that we could see. All bulls, and many had racks that appeared to be in the record-book class. It was a wonderful game area, we agreed.

The one problem was finding a place to set the Maule down. The only possibilities were on rocky, gravel-bar floodplains. We finally chose what looked like a level spot in a valley.

Because Larry Haddock was an experienced pilot and familiar with conditions in Alaska, he and Roland were alternating at the controls of the aircraft. Larry was flying it when we chose our landing place. He brought us in for a bumpy landing. We paced the gravel bar and found it was only 325 feet long, bracketed on both sides by deep, dry stream channels. We knew that if we killed moose, we’d have to find or build a longer strip to get airborne with a load of meat.

Camp was quickly set up. It consisted of two small backpack tents and a tiny primus stove. The stream itself flowed past 50 yards away. It was beautiful and clear, only 30 feet wide, and three or four feet deep. That it could fill its delta, half a mile wide, did not even occur to us at that season of the year.

Alders and high grass grew to the edge of the floodplain on both sides, but nearer the camp there were water-polished rocks, gravel, and sand. Only a few alders had managed to find a toehold. We moved the plane to a place between two of the alder clumps and tied the wings down as securely as we possibly could.

Alaska game laws forbid taking big game until after midnight of any day the hunter is airborne, so we put in our first afternoon scouting the valley. We spotted six bull moose within a mile, and we turned in that night telling ourselves that the next day would be spent butchering and packing meat.

When we crawled out of the tents the next morning, four big bull moose were feeding in plain sight within rifle range. We made a short stalk through thick brush and put ourselves within 75 yards of two of them. The other two were 50 yards farther off, above and a little to the right of the others.

All the heads looked good, so the man on the left took the moose on the left, and so on. We fired together, and four shots filled four moose licenses. It was an extraordinary kill, and I would not like to see it repeated too often, but as every hunter knows, sometimes you spend weeks in the bush without getting a shot. The smallest animal had a rack that spread 55 inches; the largest went 66.

The sport of the hunt was over when we pulled our triggers, and the discomfort, work, and the storm began, as I related at the beginning of this story.

The storm began on Monday, August 26. We spent that night in the tents, and we were very wet and miserable. For the second night, Larry and I added a light canvas cover to our tent and tried it again. Roland’s and Lee’s sleeping bags were lying in three or four inches of water inside their tent, and they elected to huddle in the plane.

A small worry nagged at us that night. We had filed a flight plan at King Salmon, which listed our return for 6 p.m. that day. We were overdue, and because of the mountains around us, there was no way to use the radio to report our situation. We knew that the Federal Aviation Agency had surely launched a telephone search to determine if anyone had seen us or knew our whereabouts. The agency would be putting rescue planes in the air the first thing in the morning, if the weather permitted. Worst of all, our wives would be notified that we were missing, and it was easy to imagine their anxiety.

All that was bad enough, but we were to have more serious worries in the next 24 hours.

Things grew worse that Tuesday night, and unendurable weather drove us into the plane at daybreak on Wednesday. By then the cloud cover was so thick that we could barely see the wingtips.

We tried that day to raise Kodiak on the plane’s radio but had no success. Larry also knew the flight schedule of a Reeves Airline plane from Port Moller to Anchorage. When he thought the flight would be over our area, we tried calling the pilot every few minutes. We even tried calling stations at random, hoping to be picked up by a passing ship. Only lonely silence rewarded our efforts.

About 2 a.m. Larry and I were awakened by a raging wind that threatened to blow the tent away. We crawled out to find our two partners trying desperately to anchor the plane more securely. It was bouncing up and down like a live thing. If we lost it, we would be in the worst kind of danger.

That Wednesday night, Larry and I went back to our leaky tent once more, while Roland and Lee took to the Maule and tried to sleep with their knees under their chins.

About 2 a.m. Larry and I were awakened by a raging wind that threatened to blow the tent away. We crawled out to find our two partners trying desperately to anchor the plane more securely. It was bouncing up and down like a live thing. If we lost it, we would be in the worst kind of danger. We placed two hindquarters of moose over the wheels, put two more on the struts where they joined the fuselage — one on either side — and hung one from the tiedown ring on each wing. Those quarters weighed not less than 150 pounds apiece. The six of them added almost half a ton to the weight of the Maule.

On Thursday the wind rose in screaming fury and blew sheets of rain horizontally across our gravel bar. We learned later that it blew 70 miles an hour most of that day, and the four of us jammed into the plane, hoping our weight would help to hold it down.

Just about the most-surprising thing that happened during our ordeal was that the wolves came up to our very tent flap every night in spite of the dreadful weather. We found their fresh tracks each morning. Evidently wolves hunt when they need to do so.

We used our radio sparingly that day, fearful of running the battery down, but got no answer. Several times we imagined we heard aircraft above the howling of the wind, but when the sound did not change direction. we knew it was only an illusion.

Things reached a frightening climax that afternoon. Lee climbed out of the plane. Then he popped his head back in the door and yelled that our tents were flooding.

We piled out and got a real shock. Our clear, 30-foot-wide river had risen to a raging torrent that filled the floodplain from side to side. The tents were flapping about in two or three feet of water. Every channel we could see was bank-full, and logs and uprooted alders swept past, rolling and tumbling in the yellow-brown torrent.

We waded in to salvage the tents and equipment. Our cased rifles would never be the same again, and the river was rising so fast that we could see it creeping up on our gravel bar.

We spent a sleepless Thursday night in the plane. The storm raged unabated, and our fears continued to mount. Visibility was still zero Friday morning, and the entire river delta was flooded, except for the tiny gravel-bar island where we had landed. The rising water lapped at the wheels of the plane. Our big pile of moose quarters and boned meat in burlap bags was hidden under the murky flood waters somewhere.

That morning we debated whether we should abandon the plane and try to wade or swim to the nearest high ground.

“We won’t know if we don’t try,” Larry finally said.

He put on boots and stepped into the current, but he had waded no more than five feet when the raging river all but carried him off his feet, and we saw that it was suicide to leave the gravel bar.

We inflated our air mattresses to serve as rafts in case the plane was washed away, and waited helplessly for whatever might come. Prayers aplenty went up from our little island, and when we decided we were within an hour of final disaster, they were answered. The rain stopped for the first time since Monday, and the wind dropped to a breeze. Within an hour the flood waters began to inch down.

By Friday evening the clouds had lifted enough so that we could see 500 yards up the nearest hillside. The first thing we sighted was a big bull moose bedded on a wooded ridge.

Saturday morning brought heavy cloud cover but no rain, and the river had dropped enough to uncover our pile of meat. Our supply of other food had been gone for two days, and we celebrated in a hurry with a moose cookout.

Another meat-eater had been at work during the night. Where we had seen the bedded moose the evening before, a very large brown bear was feeding on a moose carcass. Apparently he had bushwhacked the bull during the night and was enjoying his reward. He was so close that we kept a watchful eye on him too.

Related: The Top Moose Cartridges and Bullets

Early that afternoon, the sixth of our ordeal, we heard the steady drone of an ai re raft in the clouds along the seacoast. This time it was no illusion. The sound was moving, and Larry raced for our plane and turned on the emergency transmitter.

We were sure the aircraft was searching for us, and we were right. It changed course almost instantly and turned inland. The pilot was flying a grid pattern, homing on our signals.

When he was close enough, although still hidden in the clouds, Larry went on our radio. The voice that answered moved all four of us to tears. It belonged to an Alaska state trooper, flying as part of the search effort that had been under way for four days. The search was pressed by the Federal Aviation Administration, the Civil Air Patrol, the Coast Guard, and Air Force planes out of Elmendorf Base at Anchorage.

“I was almost blown out of the air when I tried to get into this area yesterday,” the pilot told us. “I still can’t make it through to your side of the range, but the forecast is for clearing weather tomorrow. You’ll be out by noon.”

We had never heard better news. If it turned out that he was right, our fears and worries were over.

Four good trophy racks are probably still lying on that remote gravel bar, but we have no intention of going back to reclaim them.

Sunday morning dawned with a high overcast. After a week, we could finally see the mountains around us. We worked all that forenoon to ready a takeoff runway on a longer gravel bar. We cleared rocks away and filled small flood-created gullies with sand and gravel.

About noon Larry gunned the Maule — heavily loaded with moose meat — to a heart-stopping takeoff from the makeshift strip. He cleared the scattered alders by a few feet and headed for Port Heiden.

It took three trips, each marked by a hazardous takeoff and landing, to ferry out the 657 pounds of meat we were able to salvage, our equipment, and the four of us. The meat represented no more than a third of the total, maybe not even that. We had estimated the live weight of the four moose at 1,400 to 1,500 pounds apiece. Each man’s share came to nearly 500 pounds of boned meat. But the weather was warm, and the water-soaked chunks spoiled very quickly. They turned green and smelled foul. We had to cut away large pieces.

Four good trophy racks are probably still lying on that remote gravel bar, but we have no intention of going back to reclaim them.

We air-freighted our meat and gear from Port Heiden to Anchorage. On Monday, September 2, one day short of a full week overdue, we took off on our long flight home. News of missing men spreads like a brushfire in Alaska, and when we touched down at Pilot Point and King Salmon on the way to Anchorage, the control towers and then the local adults and kids greeted us as though we were men returning from the grave. They weren’t far wrong either.

Larry’s reunion with his wife and children at Anchorage was a joyful thing to watch, and the rest of us will never forget those phone calls to our families.

That should be the end of our story, but there is a tragic postscript. Just four weeks after we got back to Anchorage, Larry took off with three biologists in a twin-engine Grumman Mallard. It was a routine flight to Kodiak, where they were to begin a study and census of the teeming seabird colonies along the coast of the Gulf of Alaska.

Larry was not at the controls that day, but the pilot who was had flown in Alaska for 25 years. He was following an established route and hugging the beach too, but again Alaska’s weather took a hand. Snow blew in on raging winds, visibility and ceiling dropped to zero, and the Mallard was never seen again.

Read Next: How to Insult Your Western Hunting Guide

Scores of planes combed the coast and the sea for many days after the weather cleared, but the search was in vain. No trace was found of the four men or their aircraft.

I had lost one of my best friends and a treasured hunting companion. But for his coolness and skill with the Maule, Lee, and Roland and I do not believe we would have returned from our ill-starred hunt. I’ll say it simply. Larry Haddock was a good man.

But the storms that lash the unpeopled coasts and jagged mountains of our Fiftieth State are no respecters of men, even the best of us.

This story, Come Wolves and High Water, appeared in the March 1972 issue of Outdoor Life.