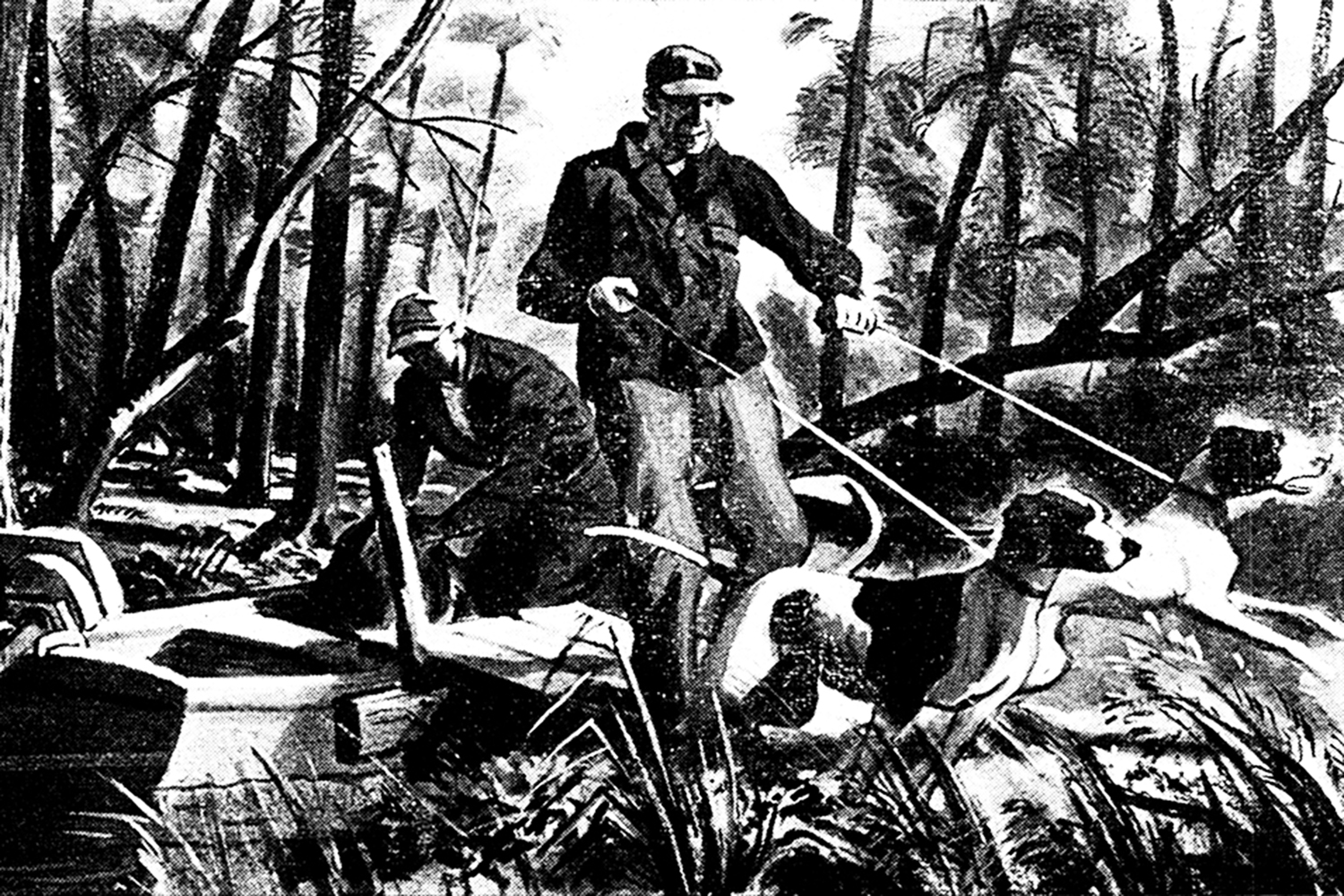

This story, “Bear Hunt in Dismal Swamp,” originally ran in the February 1946 issue of Outdoor Life. Although the author mentions potential protections for the Dismal Swamp, it wasn’t designated for conservation until 1974, when it became the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. At nearly 113,000 acres, the refuge is the largest intact remnant of a vast swamp that once covered more than one million acres of Virginia and North Carolina.

A BIG POTLICKER whimpered, then tilted its nose skyward and sounded off mournfully. The somber gaze of the half a dozen other hounds crowded in the bow of the boat had been held unswervingly on the bank, but now they all surged to one side of our overloaded skiff.

“Down, dogs–down!” Dave commanded, hauling back a neat-footed little bitch that was doing a tightrope-walking act on the gunwale. “Down! There are too many water moccasins in this ditch for comfort, if you should tip us over!”

The hounds subsided obediently on the floor boards, and the boat rocked back onto its flat bottom. Ed, who was steering, laughed and pointed to the clean-stripped branches of a black gum tree on the bank.

“Bear sign, and fresh,” he commented. “Been eatin’ berries. Last night, I reckon.”

A bear was what we were after in the forbidding Dismal Swamp of tide water Virginia. Lloyd, who started life on a California cattle ranch and still wears blue jeans when he goes hunting, wiped his hands on them and picked up his .30/30 Winchester.

“Too early now for the chance of a shot,” Dave discouraged him. “And anyhow, the outboard makes too much noise. But sometimes late in the evenin’, when it’s almost dark, you can sneak along in a row boat and shoot a bear out of a tree.”

“Shucks,” Ed said, “you don’t have to go sneakin’ round in a boat to shoot a bear out of a tree. Why, Mr. Cherry did that the other night out of his bedroom window. The bears have been bustin’ up his beehives somethin’ scandalous this year, and he’s provoked at ‘em.”

Before we go any further, let’s get ourselves oriented. Half an hour earlier Lloyd and I had kept a long-standing date with Dave and Ed at the general store at Wallaceton. That’s about 25 miles south of Norfolk on U.S. Route 17. For more than 30 miles the highway parallels the Dismal Swamp Canal—eastern border of the 700 square miles of marshy wilderness that sprawls over a sizable portion of two Virginia and five North Carolina counties.

At Wallaceton we loaded hounds, rifles, duffel, and ourselves into an ancient boat, Ed spun its outboard into action, and we headed up the feeder ditch which leads to mysterious Lake Drummond, hidden in the heart of the swamp.

Nowadays that narrow, straight-as-a-string channel of black water is the only route you can travel into the part of the swamp where the bears are thickest. It wasn’t always that way. In the days when cypress and cedar were being cut, the ditches which lead into Lake Drummond from the western side of the swamp were busy waterways, but now they are so barricaded by wind-toppled trees and so clogged by snake-infested aquatic growth that it is impossible to pole even a canoe through them.

No matter how many hunting trips you’ve made, there is a sense of taut-nerved expectancy on each new “going in” that sets your blood to circulating faster. And going in on this amphibious hunt was even more exciting than usual. It had a strong spice of novelty. Dismal Swamp is familiar hunting ground to Ed and Dave, but it was both new country and a new kind of country to Lloyd and me.

Best of all, we were going bear hunting! There’s always a thrill in that. Most Virginia bears, whether they live in the swamp or in the mountains, are rather on the small side, and maybe they are as big cowards as my friend Bob Lattimer, a Pennsylvania game protector, claims all black bears are, but they carry an armament of claws and fangs backed by brute power that makes them potentially dangerous game. No hunter who is interested in keeping his skin whole should ever make the mistake of thinking that he knows what a wounded or cornered bear is going to do next. Bear hunting always promises excitement—and not infrequently it produces it in quantity.

WHEN WE SAW that first bear sign we were still close enough to the highway to look back and see cars passing on it, but already the big swamp had walled us in with its weird silence. It was a warmish, windless day at the tail end of October, and except for the putt-putting of our outboard there was no sound.

And the swamp was as still as it was silent. There was no movement in the tangle of creeper-interlaced brush that covers the low banks of the feeder ditch; not a leaf shivered in the foliage of the occasional black gums and sweet magnolias that rise out of it. The only things that moved were a hawk and a turtle. The hawk hovered in slow circles high above our boat; and the turtle slithered noiselessly from the black mud under an overhanging bank into the thick-looking black water that our propeller churned into yellowish foam.

The hounds whimpered and strained at their rope leashes as we passed other gum trees freshly stripped of their berries, but that’s as close as we came to seeing any bears on our way in. After half an hour or so we arrived at the dam whose gates control the flow of water from Lake Drummond through the feeder ditch into the Dismal Swamp Canal. The level of the canal is of more than local importance, since it is a link of the Intracoastal Waterway.

Mr. Cherry, the superintendent at the dam, came down to his dock to meet us. In spite of his recent exploit of shooting a bear from his bedroom window, he has a live-and-let-live attitude toward most members of the bruin tribe.

“I used to go after ‘em when I was younger,” he told me, “and there are plenty of ‘em around here for y’all to hunt, but now I leave ‘em alone unless they pester me out of all patience. These days I do most of my killin’ on snakes. I’d rather kill a rattler or a moccasin than the biggest bear or the finest buck that’s ever been taken out of the swamp.”

While we are on the subject of snakes—we didn’t see a single one. There are plenty of them in the swamp, of course, but by the time the hunting season opens they usually have pretty well quieted down for the winter, and swamp-wise sportsmen refuse to concern themselves over what they say is just about one chance in a million of getting bitten.

We unloaded our boat and packed our duffel a few hundred yards along a muddy trail leading through jungle-thick brush to the comfortable camp of the South Side Gun Club, whose members’ hospitality Lloyd and I were enjoying. Then we went back to the dam and listened to Cherry tell bear and snake stories while we waited for the rest of our party.

Out of the first boat that arrived there stepped a tall, white-haired man who didn’t carry a rifle, but had a couple of good-looking hounds on leash.

“That’s Cortez Temple,” Ed told me. “He has a farm on the edge of the swamp a few miles below the state line in Carolina, and I reckon he knows more about the Dismal than anyone else alive. He’s been huntin’ bear and deer in here all his life. Now his doctor won’t let him go huntin’, but he just couldn’t stay away when we told him we were goin’ to have a bear race. ‘Evenin’, Mr. Temple. How many bears was it that you told me was the most you ever killed in one year?”

“Sixty-two,” Temple said in a matter of-fact way.

Sixty-two seemed to me to be a lot of bears, but before long I was to find out that Cortez Temple was a lot of hunter.

BY THE TIME all the dozen members of our party got to camp it was mid-afternoon, too late to start a drive. So Dave and I set out in a boat on the off chance of jumping a bear.

Paddling quietly, we headed up the feeder ditch and turned the boat into a sluggish waterway which branched off from it. At once we were in the heart of Dismal Swamp. Bald Cypress trees thrust their gnarled trunks out of the water. Thick tangles of red maples, magnolias, and black gums grew out of oozy quagmires. In places where deep peat beds covered the underlying clay and sand, groves of dead trees, their roots charred away by the slow ground fires that sometimes smolder in the peat for years, waited for the big wind which someday will topple them. Now and then we skirted considerable areas of fairly dry land lying a foot or two above the high-water level and covered with thick jungles of second-growth hardwoods, brush, and creepers.

It would be both easy and dangerous to get lost in the swamp, and my advice to the hunter who visits it for the first time is to hire a guide who really knows it—and to stick close to him.

Once we were out of sight of the feeder ditch it wasn’t hard to imagine that we were in a hitherto unexplored wilderness, but Dismal Swamp has been very thoroughly exploited through the two centuries since William Byrd gave it its forbidding and accurately descriptive name. Big fortunes were made out of the cutting of its cedar and cypress, but now almost all the good timber is gone, and the lumber companies which own the land don’t consider it worth while even to guard it against the fires which sometimes burn over hundreds of square miles.

At times in the recent war, smoke from these fires was so thick that it served as a screen for prowling German submarines offshore and often interfered with Army and Navy flight training. As a result, the federal government had to provide a measure of fire protection. Discontinuance of this wartime protection now is giving the swamp and its game back to the fire devils, and interest has been revived and intensified in a proposal that the government buy a quarter million acres in the swamp and create a national forest.

This project is endorsed enthusiastically by the Virginia Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries, which sees in it an opportunity to open the swamp to thousands of hunters now barred by lack of transportation and other facilities and by the exclusive privileges given to local hunting clubs on the western side of the swamp by some of the absentee landowners.

The game is there. Bears are plentiful, and there probably are more native Virginia white-tail deer than there were two centuries ago. Adequate cooperative management by the U.S. Forest Service and the state commission could make much of the higher ground produce sizable annual crops of upland game birds. Waterfowl, however, for some unknown reason, seldom visit the swamp.

In the course of our boat hunt we again saw plenty of bear sign but no bears. “Never mind,” Dave consoled me as he swung the bow around, “I guarantee we’ll get one tomorrow.”

It was late afternoon when we got back to camp. Sitting on the screened porch and watching twilight and then darkness steal over the swamp was a creepy experience. Mist, gray-green against the background of marsh and brush, ghosted up from nowhere and slowly thickened until it blotted out even the trees at the edge of the little clearing. The silence became uncanny, and when an unseen hound howled dismally somewhere in the crowding mist it was like a voice from out of this world. A damp chill penetrated my bones.

Two men sitting near me began talking in low voices about some swamp dweller who had been driven by the silence and loneliness to cut his own throat. When they had squeezed that juicy subject dry they got onto the legends about swamp spirits and spooks which are so well believed that many people who live all their lives in the villages on the edge of the Dismal never set foot in it. Of course, the talkers didn’t think there was anything in the stories, but. …

There’s an effective antidote for those Dismal Swamp blues. After we had poured some of it out of the bottle, we were cheerful enough to eat a big meal, and then start a game of penny ante on which no ghosts intruded.

Daybreak in the swamp was as dreary as twilight had been, but with a couple of dozen impatient hounds yelping outside the cabin and half as many equally eager hunters stamping into their boots and demanding breakfast, it didn’t have a chance to get us down.

As soon as we had finished stoking up for a long day we went into a huddle outside the cabin to decide on a plan of operations against the bears. Starting near the camp there is a partly overgrown trail that twists through the hardwood-and-brush thickets, roughly paralleling the feeder ditch for a mile, then turning north and then back east to form a three-quarter loop around an area of relatively high and dry land.

It was agreed that the hounds would be unleashed at the far end of this trail, so that they would drive any game they put up toward standers who would be stationed along the mile of trail that paralleled the ditch. It also was agreed that no one would shoot at anything but a bear or a deer. Bears were what we were really after, but the season was open on white-tails, and some of the hunters who had unsatisfied appetites for venison weren’t going to pass up an opportunity of bagging a buck.

While we were drawing for our stands, Cortez Temple picked up Lloyd’s rifle, sighted it lovingly, and put it down again without saying anything. Some one, forgetting that the swamp veteran’s doctor has ordered him not to go hunting, asked him which stand he had drawn.

He shook his head, smiled, and said: “I’m just keepin’ the cook company here in camp, son.” Then he sat down on the front steps and started playing with a little hound pup which had been busy winning friends and influencing people ever since our arrival.

The three club members who had volunteered for the tough job of hunting the hounds set off along the trail with the dogs at their heels. After waiting a quarter of an hour, the rest of us followed them. Where the path turned into the brush I looked back. Cortez Temple was still sitting on the steps playing with the hound puppy.

By that time the sun was shining brightly, but in the brush it was as dim as twilight. The narrow trail, hedged in by a tangle so thick that you could see only a few yards into it, was a succession of dips into shallow gullies and rises over slight elevations. In the dips we quashed through sticky black mud. On the rises we had to go carefully over exposed tree roots and foot-tangling creepers.

Lloyd had drawn the stand nearest the cabin-a slight elevation where a good-size tree had been wind-thrown across the trail. By standing on its trunk he could see a scant five yards into the brush and perhaps twice that far along the trail in either direction.

Used to open Western country, he shook his head doubtfully. “If a bear comes through here,” he remarked, “he’ll be so close to me by the time I see him, I’ll have to do some fast shooting. And if I don’t knock him over, I’ll have to do some even faster running—if I can find any place to run to!”

My stand was the next one, fifty yards farther along and as closely brushed in. The other hunters cautioned me that Jim, the third stander, would be close to me, wished me luck, and disappeared up the trail.

Then, although it was the end of October, the mosquitoes came down on me—clouds of them, and every one ravenous. For what seemed a long time nothing else happened. I couldn’t see anything but the green walls that fenced me in, and I didn’t hear anything but an occasional muffled cough from Jim. Finally I called to Lloyd, got a low-voiced reply, and went back along the trail to see what he was doing. He was swatting mosquitoes and cussing fluently. He hadn’t seen or heard any more than I had, and I went back to my stand.

FOR ANOTHER long time nothing at all happened. Then the silence of the swamp was broken by the far-away baying of a hound. Another and another chimed in until it sounded as if they all were running on a hot scent, but after a few minutes the chorus dwindled to uncertain individual barks which soon died away.

But 10 minutes later I heard the hounds again. Now they seemed much nearer-close enough for me to hear someone urging them on with high-pitched yells of “Hunt ‘im! Hunt ‘im ! Hunt ‘im!”

There’s no other music so exciting as that made by hounds and hunters. It set my pulses pounding, and I stared expectantly into the brush until my eyes ached. In the hope of being able to see over the obscuring green screen that I couldn’t see into, I looked around for a tree I could climb. A few yards back in the tangle I spotted just what I needed—a gnarled, weather-bleached stump about eight feet high. After a couple of hurried failures, I scrambled to its top.

There I waited impatiently, but no bear came crashing through the brush across the trail from my perch. The sound of the hounds didn’t come any closer, and after a while they seemed to separate, some working toward the east and some toward the west. Then I heard a rifle shot, followed after a couple of seconds by two others close together. They sounded as if they came from at least half a mile up the trail.

Again for a long time nothing happened, and I took the opportunity for a good look around me. I couldn’t see Lloyd, but in the other direction the cover wasn’t quite so thick, and I could make out Jim. He was perched precariously on the trunk of a big down tree, with a double-barrel shotgun in the crook of his arm.

Then I saw something black and big moving quietly and quickly through the brush behind him. It was a bear! My rifle brought itself up to my shoulder, and I lined the sights on the black body and squeezed the trigger.

Maybe a sapling deflected the bullet, or maybe it was just a lousy shot. Either way, it didn’t do anything to the bear but scare it. The animal spun round so that it was broadside to me, shifted into high gear, and headed straight for the tree trunk on which Jim was sitting. Before I could lever another cartridge into the chamber it was scrambling over the trunk, not six feet from him. Then it bolted across the trail, skidded to a stop, and came tearing back.

By that time Jim, justifiably startled but still balanced precariously on the log, had jerked his gun up. His hurried shot sent a rifled slug smacking into the brush a few inches above the bear’s head, and the gun’s kick unbalanced him and knocked him backward off the tree. The panic-stricken bear kept right on going, hurdled the trunk and just missed Jim, who was sprawled on his back on the ground behind it, and plunged into a thicket before I dared risk another shot.

Attracted by the shooting, Lloyd came running up. A couple of minutes later, while we were still trying to decide what to do next, Dave and two other hunters, with three or four hounds at their heels, arrived breathless from the other direction. The hounds’ neck hairs bristled when their noses caught the bear smell, then they were off on the red-hot trail, running with their heads up and giving tongue in a way that promised a short chase.

Dave slanted an experienced eye in the direction they had gone and shook his head. “We can’t get through there—too thick and boggy,” he decided. “But there’s a cross trail, and if we get on it in a hurry we may be able to cut that bear off. Let’s go!”.

We all pounded down the trail toward the cabin, jumping or scrambling over the trunks of fallen trees, slithering through mud, tripping over roots, and getting our feet snarled up in creepers.

After a couple of minutes we came to where the narrow cross trail branched off, and turned into it. Then we saw that there was someone ahead of us. It was Cortez Temple. He wasn’t running, but he was walking almost as fast as we could run over that bad footing. He was carrying an old single-barrel shotgun that I recognized as one I’d seen standing in a corner of the cabin kitchen. When he heard us and turned his head, we saw that his blue eyes were blazing. He pointed down the trail.

“Bear just crossed, with hounds right after him,” he said. “We’ll get him. Come on!”

“How come you got here so quick?” Dave asked him as we hurried along in his wake.

“I was sitting on the cabin steps and heard the shots and then the hounds,” the veteran explained. “Anyone hit him?”

Jim and I had to admit that we’d wasted our ammunition. Cortez Temple grunted. “Here’s where he crossed,” he said, and led the way into the brush.

It seemed a long time since we had heard the hounds. “That bear’s likely swum the feeder ditch,” someone said. “Once he’s across it, he’s got us licked.”

Dave was just opening his mouth to reply when what sounded like the daddy of all dogfights broke out in a hardwood thicket a few hundred feet ahead of us.

“They’ve bayed him!” Cortez Temple said. “Fan out, boys! Watch out you don’t hit the dogs, but soon as you can get a clear shot at him, let him have it!”

Fanning out in that tangle was easier recommended than performed, but we managed to form a sort of ragged skirmish line and, with rifles and shot guns ready, advanced on the thicket. The sounds of the scrap going on in there had reached a new high of snarls, howls, yelps, and deep-throated growls.

When we got to the edge, a big stump in my way made me drop behind Temple. A few steps more, and we could see into the thicket where the bear was making its last stand. Reared up on its hind legs, it was snarling and cuffing at the worrying hounds.

“Now!” Cortez Temple said softly.

His old single-barrel gun went smoothly to his shoulder and, a split second later, blasted out a slug. At almost the same instant, Lloyd’s and Dave’s rifles spat. The bear spun halfway round, slumped over sideways, and went down with the hounds tearing at it.

When we got into the thicket we found a very quiet bear. Any one of the three shots which had hit it would have settled its account.

Cortez Temple stood looking down at the carcass. After a moment he shook his head sadly.

“What’s the matter, Cort?” someone asked. “Ain’t he big enough to suit you?”

“Nice he-bear, with plenty of good eatin’ on him,” the veteran said. “But I just remembered that I clean forgot I’d promised the doc not to go huntin’ anymore!”

It wasn’t a very big bear-something less than 200 pounds—but getting it out of the brush wasn’t too easy. We tied its legs together, strung it on a sapling, and sweated happily over the job of carrying it to camp.

Lloyd had the heavy end of the load on the final leg of the trip. When we got to the cabin he dropped the pole, swabbed his wet face with a bandanna, and grinned widely. “What I want to know,” he said, “is what darned fool named this swamp Dismal?”

This text has been minimally edited to meet contemporary standards. Read more OL+ stories.