HATCHET’S FIRST HUNT isn’t going as planned.

Every trainer I consulted offered similar advice for our inaugural duck hunt: Set up with a good view for my young Lab. Take just one other hunter, one who won’t miss. Don’t hunt with other dogs. Keep it short—30 minutes, tops. Make sure he has fun. In other words, control everything you can because you can’t control the ducks.

Instead, Hatchet and I are anchoring a line of three shooters plus two guides in a thawing North Dakota cornfield. We’ve already whiffed on a few teal. The setup isn’t bad: We’re hiding in standing corn beside a seep peppered with full body and floating decoys. Hatchet’s been heeling in paw-sucking slop for nearly an hour, trying to keep his footing in the cold mud as he looks for the ducks he can hear but not see above the cornstalks.

So I wrap my own jacket around his wet fur and pull the little Lab into my lap. It’s not like I’m shooting—that’s one rule for our first hunt I haven’t broken, at least. Handling Hatchet is more important than killing a couple ducks for myself.

I know this is a far cry from what most old-school waterfowlers imagine when they talk about the attributes of a great duck dog: hard-charging, tenacious, and uncompromisingly tough. But those traits come with drawbacks, and Hatchet was specifically bred to be free of the flaws that plague so many American retriever bloodlines. That introduces a fresh set of trade-offs. The doubt creeps in as we wait, and I wonder if my Lab will have the grit to make it as duck dog.

Someone down the line starts calling, and we both turn our attention back to the sky.

Coming to America

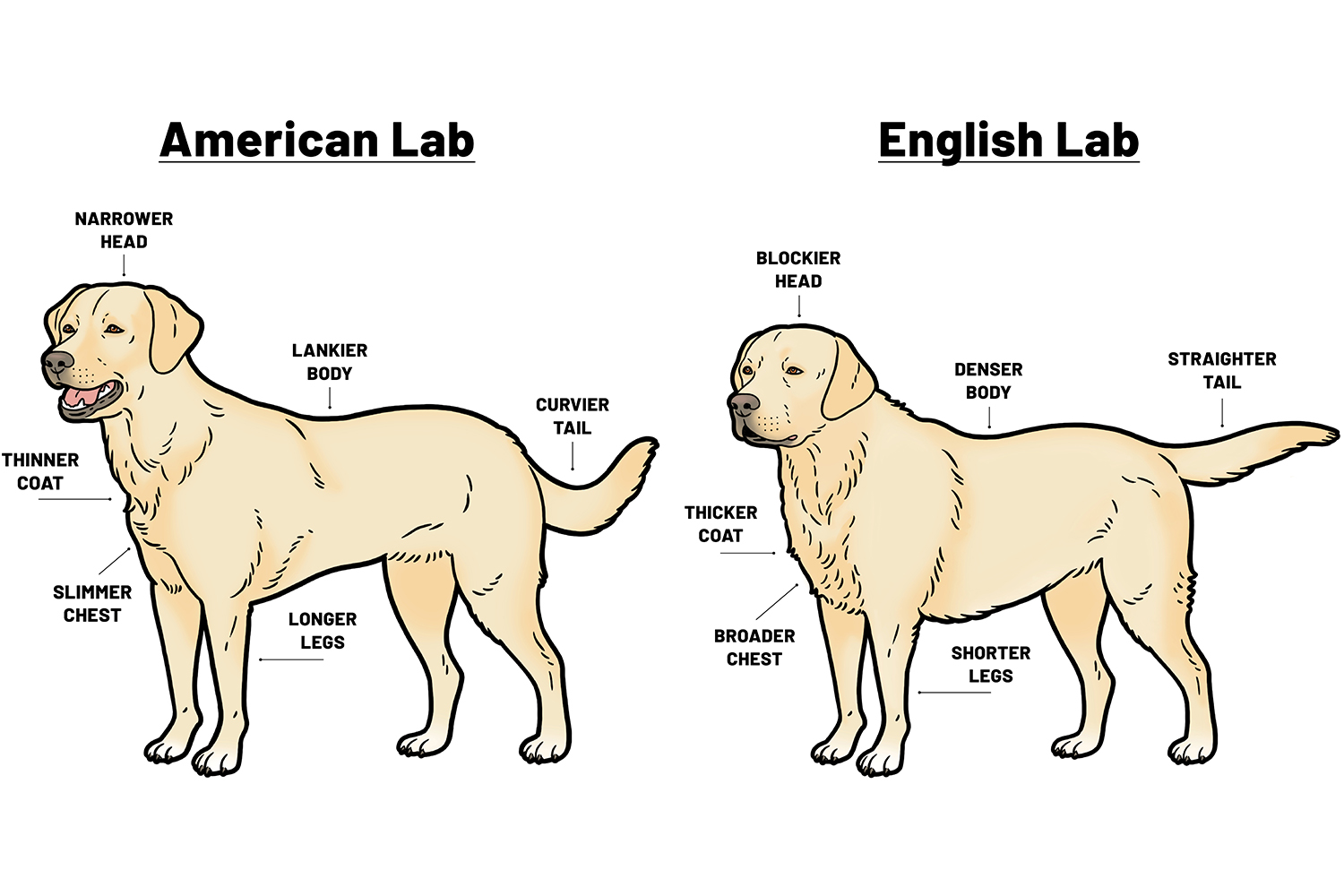

Hatchet isn’t just small because he hasn’t filled out yet. He’s a pure British Labrador who will max out around 68 pounds. (“British” refers to any Lab from the British Isles; Hatchet happens to be Irish.) His appearance seems to confuse strangers. “Does he have some Lab in him?” they’ll ask, eyeing his compact body and straight tail.

British Labs are nothing new in American duck blinds, hunt tests, or field trials. Trainer and breeder Robert Milner popularized U.K. bloodlines in the U.S. when he began importing British Labs to Wildrose Kennels in 1983. More big-name kennels specializing in British sporting lines have emerged in the decades since: Double TT British Kennels (1998), Blue Cypress Kennels (1999), Southern Oak Kennels (2012), and so on.

But even in the last few years, trainers and breeders have noticed a fresh demand for British-bred dogs in the U.S., where the Labrador retriever has reigned supreme as our favorite breed since 1991. This trend is noticeable enough that it has some hunters wondering: Could British Labradors eventually replace American Labs?

The American Kennel Club recognizes a single breed of Labrador retriever, so American and British Labs aren’t distinguished by any major genetic differences. While physical differences can and do exist between the two, size is usually the only reliable indicator of heritage. Instead, behavior and training preferences have shaped Labs so they reflect, somewhat comically, the stereotypes of their owners. American Labradors are vocal, enthusiastic, high-strung. Brits are reserved, quieter, polite.

“The interest in British Labs has been there for years,” says Dave Bavero, owner of Waterstone Labradors in Boerne, Texas. “But I’ve definitely noticed in the last three or four years that people are really starting to realize [their appeal].”

I first spoke to Bavero in 2020 when I called a dozen British kennels within a day’s drive of my Arkansas home. I had decided on a British Lab for the same reasons many hunters do: I wanted a fired-up bird hunter, an easygoing house dog, and a smaller retriever that I could stick in a kayak or carry down the mountain in an emergency. I decided on Bavero’s Labs because he whelps just a few litters a year, leaving him time to answer my questions long after I picked up my pup. Bavero competes in hunt tests, but he’s also a bird hunter and the only breeder who bothered to vet my intentions as a dog owner.

British Labs have always made good hunting dogs, says Bavero, but they’ve often been dismissed by American handlers for field trials and hunt tests. (Useless as trials or tests may seem to hunters like me who just want to kill birds over a good dog, there’s no denying they influence breeding.)

Meanwhile, Brits breed for what Bavero calls “natural game-finding ability,” a trait that’s rewarded more in British hunt trials, where dogs are handled to an area, then encouraged to search for birds as they would while hunting. Handling is still required but it’s less technical. The cultural emphasis on honoring other dogs has also resulted in calm, steady lines.

“The stigma has been that British Labs are not as competitive of dogs, but you’re starting to see more of them” in trials, says Bavero, who began importing Labs from Ireland with his business partner in 2018. “But a lot of that stigma has been how we [Americans] have been training them: If you want to run a hunt test, you have to put a lot of pressure on the dogs. … The American style has been kind of what we do with most things. Build them up and break them down.”

British Labs are known for their soft temperament and can shut down under too much pressure. It’s not an insult to tell a Brit their dog is soft. On the contrary, it’s a desirable trait, and one of the reasons force fetching and e-collar training is almost nonexistent there.

“We just didn’t know about e-collars,” says Matty Lambden, a snipe hunter, field trial judge, and owner of Tamrose Labradors in central Ireland. “So it was never an option for our training. We just had to adapt to the dog’s abilities.”

Bavero has been tapering his e-collar use after visiting Ireland and learning from Lambden, who exports finished Labs and frozen stud semen to Bavero in the U.S. Lambden says he trained three field trial champions before he ever heard of e-collars or force fetching. He acknowledges some brilliant trainers may use them, but he’s managed well without. They’re not tools he’s interested in. Most American hunters (myself included) won’t train or hunt without an e-collar.

Lambden is clear about what he likes in a Labrador. The stereotypical block-headed English Lab with stumpy legs isn’t his cup of tea. He favors “stylish, good-looking dogs,” which means a tall dog with proportional legs, a low tail, and good eye contact. These are known as field Labs, and they look similar to American Labs. A quiet dog is nonnegotiable.

“I have 15 dogs,” says Lambden. “I could walk around me kennels and there won’t be one—not even one squeak. It’s a fault over here. If your dog makes a”—here Lambden imitates an excited whimper—“in line, he’s gone. You drove three hours and the dog gives a bit of a cry, he’s out the door and you’re knocked out of the competition. So that’s why we don’t proceed with that [trait] or breed off those dogs. You’re better off putting it all into a dog that you know is going to be quiet.”

If I hadn’t heard the same report from Bavero, I might suspect Lambden of exaggerating. And Hatchet is proof enough. Weeks passed before I heard his first bark, and whines have always been reserved for bathroom emergencies. Today he barks or growls only if he suspects an intruder.

Most telling of all, perhaps, is the fact that British Labrador exports are a one-way migration. When I ask Lambden if he knows of anyone in Ireland, England, Scotland, or Wales who imports American-bred Labs, he thinks hard.

“No, there’s none,” he says at last. “I’ve never heard of anyone, ever.”

Slow and Steady

As the shooting continues without a retrieve, Hatchet’s excitement ebbs. I’ve just decided to fish a dummy out of my blind bag when a flock of greenwings swoop into the decoys.

“Mark,” I whisper into his ear, which is still just inches from my face. When Hatchet sees the teal, his muscles tense and his paws dig into my waders. A few shots ring out and a drake drops stone-dead into the decoys. This time, I don’t whisper.

“Hatchet!”

He launches off my lap, hard enough to topple the chair if it weren’t sunk in the mud. Instead, I get a perfect view of my dog beelining for his first duck. He sniffs the teal once, twice, then gathers it gently into his mouth and trots back. I meet him at the water’s edge, but I don’t take the bird. I just let him hold it a minute, still not troubling to keep my voice down as I tell him what a good boy he is.

When a crippled hen splashes down next, Hatchet tears across the shallow water and pounces. She slips away, and he chases her around the pothole, getting the warmup he needs as everyone cheers from the bank. It makes his next retrieve, on a fat greenhead, seem almost routine.

Most of the time Hatchet can’t mark well from the standing corn, so I often walk him toward the ducks and he carries them back at heel. Come midmorning, he’s retrieved a dozen, and we’re both caked in mud. He sleeps the whole way home, more brown than yellow.

The next morning finds us in another cut cornfield. Today, we’re hunting geese with the outfitter’s dog, a big black Lab who’s there to work, not wait for us or any release command. Still, I want to get Hatchet on birds. I tell him to kennel up, but each time Hatchet tries to enter the brushed-in dog blind, his vest catches and he’s rebuffed. His ears droop anxiously and, thinking the hang-up is a correction, he won’t kennel at all now. It’s getting light and I’m considering cramming him into my layout when I notice Hatchet is barely bigger than the decoy beside him. He’s never even seen a goose yet. A pissed-off honker could thrash him once and ruin him on geese forever.

This time, I follow the rules. I put Hatchet up in my truck.

It’s just as well. We shoot one lesser and a snow for all our trouble, and the outfitter’s dog would’ve beaten Hatchet to both. When I let him out of the truck, he’s unsure even of the dead geese. Two young guides hype him up, tossing and dangling the big birds until he gets excited enough to retrieve one. I’ve been watching from the sideline, but he brings it right to me.

The Case for American Labs

In many ways, a bird dog is only as good as his trainer, and in the months leading up to Hatchet’s hunt, we’ve both been trained by the best. Tom Dokken is the legend behind Dokken’s Oak Ridge Kennels and the inventor of the Dead Fowl Trainer. The Minnesota native has worked with thousands of dogs over his four-decade career and trained both American and British Labs. He doesn’t play favorites, and if you ask him what kind of dog he prefers, his answer is always the same: “One that wants to work.”

“I always tell people to get the best bloodlines you can buy,” says Dokken. “I don’t care if it’s British, American, whatever it is. You can have dogs—again, whether it’s British or American—that have some talent. And then you can have dogs that have a lot of talent.”

Still, Dokken is distinctly American in his approach to any retriever. That’s for a few reasons. British-style trainers like Lambden may take two to three years to finish a gun dog, spending the first year of a pup’s life focusing on obedience and steadiness. Dokken, meanwhile, operates on a professional trainer’s timeline. Oak Ridge Kennels offers two-week bird and gun introductory courses for pups as young as five months, with more advanced training programs available after that. Responsible e-collar work and force fetching help dogs understand what trainers are asking for sooner. Most clients can’t afford to put their dog through several years of training. And even if they could, most hunters aren’t willing to wait a few years to take their Lab hunting. I certainly wasn’t. I spent my 20s living in a cramped apartment and dreaming about a bird dog. Now that I can responsibly own one, I want to hunt him ASAP.

Read Next: Tom Dokken Is the Godfather of Retriever Training in America

“There’s field trial training, where they set standards,” Dokken told me in the weeks leading up to Hatchet’s first season. “When you hunt, you set your own standards. There’s no wrong answer. That’s just what you want.”

During Hatchet’s puppyhood, I had unwittingly honored the British tradition of steadiness. I understood and applied the golden rule of obedience training: Never give a dog a command you can’t or won’t reinforce. But I had no idea how to train a gun dog. That’s where Dokken came in.

From there, Dokken introduced both of us to the e-collar as a training tool that reinforces existing commands, not a means of punishment. (Say what you will about e-collars, but Dokken’s practice of training his dogs to recall on its tone function, rather than blowing a shrill whistle over a field of wary pheasants, is nothing short of brilliant.) Dokken also taught me how to force fetch, a process Hatchet took to easily and eagerly, in part because we paid attention to his personality. As Dokken diplomatically puts it, Hatchet is “not tough.” Because British Labs are typically soft, they can pose challenges for amateur trainers like me.

“Get a dog that has enough talent that they’re going to make up for your mistakes,” Dokken advises. “Because if you get a dog that’s super soft and you’re making mistakes at the wrong time, you might just shut that dog totally down. Whereas a professional trainer, if he has enough experience, he’s evaluating that dog early on to know where that dog’s limits are and where the correction levels are in order to keep it working.”

Hatchet and I trained at Dokken’s farm in South Dakota, a wind-swept prairie with big water and thick cover. It’s a fair microcosm of American bird hunting. Retrievers in the U.S. are often asked to navigate ocean surf for sea ducks, swift rivers for mallards, and half-frozen potholes for pintails. Our hunters work their dogs in prickly deserts, steep mountains, and dense woods for quail, chukar, and grouse. Hunting here is more dangerous than in tidy British farm ponds and neat hedgerows.

All of this raises a bigger question. If we import British Labs, breed them in the U.S., train them in the American way, and hunt them across America, at what point do they become, well, American Labs?

Even as British Labs become more popular, the trainers I spoke with see their lines and training traditions continuing. In his decades of hunting and training, Dokken has personally owned five Labs; all of them have been American. For his part, Bavero says he’ll continue to import dogs from Ireland to produce what I think of as first-generation pups, like Hatchet. As Lambden puts it, he doesn’t think it’s worth “opening the can of worms” between American and British breeding and training styles.

“We’re lucky to have these animals around us,” says Lambden. “They bring such pleasure to our lives, and we’re so passionate about it—it’s terrible. We don’t think training should be done this way [with e-collars], and [Americans] don’t think our dogs can be trained to their levels. It’s gonna go on until the end of time. The dogs are all getting well trained, and what they’re capable of doing is fantastic. That’s all we want really in life. Enjoy your life and enjoy your dogs.”

Wild and Free

On our drive home from North Dakota, Hatchet and I stop at the Dokkens’ for what feels like a final exam. Tina Dokken and I take our Labs out each afternoon for pheasants. The first day, Hatchet trails Tina’s veteran chocolate, Sassy, most of the time. Hatchet follows Sassy the next day, but he’s starting to hunt for himself too. By the third afternoon, he’s too interested in birds to notice another dog.

Finally, the day before we head home, Tom waves his hand toward the fields that stretch around their home.

“Why don’t you hunt just the two of you today,” he says. “Just let Hatchet do his thing and follow him around. Don’t rein him in. Have some fun.”

Hatchet and I scramble out the door. It isn’t until I’m loading my shotgun that I realize I’ve never bird hunted by myself. I’ve always tagged along with buddies and their dogs. Then I look at Hatchet, wriggling with excitement on the tailgate, and correct myself. This is no solo hunt.

“Hunt ’em up!” I tell him, and he leaps into the rustling grass.

Obedience is essential to living sanely and safely with any dog, but especially a gun dog. Hatchet can stay on place for hours and heel off leash when I cross a busy road. Better, though, is releasing him from heel and watching him race away.

Breaking rules will become a hallmark of our relationship. He curls up in the passenger seat of my truck, ranges ahead of the quad while I’m checking trail cams, steals my pillow at night. It’s clear that my mild-mannered British Lab is happiest when he’s running wild. And truthfully, I can’t think of much else that makes me happier. What’s the point of having a bird dog if you don’t cut him loose?

In our first season together, we will hunt roosters in Nebraska, chukar in Utah, and redheads on the Texas coast. It will feel like we’re both making up for lost time, cramming in as much variety as we can, wherever we can.

For now, though, this afternoon hunt is all we care about. Within 10 minutes, Hatchet puts up a field-edge rooster and I dump it into a clover plot. Hatchet is on it in an instant, then trots over with a mouthful of pheasant. We’re both panting and grinning, and he lets me tousle his ears before he darts away again, nose to the ground and tail whipping like mad over the golden prairie. I tuck the rooster into my vest and jog after him. He may be a British Lab, but I’ll make an American out of him yet.

This story originally ran in the Migrations Issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.