Dan Wolfe held Red’s head steady as I pulled the cinch up tight around the horse’s middle, stuck my toe in the stirrup, and swung myself up into the saddle. Dan looked up at my freshly shaven face and smiled.

“Hey, pardner, you look so good the deer won’t know who you are or what you’re up to,” he said.

“That’s the idea,” I answered. “I figured a bath and shave just might change my luck some. What’s on the menu for supper?”

“Cowboy beans and steak, what else?” said Wolfe. “That is, unless you just happen to come leadin’ ol’ Red back with one of those big bucks tied across the saddle and want some fresh liver and onions.”

“And miss your steak and beans? Not a chance.”

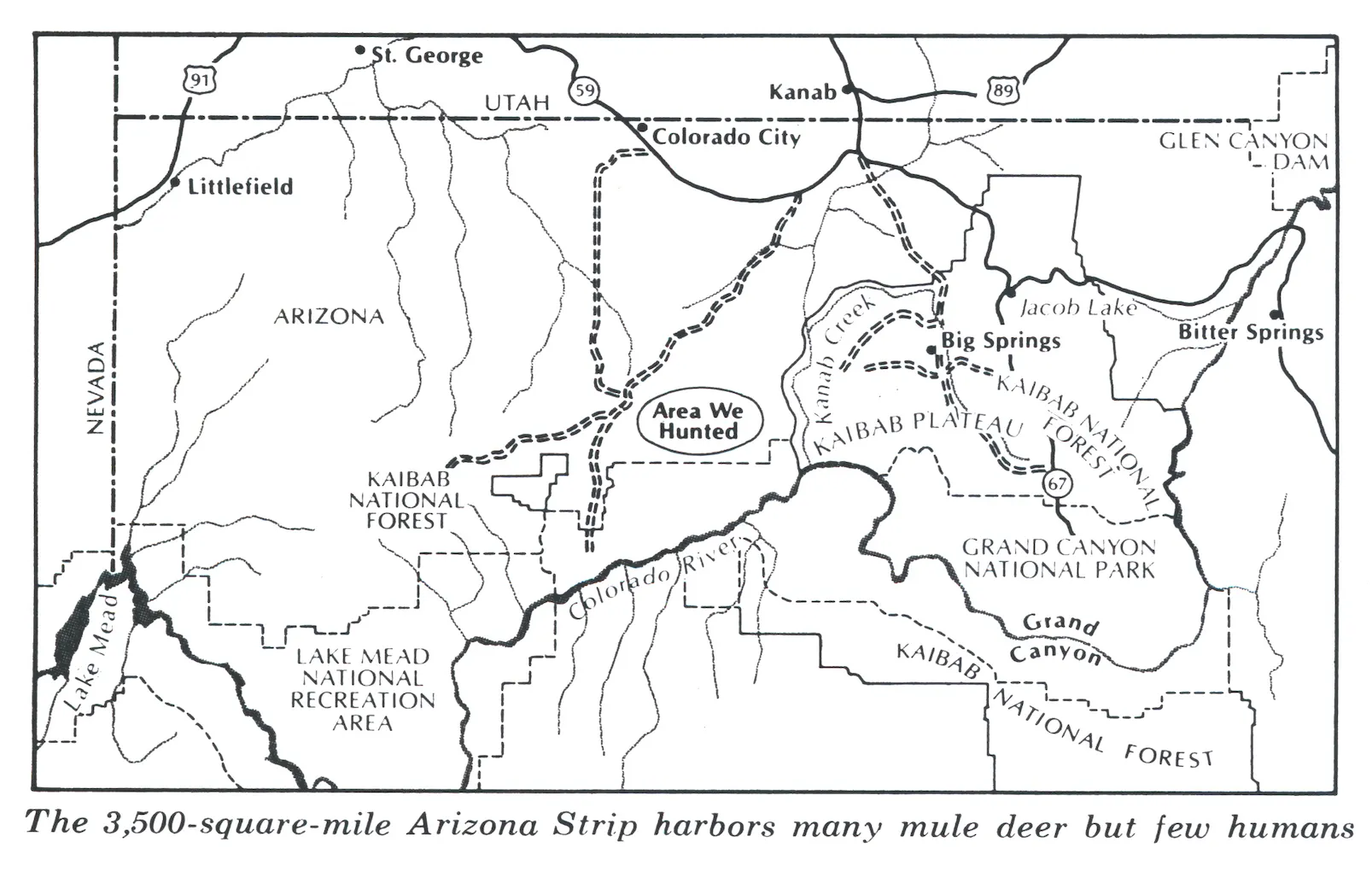

With that I turned my mount’s head south, toward the Grand Canyon. I’ve hunted in some of the most wildly beautiful and forlorn terrain this planet has to offer from glaciered peaks to scorching deserts. But for spectacular scenery and eerie endlessness, nothing is quite like the land in which I was now hunting mule deer-the fabled Arizona Strip. The almost completely uninhabited rectangle of territory is bounded on the south and east by the great gorge of the Colorado River and on the north and west by Utah and Nevada.

This land is noted for the unbelievable antler growth of its mule deer but also was the scene of one of history’s most tragic examples of the evils of trying to overprotect a deer herd — the great Kaibab debacle of the 1920’s. In 1920 as many as 100,000 deer lived on the Kaibab plateau, but this inflated population, created by a no-hunting regulation and strict predator controls, brought on an era of starvation and range destruction that wiped out nine of every 10 deer within the next two decades. A tragic lesson, and one that’s often ignored by wildlife “preservationists.”

Today, thanks to sound management practices that rely on a yearly deer harvest by sport hunters, the Kaibab is once again producing trophy bucks. West of the Kaibab plateau, where we were hunting, there has always been a healthy deer population with big bucks that display awesome antler growth.

The antler growth of that race of deer is so unusual that the rack on a one-year-old buck may have as many as four points on a side. Of course, feed conditions for any given year have a lot to do with antler growth, but after a Strip buck is four years old or so his antlers arc likely to be of the nontypical type with literally a dozen or more points growing and twisting in all directions and in all sorts of weird shapes.

Arizona deer hunting is by drawn permit only, but the area in which we were hunting, known as Management Unit 13, is so big that some 2,500 permits were allowed there in 1974. Even with that many permits there’s little likelihood of seeing other hunters because the area includes something like 3,500 square miles.

Generally, Arizona’s deer season is two weeks long and begins around November 1. You can get information about guides and a booklet describing the current season in each part of the state and procedures for applying for a hunt. Write: the Arizona Game and Fish Department, 2222 W. Greenway Road, Phoenix AZ 85023.

I was hunting with outfitter and guide Hunter Wells, who operates out of Prescott. Hunter operates a year-round guide service for mountain- lion hunters as well as offering hunts for Arizona elk, pronghorn, desert sheep, and deer. His clients have taken such fine trophies out of the Strip country that I signed on for the 1974 late-fall hunt.

Hunter’s father Fred, and two brothers, Rube and Fred Jr., helped out with the guiding and camp chores, and there was head cook and wrangler Dan Wolfe and rancher Eddie Balmes, who helped with the wrangling. The hunters, in addition to myself, were Carlo Von Moffei, who came from Canada, and Californians Dan and Donnie Smith.

The gently rolling juniper-dotted knolls seemed to go on forever. Deer don’t have to hide here, I thought. They just get so lost no one can find them.

Because of the short hunting season, most Arizona guides can take out only one party per season, and must charge quite a bit in order to stay in business. Many of the out-of-staters Ready to scout a rim, I grab my rifle who hunt in northern Arizona are guided by ranchers, landowners, or cowhands who agree to guide a hunting party while they do their own hunting. It’s a cooperative system, of sorts. For example, if Hunter Wells is already booked up, he might refer a prospective client to one of the part-time operators.

Days are dry and warm, but nights are chilly in the Strip country, and I’d selected my clothing so I could use the layer system-shirts, vests. and jackets that can be stripped off as the day warms up. The hunter also needs a sleeping bag and personal kit, rifle, and ammunition. The guides usually take care of everything else.

You can hunt the Strip country without a guide, but it’s easy to become hopelessly lost in this remote area. Also, the horses offered by guides such as Wells greatly enhance your chances of bagging a trophy buck. A hunter on foot can’t see over and around the scrubby pines and junipers nearly as well as he could on horseback.

When the Strip-country deer season opened, I was hunting whitetails in Maine’s north woods; by the time I arrived in Arizona the hunt was well under way. I met Eddie Balmes in Prescott, and we flew by private plane to the little town of Kanab, Utah, just over the Arizona-Utah border. I selected Kanab as a meeting place because my schedule was tight, but hunters and Arizona guides ordinarily meet in a more convenient central area such as Prescott, Phoenix, Kingman, or Flagstaff.

We were met in Kanab by Rube Wells, and after we picked up some grub plus a few extra bales of hay for the horses, we headed into the Strip country.

I’d waited a long time for a crack at the big Strip-country deer and had no intention of muffing a shot because of a bum zero, so we stopped during the ride to camp, and I checked out the rifle. The zero was dead-on.

My rifle was a Nelson-stocked Model 70 Winchester barreled in .280 Remington and topped with Leupold’s new 2.5X-to-8X scope. I’d used this rifle in Africa, Asia, and Canada but never in the U.S. I expected to get medium-to-long-range shots in the Strip country, and I’d need an accurate, flat-shooting rifle. Under these conditions a good bolt-action .280 is about ideal. I was shooting 55 grains of No. 4350 powder behind a 140- grain Nosier bullet.

By the time we got to camp late in the afternoon, Dan Smith had already bagged a big five-pointer (Western count-five on a side) and the party had passed over several bucks that would be “takers” almost anywhere else. In hunting country where the next hill or dry wash might produce a record-book trophy, you tend to think twice before filling your license with even a good four-pointer.

Camp had been pitched on the side of a gentle slope near a protective stand of junipers. There was water for the horses in a shallow basin Jess than a mile away. At the crest of the hill was a ring of large stones that had been put there hundreds of years before. The circle was about 15 feet across and had once been the foundation of a prehistoric Indian dwelling. The floor of the one-room affair had been dug down several inches as added protection against the bitter Arizona high-country winter and also for coolness during the parching summer months. The entrance had faced south to let in maximum light. The ancient campsite was probably a treasure trove of Indian artifacts, but we did not disturb it, other than to examine a few bits of pottery scattered on the surface.

That evening — as the Arizona sky splashed over with gold, lavender, and scarlet — Hunter filled me in on the hunting situation. There was more water than usual for that time of year, and so the deer were not traveling very often or very far. Finding a really good buck would be a matter of ferreting him out of one of the rock ledges or canyonside overhangs where wise old bucks prefer to hide out. The plan of operation for the next day was to ride the rims of the tributary canyons leading to the Grand Canyon and glass the ledges for bucks.

“Hey, Dan,” Hunter yelled as soon as we’d gone over the next day’s game plan, “how about digging up some grub?”

“Keep your shirt on,” Dan yelled back from the cook tent. “I’ve got to keep stirring these beans so they won’t eat through the pot. I’ll bring the shovel when I get good and ready.”

“Sounds just like an old-time trail cook,” I said. “But does he really need a shovel?”

“Just like I said,” replied Hunter. “We’ve literally got to dig up our supper. It’s buried just about where your feet are.” Before I could answer, Dan appeared with a long-handled shovel and started digging right in front of me. In a few seconds I caught the flash of aluminum foil, and a moment later Dan lifted a large foil-wrapped chunk of something from its burial place. The foil shield was peeled back, and Hunter sliced a juicy piece of white meat from a turkey.

“Before we leave camp in the morning,” Dan explained, “we dig a hole like this and line it with hot coals from the campfire. We put in that evening’s meat, cover it with more coals and a layer of earth, and let it cook all day.”

That night, as the November moon rose over the knoll above our camp and outlined the cold circle of Indian rocks, I wondered what kind of man had lived there, what long-gone tribe he had represented, and if he had sat by this campfire and dreamed of great bucks with high-reaching antlers.

The next morning we stuffed ourselves on eggs, bacon, and hotcakes, then saddled up and headed east toward one of the major canyons that lead into the Grand Canyon. In darkness the world is only as wide and as far as a man can see. But with the coming of dawn the tremendous sweep of the Arizona Strip opened up before us farther than the eye could reach.

The gently rolling juniper-dotted knolls seemed to go on forever. Deer don’t have to hide here, I thought. They just get so lost no one can find them.

As everyone who has visited the Grand Canyon knows, nothing about the surrounding countryside indicates that nearby the earth is split by a gigantic rent in the earth’s crust. It was the same with the lesser canyons in the area we were hunting. You are riding along what seems to be an unending plain of gentle swells and valleys when your horse suddenly steps through a dense fringe of scrub cedars and you find yourself on the brink of a sheer chasm. A stone kicked loose by your mount seems to fall for minutes, and you can’t even hear it hit bottom.

All day we worked the edges of the canyons, stopping often to glass the rocky rims, but pausing just as frequently to take in the view. Here and there the canyon floors were specked by the sun-blackened remains of a prospector’s hut, and holes bored into solid rock showed where miners had labored a century before.

The closest thing to a deer that I saw the first day out was the two hind legs of a buck or doe as it disappeared into shoulder-high brush. We circled the area and worked our way in carefully but didn’t see the animal again.

As we skirted one wide but fairly shallow canyon, I noticed some deer tracks going in opposite directions. It appeared that the spot had fairly heavy traffic, although the well-used trail did not seem to lead to any water or particularly good grazing area. I couldn’t help wondering where all the deer were that had made those tracks. The trail led generally south. That evening Dan “dug up” some giant T-bone steaks that must have smelled mighty good to the local coyote population. They howled a few mournful tunes as we ate, and the bones we tossed out were gone the next morning.

Was the deer good enough to shoot? I had only an instant to decide. Already I was tracking the deer with my rifle, and through the scope I could see the tips of his antlers: wide and high, gleaming in the late-afternoon sun.

The next day we rode west and skirted some limestone bluffs where Hunter had spotted some good bucks during his preseason scouting. As the day wore on, it became to my notion too warm and still for much deer movement, so I crawled into the sack for a couple hours of shuteye.

About four p.m., after a nap, splash-bath, and shave, I headed south out of camp, hunting alone. The heavy concentration of tracks we’d seen the day before had given me an idea: the deer that had made all those tracks had to come from somewhere, and if a fellow got there at the right time, he should get some action. After riding south for about a half-hour I took another bearing and turned east. This would lead me across the heavily traveled deer trail and — if I had calculated correctly — just in time for the late-afternoon deer traffic.

Horses are usually good spotters, snorting and twisting their ears forward when they see game, but old Red really let me down completely this time.

I don’t think he ever saw the herd of does that broke from cover and trotted up the gentle slope to our left. I counted eight in the first group. Just as I was dismounting, five or six more broke from another patch of junipers and trotted after the others. I tied the reins to a scrub bush, fed a cartridge into the chamber of my rifle, and followed the deer on foot. I hadn’t seen anything with antlers, but it was the height of the rutting season, and I couldn’t imagine that so many ladies would be in one place without a suitor close by.

The deer had disappeared over the crest of the hill. They hadn’t been alarmed, and I guessed they would stop on the other side. All I could do for the moment was get to the top of the hill, keep an eye on them, and see if a buck showed up.

A row of trees along the hilltop made a perfect screen, and a gnarled tree trunk offered a fine rifle rest. The does were about 200 yards away and slightly below me, taking their ease in a shallow draw. It would be a cinch shot if a good buck stepped out in the clearing. Old bucks, though, can be clever, and I knew that if one was there he’d take his time coming out.

After a few minutes the does started walking up the draw and one by one topped a granite rim and disappeared. I was sure that a buck was close by. The safety was off, and I had a solid rest. At 200 yards across open ground a slow-moving deer isn’t a tough target, but I figured he’d probably stop a time or two and that then I’d have a dead shot.

The last doe disappeared over the rim, and there was still no buck. It looked as though I’d made a wrong guess. I stood up and thumbed the safety to the “on” position. Just then a big deer broke from cover at the lower end of the draw and went racing toward the rim where the does had disappeared.

There was a buck after all! But I was caught completely off balance. Was the deer good enough to shoot? I had only an instant to decide. Already I was tracking the deer with my rifle, and through the scope I could see the tips of his antlers: wide and high, gleaming in the late-afternoon sun.

The crosshairs pitched ahead of his chest, and I pressed the trigger. It looked like a good shot, but he didn’t seem hurt. Just as he toppled over the rim I threw another shot at him, but that one I called too high. Missed!

I followed at a dead run for there wasn’t much daylight left and there was a fair chance the buck was hit. My No. l rule for tracking game is to follow up on every animal at which I shoot. No matter how wild the shot may seem or how untouched the animal appears, I make every effort to see whether the bullet has found the mark.

This time it paid off. Just over the rim the buck had collapsed in low cedar brush-completely lifeless. The bullet had hit him squarely in the chest cavity and pulverized both lungs.

By the time I took a few photos and field-dressed the buck, there was very little light left and no chance of getting him back to camp before morning. But if I left the carcass out the coyotes would surely get at it during the night. So I piled limbs and brush over the carcass and placed the deer’s heart, liver, and other morsels on top of the pile. The idea was to give the coyotes enough to eat to keep them away from the deer, leaving an untouched carcass for us to pack out to a processing-and-freezing plant. Next morning when Eddie and I returned, the buck hadn’t been touched, though the heart and liver were gone. It was a good trade.

This story, “Canyonland Trophy Hunt,” appeared in the September 1975 issue of Outdoor Life.