This story, “Christmas Adventure,” appeared in the December 1965 issue.

The beagles had been ranging in the swamp for less than 10 minutes when Mutt bawled loud and clear on a red-hot track. A moment later Jeff joined in and finally Homer opened up. After that, we had as lively and as noisy a rabbit chase under way as any I can remember.

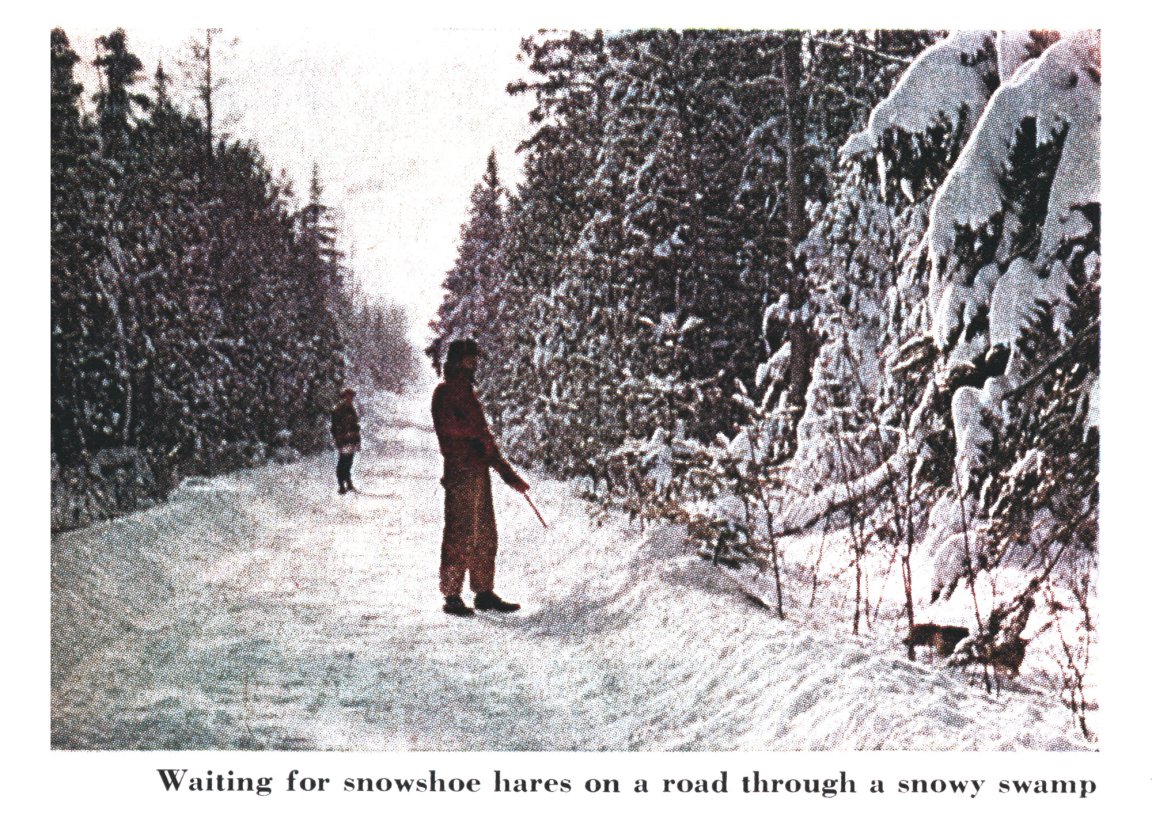

The place was a balsam bog loaded with snowshoe hares in Schoolcraft County on Michigan’s upper peninsula. Frank Sayers, Tom Reynolds, Vic Silk, my sons Park and Bob, and I were deployed at intervals along an old logging road which bisected the bog. Although the mercury hovered at only 5°, all of us became so absorbed in the rabbit chase that no one noticed numb toes and cold ears. Each of us hoped the rabbit would come his way and give him a shot.

“When the dogs strike a track,” Vic had warned, “it often makes all the other rabbits move, so stay alert.”

I strained to see movement in the swamp. The snow was more than a foot deep, and I knew a snowshoe could slip past without being seen. I thought I spotted something, maybe the dark eye of a bunny, but that was all. Then the chase suddenly turned my way with the three beagles in full cry. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw my boy Bob raise his 20 gauge double and then hesitate. An instant later, a rabbit squirted past right in front of me; I didn’t even have time to flip off the safety. Then I heard Bob shoot, and soon I saw him holding up a big, white hare and heard him shouting at the top of his lungs.

“What a Christmas present, what a present!” he kept saying. Not only was it the first snowshoe he’d ever bagged, it was the first he’d ever seen.

All afternoon, the dogs kept rabbits circulating in the swamp, and we did plenty ourselves trying to get shots at them.

It was the second day after Christmas, and we were 650 miles away from our homes, enjoying a relaxed winter holiday. The trip had really started on a November evening after a showing of family summer-vacation movies. Present were Frank and Isabelle Sayers with their daughters Jane, 20, and Ann, 16; Tom and Nancy Reynolds; my wife Doris and myself, and our two sons Park, 19, and Bob, 15. We all live in Upper Arlington, a suburb of Columbus, Ohio. Frank is a real-estate developer and the Reynolds are a husband-and-wife team of dentists. Jane Sayers and my son Park are college students. Ann and Bob attend high school in Upper Arlington.

Someone suggested that it would be fun to take a Christmas vacation. Someone else seconded the motion, pointing out that Christmas is usually damp and dreary in Ohio. Why not go north and enjoy a white Christmas? We also noted that Christmas nowadays often becomes a social whirl that leaves everyone exhausted. That’s when Frank got a million-dollar idea.

“Why don’t we just pack bag and baggage and spend Christmas in the wilderness?” he said. “We could go to our place in Michigan.”

Perhaps Frank wasn’t ready for the response he received.

“I’ll start packing tonight,” Bob said.

“We accept,” Tom added, “before you change your mind.”

“Then it’s a white Christmas in Michigan,” someone else concluded.

It was settled as quickly as that.

To appreciate this enthusiasm, I must describe the Sayers’s place. It’s a snug, attractive, old log cabin beside a gemlike lake deep in the Hiawatha National Forest. No one lives nearby in winter. It is big enough to house a fairly large group and has most of the modern conveniences — up-to-date plumbing, electricity, and running water. But the cabin was built for summer use. It isn’t insulated and, except for a stone fireplace and a pot-bellied stove, it has no heating facilities. The nearest road that’s kept open during the severe Michigan winters is about a mile away. Outdoor Life readers may recall that I described the Sayers’s place in “Three-Year Hunt,” in the June 1956 issue, a story about the first deer I killed with bow and arrow.

Preparing for the trip completely altered the routines of all three families for nearly a month. Even our four-year-old beagle, Homer, seemed to know something special was afoot. Instead of frantically buying Christmas gifts, we held a secret drawing in which each of us drew the name of only one person for whom to buy a present. Of course, all the gifts were for use outdoors — fur-lined mittens, skis, insulated underwear, woolen sweaters.

There was also plenty of activity in our home workshops. We bought a used dog sled and a toboggan, both in bad shape, and repaired them. Frank built a carrier for use on top of his station wagon and bought a pair of old military snowshoes. Using the snowshoes as a model, Frank, Park, and Bob built three more pairs. At first, they found it was no simple matter to soak and steam the hickory slats before bending them into the proper shape, and it wasn’t easy to string the shoes properly with cowhide thongs. By trial and error, however, they figured it out, and the copies were better than the originals.

It was a little easier to assemble ice-fishing gear because we do some ice fishing at home in Ohio. We also assembled a set of emergency equipment- snow shovels, tire chains, a chain saw, axes, tow ropes and pulleys, lanterns, flares, tools and parts for our cars, cans of gasoline and oil.

Long before daybreak on the morning of the day before Christmas, our three-car caravan finally headed north out of Ohio.

Not too long ago, this trip to the Sayers·s cabin would have required almost two days, but now the limited-access highways through Michigan and the bridge across the Straits of Mackinac have reduced it to one day of pleasant driving. We arrived in Manistique late in the afternoon, and although we were only 30 miles from our destination, we checked into a motel. Fresh snow on the upper peninsula had nearly paralyzed traffic, and Frank figured stopping was best.

“Tomorrow, we can get an early start,” Frank said. “It may take all day to open the road to camp and to heat up the cabin. “

At dusk on Christmas eve, all traffic and activity drained from downtown Manistique, and the colored lights in the windows of the homes were the only indication that anybody lived in the small town. Tom and I mixed a bowl of punch in the motel and then we had dinner in the only restaurant which was open. We were the last customers, and when we left, the place was locked up.

The morning of Christmas Day, the male members of the party and Ann Sayers drove northward out of Manistique to Steuben and then turned west toward the cabin. During the night, snowplows had partly cleared the roads, and snow was banked four or five feet high on each shoulder. When we reached the entrance road to Frank’s cabin, we found it completely blocked.

“We’ll have to hike in on snowshoes and try to start the tractor to open this road,” Frank said. The tractor was a vintage model used in summer for grading, hauling firewood, and other such chores.

We hiked a mile to camp on snowshoes through a mature birch and maple forest. The snow was so soft and deep that Homer had to tunnel his way behind us. Except for the tracks of rabbit, squirrel, and a fox, the blanket of white was pure and satin-smooth. In a grove of Norway spruce not far from the cabin, a ruffed grouse exploded from a branch directly overhead and gave everyone a start. Next thing, we were removing snowshoes, tromping snow from our boots, and opening the cabin. Somehow, I had the fleeting feeling that I was arriving home.

While Ann and Bob built fires inside, and Ann started a pot of soup bubbling, Park tackled the immense job of shoveling snow from around the cabin. Frank, Tom, and I fueled the tractor and started it after considerable cranking. Many years had passed since I last cranked a tractor.

Next, we spiked three large logs together into a triangular plow. Three or four passes over the road, with several of us standing on the plow to add weight, opened a path over which the cars could pass with chains on the tires. We had to remove one fallen tree with the chain saw. Then the girls joined us and got the cabin ready for a week of living while the men concentrated on cutting and splitting firewood and stacking it in a shed beside the kitchen. It isn’t often that I feel as pleasantly tired as I did while we exchanged gifts that evening. It had been a hard day, but it was also a Merry Christmas — a really Merry Christmas.

So many things happened the following week that it’s difficult to confine them to one story. One morning, Vic Silk, the National Forest fire warden and part-time guide who was our nearest neighbor — 11 miles away — dropped by and suggested we join him in a snowshoe-rabbit hunt. He had immediate acceptance. “It’s a good year for the bunnies,” Vic told us, “and even though the snow is too deep for the best hunting, we should be able to find some.”

It wasn’t easy hunting, but we had plenty of thrills kicking about in a swamp along the Big Indian River. Snowshoe hunting was a new experience for all of us. We learned that the hares are far more elusive than cottontails. Snowshoes run farther and are much harder to see against the snow. But Homer had the toughest time of all. He’s very short-legged and couldn’t keep up too well with Mutt and Jeff, Vic’s pair of tall beagles. It was amazing to me the way those hounds could keep a rabbit hustling through that heavy, snow-clogged swamp.

Somebody was ice fishing almost all the time because Blazed Trail Lake was less than 100 feet from the cabin. That made it possible to snowshoe out onto the ice, fish for a while, and then return to the fireside for a cup of hot chocolate. For a few days, however, the ice fishing was disappointing. The lake is full of bluegills and perch, and we figured we’d catch plenty. Both fish are willing strikers in the winter, but somehow we couldn’t seem to locate the fish until late one afternoon when Park and Frank began to hit the perch about 400 yards from camp. Just for the novelty, they fried the fresh fillets right where they caught them.

It was cold all through the week and snow fell now and then. The temperature never rose above freezing, and several nights it fell to around zero or slightly below. But we were never uncomfortable. We wore warm clothing outdoors and slept in good Dacron sleeping bags on polyurethane-foam mattresses.

We used a tremendous amount of firewood to heat the cabin, but cutting it was no hardship. Chopping wood is both an art and a pleasant pastime. The large, stone fireplace became the center of the happiest conversation in Michigan. Sometimes the girls sang, and sometimes they caught up on their reading. On one very stormy day, Jane Sayers even managed to finish a college theme paper. “I need to get up here more often,” she said.

Because he is a skilled outdoorsman, Frank Sayers serves as a survival instructor for the Civil Air Patrol at home. He conducted several survival hikes for us. Among other things, Frank demonstrated ways to build fires under difficult winter conditions in northern forests. He showed us that the light, peelable bark of the canoe birch ignites easily and burns with a bright, hot flame, and that old birds nests — easy to spot in winter — are also good tinder. Frank showed us how to build simple snares for rabbits or squirrels, and how to build an igloo for emergency shelter. Bob was especially interested in his instructions on using a compass.

One afternoon, our entire group skied or snowshoed out into the woods for a picnic. Though snow fell steadily, we built a huge fire. When it finally subsided to hot coals, we roasted fish on a green willow grill and made biscuits in a reflector oven made of folded aluminum foil. Even the most jaded appetite would have enjoyed fish and biscuits with melted butter served piping hot.

We ate like kings at every meal, and many kings would have been hard-pressed to match our menu. I’d brought along a whole antelope ham, and antelope is hard to beat. Frank had put aside a quarter of a Dall ram for our trip. Anyone who has tasted wild sheep knows its incomparable flavor. After a fishing trip to Florida, Tom had frozen the fillets of several large kingfish, and one evening we had a fish fry none of us will ever forget.

Doris, Isabelle, and Nancy are splendid cooks. A day sometimes started with Isabelle’s sourdough hotcakes covered with wild honey Frank had scooped from a bee tree earlier in the fall. Lunch might be a robust game stew with cuts of Michigan longhorn cheese, and dinner could be a sheep roast with homemade mint jelly and hot blueberry cobbler.

If you guess there was sadness when time began to run out, you’re right. The days passed and only half the things we planned to do actually got done. By flipping a coin, we decided to spend the last day fishing Indian Lake, which is about 23 miles from the cabin. It’s known for walleyes and northern pike.

We drove about 12 miles to pick up Hank Peterson, an old friend of Frank’s, who operates a small grocery store and bar. Hank came to this country years ago because he likes the solitude, good hunting, and good fishing. All during the winter, he hardly misses a day hunting snowshoes or angling through the ice.

“Fishing’s pretty good on Indian right now,” he said, “but we’ll have to use my snowmobile to reach the best fishing grounds out near the middle of the lake.” Indian Lake is several miles across, and the snow on top of the ice was about 18 inches thick.

We must have been a curious sight. Behind the snowmobile, Hank towed our toboggan and dog sled, both loaded with lunch, bait, tackle, and fishermen. About two miles from shore, he pulled to a stop beside a large, brightly painted shanty with a sign identifying it as The Casino. From its interior, he produced a number of odd-looking tip-ups. With these rigs, the line holder works in the ordinary way, but the line runs through a small hole in the top of a wooden box that has no bottom. When the box is placed over a hole chopped in the ice, loose snow can’t blow into the hole and block it.

The boys spudded as many holes as Michigan law allows, the tip-ups were set up, and the hooks were baited. No more than a minute later, the flag on the first tip-up was waving. Bob made a dash for it, but the going was slippery and he fell flat on the snow. The nibbling fish escaped before he could set the hook. But Tom and Park ran a footrace when a second flag tipped up and hand-over-handed a fat walleye onto the ice.

It went that way for about an hour. Somebody was running to catch a fish all the time. Soon we had three walleyes, two northerns, and eight or nine yellow perch. Then Bob pulled another walleye out onto the ice and almost lost it when it slithered from his grasp. “Let’s see somebody beat that,” he said, as he held up a four-pounder.

Nobody did. Unaccountably, as is often the case in ice fishing, the action suddenly stopped completely. An hour or so later, when a stinging wind began to whistle out of the north, we motored back to shore. We packed up next day, reluctantly extinguished the fires, and drove back over the Jong, snow-banked lane. On the way out, a pair of deer crossed our path, bounding gracefully over the snow embankments.

Read Next: A Christmas Bargain: Rabbit Hunting with My Boys Every Day of Winter Break

Because a whole system of blizzards was circulating across Michigan, we only got as far as Ann Arbor before deteriorating driving conditions forced us to check into a motel. It was New Year’s Eve, and merrymakers were beginning to gather, but we didn’t hear any of the merrymaking that followed. All of us were just too tired. The cost of our entire holiday was less than our bill for one night’s lodging and a New Year’s Eve dinner in the Ann Arbor motel — less than $100 per family. A white Christmas like ours is a happy holiday nearly anyone can afford.