Even though—or maybe because—I live along eastern Montana’s Milk River, I’ve felt for decades that its reputation as a big-buck destination was undeserved.

That reputation was both initiated and perpetuated by the folks at Realtree, the Georgia-based camouflage company, who realized 25 years ago that the Milk River had the right ingredients for television. Its whitetails were abundant, accessible, and decently antlered, but mainly they followed stage directions better than most day-raters with a Screen Actors Guild card.

The Milk River’s whitetails file out of bedding areas in cottonwood galleries and overgrown fields into irrigated alfalfa plots in the early evening, almost on cue. That tendency allows hunters to sleep in, get to treestands or ground blinds in mid-afternoon, and intercept deer just as the prairie sunset fires up eastern Montana’s big sky.

In other words, their habits are made for television, and for two decades, the Realtree Outdoors TV shows brought viewers season after season of Milk River whitetails in the hands of Bill Jordan, David Blanton, Michael Waddell, and other hosts. Along the way, the Milk River became synonymous with big bucks, even it was a rare deer that broke into the “monster” or “giant” category, two terms thrown around pretty loosely by TV hunters. But legions of Realtree fans descended on the river, all expecting to see a Booner behind every scabby cottonwood tree.

Deer Hunting Montana’s Milk River

For those of us who lived along and hunted the Milk, the reward has been “giant” numbers of whitetails, not necessarily trophy-class bucks. When conditions are good—meaning gentle winters and summers that end with an early frost—the irrigated bottomland and associated cover becomes a deer factory, and in some fields, 100 to 200 whitetails might feed in the open during legal shooting hours. Some years, there are way too many deer for farmers and ranchers, and Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks issues liberal antlerless deer permits. One year I had six doe permits, and I filled them all in the bow and rifle seasons. Another year, each hunter could buy up to 10 late-season deer permits, and my friend Mark and I killed 20 deer in one long and cold January day. Some of the “antlerless” whitetails we tagged were bucks that had dropped their antlers.

The two factors that limit deer numbers are crippling winters—it’s not uncommon to see 30-below for several weeks straight here, a season Team Realtree seems never to experience—and EHD, the hemorrhagic disease that is spread by a biting midge. EHD runs through the Milk River like wildfire in drought years with late frosts; in 2012 we lost 95 percent of our deer in a fortnight. My alfalfa field looked like a Civil War battlefield, and the only thing to do was to drag sun-bloated carcasses into the river and hope the anemic current would carry them away.

Milk River bucks tend to be light-antlered, with long tines but short main beams. But every few years, a big buck will show up, looking like a Saskatchewan whitetail, with heavy beams and dark, chocolate-colored tines. I look for just such a buck every year, usually starting in bow season and for a few sits during rifle season. But I’m a mule deer junkie, and I’d rather roam the adobe hills and remote drainages above the Milk in search of a bruiser muley than sit fieldside waiting out a whitetail.

This is my method of hunting whitetails, by the way, from the ground. The wind is such a factor here, and can switch overnight, that hanging stands can be a waste of time. Mainly, though, I like the challenge of sneaking through the orchard grass and ash groves to get in range of a wary whitetail. But, as many nights as I’ve waited over the years, a bruiser-class buck has never shown up. Until this year.

EHD and Drought in Montana

The West has been profoundly dry for the past two years, but few places have been drier than my homeland of northeastern Montana. We got only one measurable snowfall last winter, and no springtime precipitation. At all. Farmers’ wheat crops shriveled in the fields, and if it wasn’t for a week of wet weather in August, most of our rangeland would have burned up under blowtorch winds.

That August green-up saved our deer, too. But they were concentrated around any available water, so when EHD arrived, it killed whitetails by the dozen. I found 11 dead deer on my property on the opening weekend of pheasant season, most of them bucks. A few mule deer succumbed, but whitetails took the brunt of the mortality. FWP cut the number of antlerless permits by 2,000 in my region, and I closed my property to all doe hunting.

We have too many mule deer for range conditions, so I concentrated on filling mule deer doe tags and looking for a big muley buck. More out of curiosity than purpose, I sat in our field on the Milk River one evening in late October, shortly after a hard frost killed the EHD-carrying midges, and was happily surprised at the number of whitetails I saw. Several dozen does and a couple of young bucks.

So when my 17-year-old daughter said she was going to go sit that same field a week later, I told her not to be in a hurry to pull the trigger. You never know what could feed out in the open in the last few minutes of legal light.

Here is the text Iris sent me that evening: “Damn it. Very nice buck here, tried to sneak up to the edge of the field but spooned [sic] them last minute. I’ve got my eyes on this one though – very nice deer.”

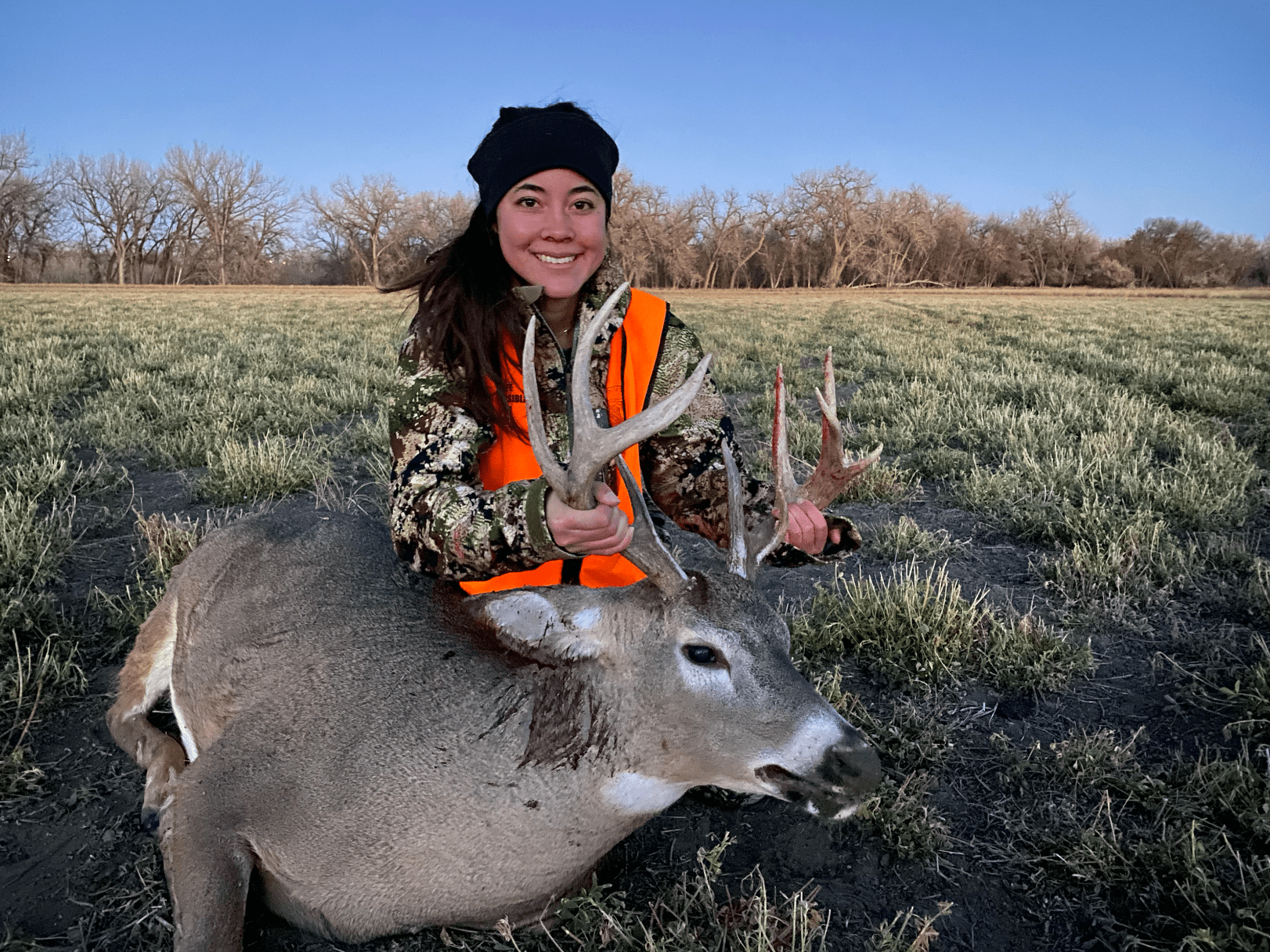

The real evidence of the quality of the buck was that she prioritized deer hunting over everything but schoolwork and running, and a couple weeks ago, as I hunted elk in the Missouri River Breaks, she sneaked into the fringe of our alfalfa field. She saw three nice bucks feed out of the woodlot, and as she told me later, took the one that offered her the best shot. It’s a beautiful mature whitetail, with a crazy palmated antler and a drop tine off the main beam. Significantly, it’s the first time she’s done it all, from figuring out the approach to the shooting distance to making the shot and then field dressing. I got there just in time to help load the deer in her pickup.

A Last-Light Opportunity

Iris reported two details that caught my attention. First, she counted more than 50 does and yearlings in the field, which meant good survival from EHD. Second, she said that the other bucks were similar in size to the one she killed.

The next night, I was on the edge of the field, glassing with a spotting scope and binocular. A heavy 4-point caught my eye, and I was talking myself into shooting him when I saw movement in the woods behind him. It was another class of buck, altogether. Tall and wide, with an upthrust of walnut-brown points, he never gave me a shot or even a great look before darkness covered my exit.

The next night I saw him in all his glory, and decided that was the deer for my season, maybe many seasons. He looked to have five points on a side, but his height and width were way out of normal for the Milk River, and he also had respectable brow tines, a rarity for the local deer population. He was too far away for an ethical shot, but the more I watched him, the more he haunted all the times I couldn’t watch him.

That included a trip out of town to watch Iris run a regional cross country meet and tour colleges. The thing about the Milk River is that there’s abundant access through the state’s Block Management program. And plenty of landowners allow hunting with permission, myself included. Would that deer wander onto a neighbor’s place? Would someone get wind of this “monster” buck and cross our fence? My worst fears were realized on my return. A trespasser had driven into our fields while I was gone.

That night I sat the field again, and saw four mature bucks but not “the one.” The next night my friend Brooks Hansen was due to arrive to hunt with me, and I wasn’t sure I’d get another chance.

Brooks was interested in mule deer, but as many deer as we assessed, we couldn’t find what looked to be a mature buck, probably because the drought had suppressed antler growth. So I took Brooks to the alfalfa, telling him all about the big buck. We waited for two hours, as the darkness crept out of the timber. Just as we were about to leave, I saw the buck briefly, birddogging a doe. Too far and dark for a shot, my heart nonetheless soared. He was still alive!

Same thing next night, and the next. He showed up just at the end of legal light, but a long way off. Would he ever slip up?

Poor Brooks. He became less of my guest and more of my hostage, since I had told him that I’d like a try at that big buck if we got the chance. Night after night, he waited for me to notch my tag while he saw plenty of bucks he said he’d be thrilled to kill. He didn’t want to take a chance on blowing up the field in case “my” buck was on his way.

Finally, on the second-to-last night of Brooks’ hunt, we edged into the field to accommodate a northwest wind, and shouldered into a red willow stand. Buck after buck filed out of the timber, and finally I spotted the big boy, nose to the ground chasing a doe. Damned if that doe didn’t pull him into plain sight. I was ready, my rifle on a Spartan shooting rest atop a tripod. I moved slightly to ensure I wasn’t going to shoot a willow trunk while Brooks whispered the range to the buck: “276. 255. 244. 232.”

I waited for him to stop, and took the 236-yard shot. I was shooting a .280 Ackley Improved, and the 155-grain Federal Trophy Copper seemed to take a full minute to cross the field, but the hydraulic “thuuuump” of the bullet making contact confirmed the hit. The buck wheeled and ran back toward the timber. He made it 50 yards before falling dead.

A Lifetime Deer

I’ve killed a lot of whitetails in this field over the years—dozens of does and a couple of mid-sized bucks—but nothing like this buck. His tines. His split brows. His bladed points.

Finally, the hostage situation was resolved. Would Brooks head into the hills for one last look for a mule deer? Actually, yes. All morning he looked over more deer for a reason not to return to the Milk River alfalfa. He couldn’t find one, so on his last night we snuck along the bank of the river. He had seen two whitetails that interested him, one tall and the other wide.

The wide buck pushed a doe just after sunset, and Brooks was waiting to close the deal. As we were field dressing his buck, Brooks told me that being my hostage wasn’t that bad. Also, he said, he had a confession.

Did he do something unspeakable in the guest room? Did he break another glass? Did he get permission to hunt the neighbor’s field?

“While you were working today, I snuck in and scored your buck,” he told me, a little timidly. I had told Brooks that I have never scored an animal, not because I’m against the idea, but mainly because I don’t especially care.

“He’s 169, and that was being really conservative with measurements,” he told me. I was secretly thrilled. My best-ever whitetail—killed on my family’s Missouri farm the year we sold it—is probably in the 180-class, so to have killed a deer almost of that dimension on my land along the Milk River swelled me. It made me feel—just for a fleeting moment—that maybe the Milk River’s reputation is justly deserved, after all.