That frosty Mexican dawn on the Sonora desert looked like any other one — but it ushered in a day that we can never forget. The desert teemed with white-tails and muleys. Even Nelson — who had marked off the hunt for a bust — came in for the surprise of his life.

I have seen some gloomy characters in my day, and I have also seen some who were depressed, but I believe the gloomiest and bluest citizen I ever laid eyes on was Ivon Nelson when he rode into our camp by the little well in the Sonora desert late that December evening.

His eyes were glassy with fatigue and his broad brow was beaded with the sweat of pain and fear. He looked like a man who had just come out of a Communist torture chamber, where his toenails had been torn off with pliers and burning slivers thrust in his quivering flesh. He slid groaning from his horse and collapsed on the ground.

“See anything on your way in?” I asked politely.

”Get that damned goat out of the way,” he ordered, ignoring my question. “He’s just about killed me now and if he gets a chance he’ll step on me and finish me. . . Take a look at my hind end, will you’? .. he asked as he lay on his stomach. “I think I can feel bloody bones sticking out of my pants, but I haven’t the strength to look!”

I led his horse away, tied it to a tree, and started unsaddling it.

“See anything?” I asked again.

“See anything? Now don’t be funny. . . Well, come to think of it, I saw one deer track, a track made by a one-legged deer that hopped through this damned country sometime last month.”

I hobbled the horse, turned him loose, and gave him a crack on the fanny. He took an awkward jump in Ivan’s direction. Ivon staggered up with creaky agility and dodged behind a tree.

“What did I tell you?” he demanded. “That horse wants to kill me.” Then gingerly he sat down on a sleeping bag.

“Have a beer?” I asked.

“If you bring it to me!”

I got into the case of split pints of the wonderful Mexican Carta Blanca we had picked up at Pitiquito. It had been wrapped in canvas and was still cold. By the time Ivon had finished it, some color had come back into his ashen cheeks.

Jose, the Mexican lad who had ridden over from the ranch with Ivon, winked at me. ”The bald-headed one has a sore hind end.” he told me.

Just then we heard the brush popping and Dave and Santiago hove into view. Dave, who was used to riding, hopped spryly off.

“See anything, Ivon?” he asked.

“No,” Ivon groaned.

“Well,” said Dave, “I saw three does and a heck of a big buck. Couldn’t get a shot at the buck, though.”

“You’ve scared all the deer in country,” Ivon said.

Then Heap and Zefarino came jingling up. Heap looking dejected Zefarino grinning.

“I’ll tell you the worst before this Mexican cowboy does,” Heap said as he dismounted. “If you heard all those shots it wasn’t a new revolution. It was just me missing bucks. I shot at four of them — all had moss on their horns and were five years older than Moses. I shot twenty shots and I didn’t get a hair. The last one just stood there while I used my last cartridge on him. Then this guy, this funny fellow,” — pointing a finger at Zefarino — “handed me a bunch rocks.”

Zefarino screamed with laughter, turned to me, and pointed at a saguaro about forty yards away. “The last one was that close,” he told me. “The big fellow waved his rifle like a flag!”

“Many bucks around now?” I asked him.

“Many, there are many. They chase the does and are easy to see. . . . Tomorrow, you and the boys and I will go out and we’ll kill all you want. Then we can go hunt quail. O.K. ?”

Dusk was falling now. All the gringo horsemen were tired, but none so tired as Ivon. While the others had ridden in, my two sons and I had driven over to the campsite, put up tents, and prepared supper. As we ate we could hear the horses, browsing on the ironwood trees, and the sleepy quail clucking down the arroyo. All around us was the smell of the desert night.

The next morning Zefarino and I piled out before daylight — I out of an eiderdown sleeping bag and the luxury of an air mattress, Zefarino out of a pile of horse blankets. For the Sonora desert, it had been very cold and a thin skim of frost lay on the ground. I washed my face and combed my hair in front of the mirror we had put up with a nail on the trunk of a big mesquite. Zefarino completed his toilet by putting on his shoes (no socks) and shaking. In a moment we fed the coals of the fire with fresh ironwood and the waxy branches of ocotillo so that it flamed up as if we had dumped gasoline on it. Presently the coffee was boiling. the bacon was sizzling, and the pilgrims, including my own two gummy-eyed sons, began to stagger out of the tents and contemplate the fact that this was another day, a glorious winter morning on the desert coastal plain of the Gulf of California.

“Are you going to ride out or walk?” I asked Ivon as we ate.

”Ride? Me!” Ivon snorted. “Listen, I slept on my stomach all last night. Even if there were deer in this Godforsaken country I wouldn’t ride. I’ll take my little rifle and with it I’ll take a little walk. I won’t see a thing because there isn’t anything to see, but at least I’ll not be tortured.”

“Don’t be discouraged,” Heap said. “I’ll testify to the fact that there are at least four bucks in the country. I missed that many.”

So we drew up our plans.

Zefarino, Jerry, Bradford, and I would hunt to the northeast. Heap and Jose would hunt to the southeast, and Dave and Santiago would go southwest toward the gulf. We didn’t get too early a start because lunches had to be put up, stirrups adjusted, saddle scabbards tied on. By the time Zefarino, the boys, and I rode away, the sun was over the mountains to the east and casting long, black shadows from saguaro and ocotillo.

None of us knew it, but the most fantastically lucky day on deer I have ever seen was about to begin.

A Sharp Eye for Game

We had ridden slowly upwind for perhaps a mile and a half, Zefarino in the lead with me, and the two boys to the rear, when that eagle-eyed Zefarino held up his hand for me to stop, then pointed.

“Buros!” he said softly. (Buro is the Mexican word for mule deer.)

Across a wide, sandy arroyo, from 150 to 175 yards away, I could see a couple of dim gray forms behind some paloverde trees. I slipped off my horse and pulled my .30/06 gently out of the scabbard to be ready if one of the deer was a shootable buck. Then I got them in the field of my binoculars. In a moment one of them moved and I could make out a big four-point buck watching me from behind the screen of branches.

Related: The Outdoor Life Cover Art Shop

Low brush made it impossible for me to take a sitting position, but I got down on one knee, put the crosshairs of the scope where the middle of his chest should be, and cased one off. We heard the slap of the bullet striking flesh, and dimly we could see the buck whirl and go into a frantic run before I could work the bolt for a second shot. A doe ran to the right, then disappeared into the brush.

“He’s wounded,” shouted Zefarino in Spanish. He touched his spurs to the magnificent bronco he was riding and shot across the arroyo, in the direction the buck had taken, as if he had been fired from a gun. A moment later I heard him shout, “Here he is!”

As I got up on my steed the two excited boys joined me.

“What did you shoot at?” “Did you get him?” “Why didn’t you tell us?”

The buck was lying in a little opening about seventy-five yards from where he had been hit. The 170-grain soft point had struck him right at the point of his chest. It had blown his heart to pieces and had gone almost through him lengthwise. He was a beauty; heavy, burly, sleek, and fat. I have seen better heads, but his antlers were good enough so that no one would need apologize for them.

After we had dressed out the buck and hung him in an ironwood tree, our cavalcade set out again. We saw a couple of does run across a low hill and a little later we jumped a whole herd of does and fawns out of a brushy arroyo. This was probably the harem of some big, wise buck, but if it was we never could see him. The ungallant fellow had probably made a quick, low-headed sneak, leaving the dames to shift for themselves.

Read Next: The .270 Winchester Was Your Grandpa’s 6.5 Creedmoor

Finally we reached the little chain of hills for which we had been headed, hills that in the past when I had hunted there had almost always been good for a shot at a white-tail buck. On the Southwestern desert, the mule deer begin to run toward the last of December and the run was just getting under way. White-tails, though, do not run until February and none of the bucks we were to see were with does. We tied our horses in a little basin in the hills. Since it was up to the boys from now on, I hung my rifle in a tree. Zefarino took off his spurs, as we planned to hunt on foot.

Zefarino took Jerry in tow and I set out with Brad. We agreed to meet about a mile and a half away at the end of the chain of hills.

Almost at once, Brad and I started seeing deer sign, mostly the little heart-shaped tracks of white-tails, but occasionally the big, long track of a desert mule deer. In this mixed-game country, the mule deer stay almost entirely out on the brushy flats, the white-tails in the hills. Brad and I went along quietly, rimming all the little basins. Every time we got to a good vantage point, I’d take out my binoculars and go over the basin inch by inch, trying to locate a bedded buck. Once I picked up a doe and fawn lying below us. We didn’t disturb them and when we slipped off I am sure they had never been aware of our presence.

He was a beauty; heavy, burly, sleek, and fat. I have seen better heads, but his antlers were good enough so that no one would need apologize for them.

About the third basin we glassed yielded results. First I was sure I saw an ear in the brush below us. Then the glass showed me antlers connected with the ear. Then I could make out most of the body of the buck as it lay there about 100 yards away. I handed Brad the glass and pointed. It took him some seconds to see the buck, but finally his eyes widened in delighted surprise. He laid the binoculars down, switched off the safety of the .257, and took somewhat-shaky aim. His first shot went right over the buck’s back.

“You jerked the trigger and shot over!” I whispered.

The buck didn’t have the faintest inkling of danger, so it lay there.

“Squeeze this one,” I said.

Apparently he did, because I heard the bullet strike and the buck bounced to his feet and went out of there. He ran through the brush and then came out onto the open hillside about 200 yards away, his white tail high and glittering in the sun.

Frantically Brad was trying to get off another shot, but I had snatched up the glass and had the buck in the field. I knew it was unnecessary for Brad to shoot again. Just as the buck got into a saddle I could see him begin to stagger and his proud white flag begin to droop. When he disappeared I knew we’d find him within a few yards of where I had last seen him.

Together Brad and I walked through the basin. I showed him the buck’s bed with a big fan of frothy blood and hair where the bullet had gone clear through. We followed the tracks and blood up the side of the basin and into the saddle. The buck lay within a few feet of where he had disappeared — a fine, big desert white-tail with few points but a massive pair of antlers. As he saw him, Brad’s face was a study in ecstasy.

A White-tail — Offhand

When he heard the shots, Zefarino abandoned his hunt with Jerry and the two of them went back for the horses. Presently they came jangling up. We put the buck on behind Brad’s saddle and started to hunt along the rest of the chain of hills, then swung over to pick up my mule deer.

I don’t believe we had traveled half a mile when another white-tail buck jumped up part way across a basin and stood there looking at us.

“Jerry,” I said, “there’s your buck!”

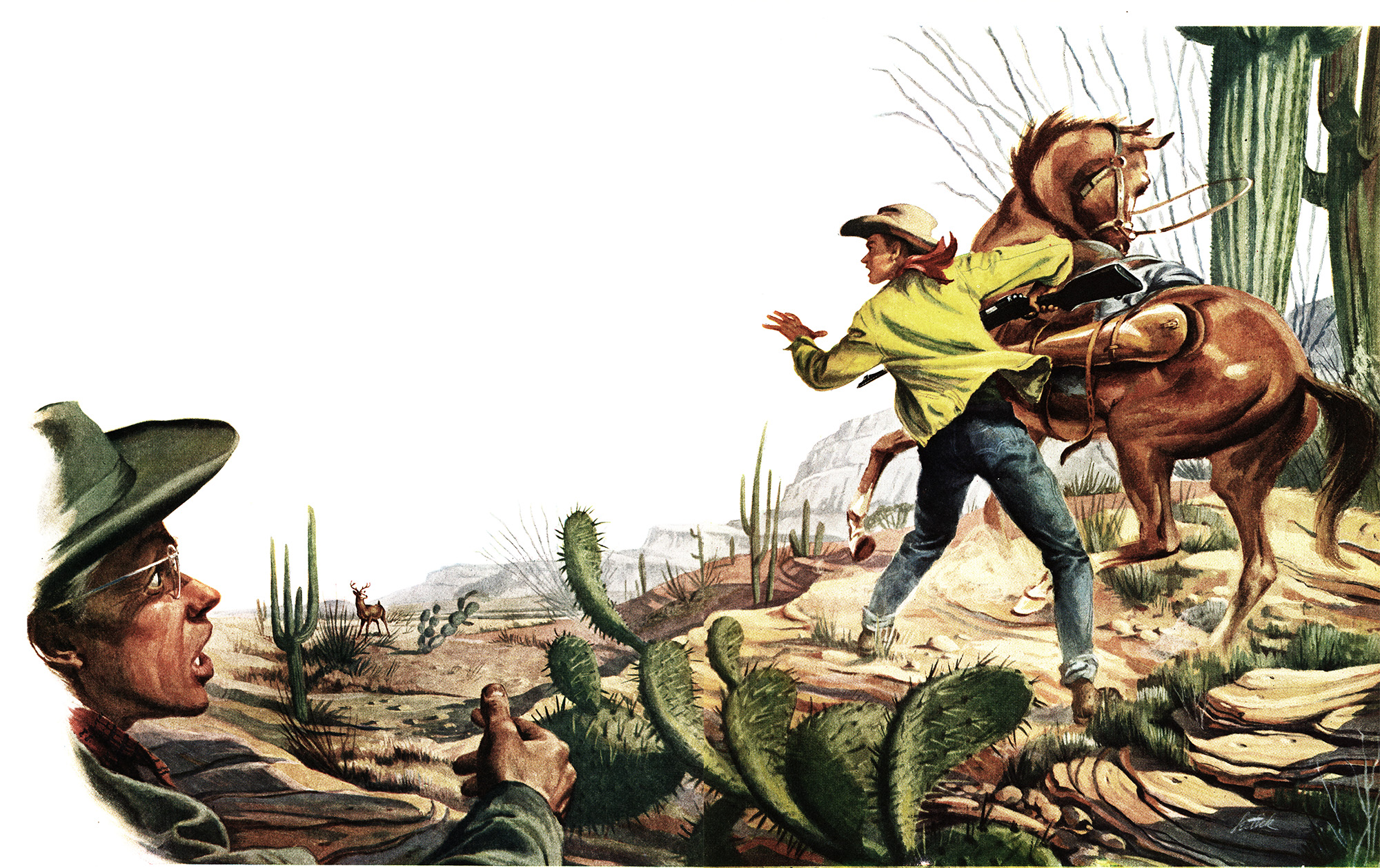

The lad leaped off his horse and jerked the .270 out of the scabbard. With horror I saw he was going to shoot offhand. I didn’t want to disturb him by telling him to sit down, but I was angry because he had forgotten my instructions never to take a shot offhand when he could sit.

Read Next: The Best Hunting Rifles, Tested and Reviewed

But he needn’t have worried. When the rifle cracked, the buck turned clear over in the air and hit like a bag of potatoes.

“Whoopee!” said Zefarino. “That’s the kind of rifle I like. One that has power. One shot and the buck doesn’t move. How do you call it?”

“The .270,” I said.

“The same one you shot the ram with up north, no?”

“The same!”

“With the .30/06 you shot a buck and it ran. Then the smaller boy shot a buck with a .257, and it ran. Now the large boy shoots a buck with his rifle and it is dead in its tracks. How good a rifle, this .270!”

“It shoots a good ball,” I said — “a very fast ball.”

“Like the lightning!” said Zefarino.

While Zefarino and I were engaged in this ballistic discussion, Jerry had galloped like a jackrabbit over to his buck. We joined him, shot a couple of pictures, and then loaded the animal on behind the saddle.

When we reached the tree where we had hung my mule deer, a vagrant thought struck me that it would be a funny gag for me to walk into camp empty-handed. I would tell Ivon that he was right, that there were few deer in the country, and that we had hunted hard all day without a shot. Then, to the merriment of all, Zefarino and the boys would come in with three bucks.

The lad leaped off his horse and jerked the .270 out of the scabbard. With horror I saw he was going to shoot offhand. I didn’t want to disturb him by telling him to sit down, but I was angry because he had forgotten my instructions never to take a shot offhand when he could sit.

But if ever a gag backfired, it was that one. When I got to camp, what should my wondering eyes behold but Ivon seated with his back to an ironwood, nursing a bottle of beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other. In the tree were two bucks, both of which he had shot within half a mile of camp.

Not long after we had left, he told me, he walked out from camp a little way and saw a buck feeding on ironwood. He sneaked up and shot it. Then he started back to camp for a horse to pack his buck in on, came on the other buck, and shot it. Just like that.

When my game-laden cavalcade came winding in, the fire was all out of the gag.

Darkness was falling before Dave and Heap arrived. Heap had used up his luck in finding deer the previous day and had not seen another buck, but Dave had a deer — and also a story.

He had missed his first shot at the buck and had thought it would be his last. However, his vaquero had taken off after the buck, swinging his riata, and presently he called out that he had the situation in hand: to come and kill the buck since it was getting restless. Dave was astounded to find that the lad had his rope firmly on the buck’s horns and had him tied to a tree!

“Oh, heck,” Dave said, “let him run and give him a chance. I’ll take him on the bank of the arroyo!”

According to our Mexican licenses we were each entitled to three bucks, but we had all the deer we could use or conveniently transport. So the next day Ivon and I skinned and quartered the deer while the boys took shotguns and hunted quail, and Dave and Heap climbed a mountain to see the white beaches and flat blue sea spread out before them ten miles or so away.

When we got back to the border, I heard Ivon telling an American customs officer: “You ought to see that country. Damnedest buck country you ever laid eyes on. You can’t throw away a cigarette butt without hitting a deer.”

“That isn’t what you said the night you got in,” I reminded him.

“That was then!” he said.

This story first appeared in the April 1951 issue of Outdoor Life. Unlike other O’Connor stories of the time, it did not contain any photographs.