India holds both a special and tragic place in hunting history. Some of Outdoor Life‘s most influential and legendary tales of hunting come from the jungles of India—including those of Jim Corbett and even Fred Bear. Hunting has been banned in India since the early 1970s, and poor conservation practices, deforestation, and poaching haven’t helped the country’s wildlife. Still, classic hunting tales from India can both inspire and educate us—hopefully helping us take better care of the resources we have into the future.

When it comes to hunting man-killers in India, most people think of jungle cats: tigers and leopards. Sloth bears aren’t usually at the top of the list. However, while on a tiger hunt in Madhya Pradesh, a large landlocked state in central India, Frank C. Hibben was asked to hunt a sloth bear that had killed and maimed several villagers. This story, “A Killer of Men,” was originally published in the March 1957 issue of Outdoor Life.

Sloth bears are about the size of the American black bear, but with shaggier coats and very long claws on their front paws. Attacks aren’t common, but they do happen. In fact, a CBS article published in June 2022 details a fatal attack by a sloth bear in the same region where this story took place.

A Killer of Men

By Frank C. Hibben

IT WAS THE PEACOCK that gave the warning. The bright little eyes of the bird had picked us out immediately, although the foliage was dense and Rao and I were motionless as the stones around us.

The peacock gave a clacking cry, and at the sound the bear turned toward us. The animal’s black lips wrinkled up in the beginning of a snarl. The panting stopped for a moment. The yellowed teeth, dripping with saliva, opened wide and snapped shut with a sharp noise. It clicked in my mind that this same animal had already killed three humans.

We hadn’t come to this part of India to hunt bears—not even a certain sloth bear. This was tiger country, and Rao and I, only a few hours before, had been busy tracking down a very large male tiger near the neighboring village of Arjuni. There was other game, true, but tigers were the main attraction. The week before, Rao and I had killed a large tigress and a male which ran with her. These two tigers had turned man-eater and already had accounted for several human victims. Having done the good deed of shooting the two man-eaters, we had moved here to the Arjuni area to hunt a big male tiger.

We were in one of the most remote portions of the plateau of east-central India. My wife, Brownie, and I had gone to considerable trouble to get here. We had flown from Bombay to Nagpur, where we picked up our Hindu guide, Rao Naidu of the firm of Allwyn Cooper Limited. Allwyn Cooper originally was a firm dealing in teak and other tropical woods. However there had been so many calls upon it by sportsmen who wanted to shoot a tiger that the jeeps and personnel of the firm had turned to big game hunting entirely. Rao Naidu had already killed more than 80 tigers and is considered one of the top tiger men from Ceylon to New Delhi.

Rao had suggested that we take the long train ride from Nagpur to Raipur so as to get into the tiger jungles of Madhya Pradesh. At Raipur we picked up a jeep and trailer loaded with such bedding and equipment as we might need for a three-week hunt. We also picked up eight Hindu boys as camp assistants, skinners, and trackers.

From Raipur, Rao drove the jeep and trailer 100 miles or so along forest roads which the British had years ago built into the heart of the teak forests north and east of Raipur. As we jounced along, the road steadily degenerated into a jungle track with the dust churned powder-dry and a foot deep by the wooden wheels of the bullock carts hauling out teak and bamboo. As he manipulated the jeep through the suffocating clouds of dust, Rao explained that we had come all this way not just for tigers but for one particular tiger.

Rao was somewhat annoyed when on the fourth evening of our stay at Arjuni a little man broke into our conversation at the government rest house which was our camp. The fellow wore the usual white rag around his buttocks and was otherwise naked except for a distinctive cap which had a visor and a flap of cloth behind. It was his only badge of office as being some kind of a minor official in the district. He saluted smartly, in keeping with his cap, and asked if he might speak with the sahib. My wife and I thought the man might be applying for a job or that he had news of our big tiger, but as he talked in Hindustani it became clear that he was asking for something.

After Rao had listened for several minutes, he turned and translated for us: “This man has walked over from the village of Gindoli. He asks us to come there and shoot a killer of men.”

“Another man-eating tiger?” I asked.

“No tiger at all,” Rao said slowly, “but a sloth bear.” I had heard of the Indian sloth bear before. I knew that its name was derived from the fact that it has very long claws on its forepaws and in that respect resembles a sloth. It uses these claws for digging up roots and small rodents, which constitute the major part of its food. The sloth bear is a handsome beast with long black hair on his body and a white V-shape marking on his chest. I remembered particularly seeing this light-colored chevron on a sloth bear I once watched in a zoo.

Our head bearer led the man from Gindoli village to the rear of the cottage to have some tea after his long walk. Then Rao said, “Sloth bears are not usually dangerous; but when they are bad, they are very bad.” Rao spoke Oxford English with a Hindu intonation which made it sound like a chant.

Next Rao shook his head as though in consternation. Apparently the man from Gindoli had told him more than he had translated for us. “Perhaps we could put off our hunt for the big tiger a few days,” Rao suggested. He turned to Brownie. “Would you like to see Gindoli? It is a beautiful drive.”

I knew this was a subterfuge and also knew that it would be no beautiful drive—not with those suffocating clouds of dust and the road jammed with bullock carts full of teak logs. But I did want to get this sloth bear that killed people.

WE DROVE the 20 miles or so to Gindoli the next day. The Raipur teak forests never cease to amaze us. The country was rolling and almost flat. As this was in March, the forests were dry and had the appearance of a relatively open New England or Pennsylvania woods in the fall of the year. Along the nullahs or watercourses scattered about the low hills were clumps of bamboo and thicker growth. Every few miles were small villages surrounded by cleared rice fields now empty and brown. This was the middle of the dry season.

At almost every bend of the rude road were peafowl dusting themselves in the ruts. We stopped once to shoot two of the birds for supper. A peacock is about the size of a turkey and delicious eating. Our trackers were very eager to have us shoot the big males so they could use the long tail feathers for dance decorations and fans, but we found the cocks wary and hard to approach within shotgun range.

But there were also jungle fowl (which are the ancestors of our own chickens), partridges, green pigeons, and several kinds of doves. Unless we were trying to be quiet while in pursuit of bigger game, we seldom had difficulty shooting enough birds for the pot on any drive in this area.

The region of Gindoli village was more barren than most of the country. Here the sandstone rocks of the plateau were bare of soil in many places. Some geological upheaval of long ago had created two low ridges of jumbled rock perhaps half a mile apart. Between these was a long basin. In this depression the village of Gindoli lay.

As our jeep labored over the rough rocks of one of these ridges and down into the hollow, all the villagers came forward to look at us. The men bowed low to make us welcome. Women with tattooed faces and rings in their noses smiled graciously upon us. Naked children pressed forward to touch the fenders of the jeep.

Rao began a spirited conversation with the elders of the village. Our two trackers, Manchu and Sardarsingh, were talking with several young men of the village, apparently the hunters of the group. One of these men carried an ancient muzzle-loader that obviously would not fire. But it gave the owner considerable prestige, nevertheless. He was gesticulating and arguing with an air of authority.

My wife and I examined the surroundings of the village while these long talks were in progress. The houses and fields of Gindoli suggested extreme poverty. It was difficult to see how any people, no matter how industrious, could wring a living from this barren place.

About a quarter of a mile below the village was a small pond. As we walked down to examine the place, a flock of teal jumped up and circled away. White egrets stalked in the mud around the water. I noticed a tiger track at the edge of the pond. The animal had come in to water the night before. I could not understand why these people, who lived every day with tigers and a dozen other hazards, should be afraid of a bear.

When we returned to the group around the jeep, Rao led a young man forward to meet us.

“This is Daru of Gindoli,” Rao said by way of introduction. “He was hurt last year.”

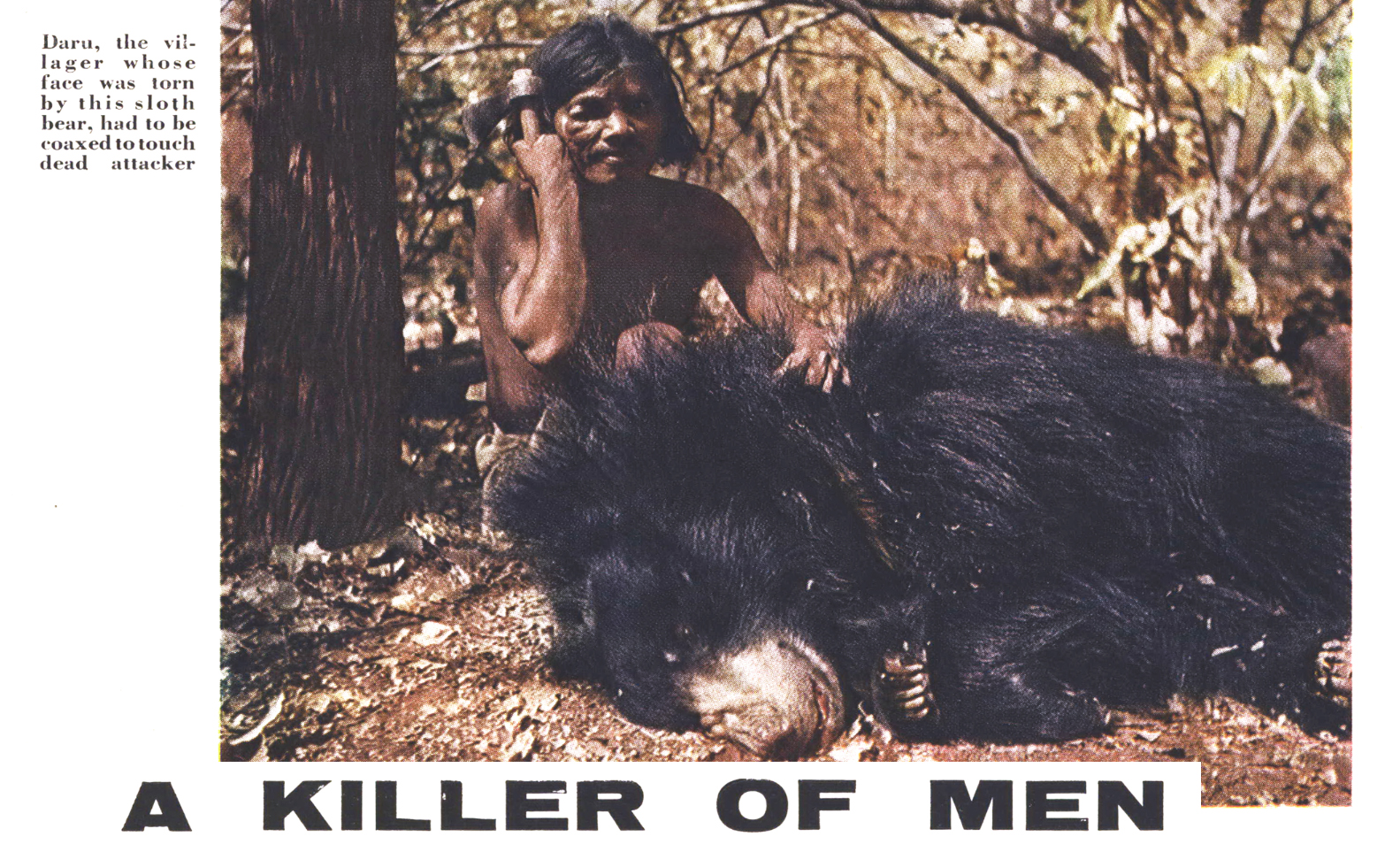

We scarcely heard what Rao said. We were staring at the man’s face, or what had been his face. His cheek and ear were gone so that the naked bone of his jaw showed through a crack. One eye had been torn away. His mouth, ripped open at the corner, had healed askew, and with a horrible star-shaped scar on the side of his chin.

Rao said, “This man was attacked by the male bear. He put betal juice on the wound and did not die.” We had to marvel at the stamina of a man who’d survived those awful wounds.

“There are three sloth bears near the village,” Rao was saying. “There is a female, a young bear, and an old male. The female and the old male have killed two men and one woman of the village. Two days ago another woman was attacked. That is when they sent for us.”

“Let’s shoot them, then,” I said with enthusiasm.

Rao smiled in his quiet manner. It was obvious that I had no idea how one went about shooting a sloth bear.

RAO WAS ALREADY issuing orders to the young men of the village. The village headman was waving the small hatchet he carried and ordering the young men to start off on the hunt. Four of these steadfastly refused. Some of the women also joined in the argument. The four young men sat down on the ground· to emphasize their determination not to move. Rao shrugged and we started off towards the rocky ridge on the far side of Gindoli with only 10 men and two or three boys.

“Some of the men are afraid to help us hunt the bear,” said Rao somewhat needlessly.

One of the villagers carried a charpoy, a native bed which is made of a wooden frame laced with cords. Rao and I carried our rifles and Brownie brought along the cameras. We mounted the rocky slope and crossed it, entering an area where the trees were thicker in patches, with occasional glades of bare rock where the soil was too thin to support vegetation.

It was in one of these bare, sandy spaces that I saw for the first time the track of a sloth bear. The track was impressive—about the size of a grizzly track, with the marks of the long, arching claws of the forefoot well out beyond the toes.

“The bears have been eating the fruit of the mohwa tree in the valley beyond here,” Rao explained. “They water at night at the pond below the village. Any humans that they meet they attack.”

The men from the village stayed in a tight group and talked in low tones as Rao directed their hoisting the charpoy into the forked branch of a low tree. The bed was lashed in a horizontal position and Rao, Brownie, and I climbed up to the platform. It was late afternoon as we took our position. From the platform, or machan, we could see across one of the little open spaces of bare rock for perhaps 100 yards. Beyond this the mohwa and sal trees grew thick to form an almost impenetrable wall of vegetation. The mohwa trees at this time of the year produce a white fruit the size of a small crab apple. This fruit drops off the branches every night and covers the ground with a fragrant-smelling layer that looks like a carpet of popcorn. The mohwa fruit is eaten by almost all the animals of India, including humans. A Gindoli woman gathering mohwas had been killed by the big male sloth bear only the month before.

As Rao signaled the drivers to move off, they walked reluctantly and still in a group. Our two trackers, Manchu and Sardarsingh, tried to marshal them into some semblance of order, but it was obviously difficult. The plan was for the line of men to circle wide and form on the far side of the mohwa thicket, then, with shouting and noise, drive the bears toward us. This driving technique is one standard way to hunt tigers. I’d already seen the villagers of Arjuni walk through the thick brush to drive man-eating tigers up to us. Certainly these Gindoli villagers weren’t going to be afraid to drive bears in the same way.

But Rao shook his head as he saw the villagers leave. Brownie and I were occupied with the sights and sounds of the jungle in the late afternoon. A flight of parrots flew past, their bodies emerald-green against the evening sky. Peafowl screamed in the distance. A spotted deer barked like the baying of a hound. Far off to the side we saw the spiral horns of a big-bodied antelope called the blue bull as it broke through the trees and dashed away. But that was all.

After perhaps two hours of waiting, we made out the bobbing turban of Sardarsingh our tracker. Manchu was a few paces to one side of him, moving along striking the boles of the trees with the flat of a small ax. Far to the right was a whole cluster of turbans and faces—the villagers. They were still in a group and were coming toward us single file, making scarcely a sound. They looked furtively from side to side as though they hoped they wouldn’t see any bears and would get safely back to the machan.

“Some drive,” I said. “How do these guys expect us to shoot their sloth bears if they won’t drive them for us?” Rao shrugged eloquently.

After the miserable failure of our sloth-bear drive, I expected Rao to give up the project so we could go back to hunting the big male tiger. Rao didn’t even mention sloth bear as we drove back through the jungle night to the government rest house at Arjuni. The next morning as usual he received reports on the tigers from the local trackers and sent the assistant cook to an adjoining village to bring back a half-grown water buffalo for tiger bait. That evening Rao suggested that we take a ride in the jeep.

I noticed as we started out that Rao had mounted a big searchlight on the back of the jeep and connected it by short wires to the jeep battery. Manchu, sitting high in the rear, could manipulate this light from side to side and up and down so as to sweep the walls of the jungle on both sides of the road. This type of spotlight hunting is common and legal in many parts of India. It is used for tigers, leopards, and also horned game.

ON THE LONG and rough drive to the village of Gindoli we several times saw eyes gleam through dry leaves of the teak thickets. Once it was a band of spotted deer crossing the road. Farther on, in the bottom of a small valley where the bamboo grew thick, we saw several widely spaced eyes that gleamed white in the reflected light and then quickly withdrew. “Seladang,” said Rao in a low voice, then translating, “Bison.”

The furtive animals at once crashed away through the bamboo thickets and were gone. We wanted to get one of these blue-eyed bison, but apparently Rao was after other game.

Almost the whole night we circled the village of Gindoli with the jeep in low gear and the searchlight sweeping first to one side and then the other. We moved almost silently over the little jungle paths. There was only the crunch of the big teak leaves beneath our tires, the call of the night birds, and the occasional movement of animals in the dry undergrowth.

It was toward morning that we saw a pair of eyes that shone like two white stars through the stems of a clump of bamboo. Rao brought the jeep to a cautious halt and grasped my shoulder with one hand. “It’s a sloth bear,” he said under his breath. “Shoot him between the eyes.”

I had visions of making a spectacular kill. How pleased the people of Gindoli would be when we brought in the body of the deadly sloth bear shot neatly between the eyes by the skillful American hunter.

I climbed cautiously from the jeep and advanced a few paces to the bole of a small tree. I knelt by the side of this so that the beam of the spotlight came over my right shoulder. The two lights which were the bear’s eyes blinked out in the darkness and then on again. “Hurry,” hissed Rao from the jeep.

I looked through the scope sight for night shooting. I could barely make out the outline of the bear’s head and the bulk of his body behind. I centered the crosshairs of the scope between the two gleaming eyes. Suddenly the head turned. His whole body was shifting to the side. I swung the scope to the left where the dark form was moving and pulled the trigger. At the crack of the shot there was an answering splat of noise in the thicket where the bear had disappeared.

“Did you get him?” Rao asked tersely.

“I don’t know,” I groaned. “He turned and ran just as I fired.”

Manchu meanwhile had sprinted over to the bamboo clump where we had seen the bear’s eyes. He returned in a moment shaking his head. He demonstrated clearly by using his finger and one hand how I had neatly killed a large stalk of bamboo instead of the bear. Rao didn’t have to translate.

For two additional nights we circled slowly along the jungle paths of Gindoli but saw no sloth bears. Our beam of light showed us spotted deer, sambar (animals very much like our elk), and more bison. Smaller animals such as civet cats were common, but we never saw the two widely spaced white lights which were the reflected eyes of a sloth bear.

“There is only one way,” Rao announced with finality. “We must give the people of Gindoli courage.”

I didn’t know what Rao meant until I saw him loading into our jeep and trailer some of the tiger trackers and beaters from Arjuni. These were the same people who had driven out two man-eating tigers to us only a few days before, and this at very close quarters in thick jungle growth.

EARLY IN THE MORNING, with those expert drivers piled in the jeep trailer, we bumped over the dusty roads to Gindoli to arrange a final hunt. This was all the time we could spare. Rao had also brought along a couple of minor forest officials who had stopped overnight to stay with us. These men, apparently respected in these regions, seemed to wield considerable authority.

At Gindoli, Rao and the two forest officials mustered out all of the villagers. Some appeared sullen as before but they didn’t hang back. I gathered that Rao was making it plain to them that if they refused to help us drive for the sloth bear, we were going to withdraw and let the bears eat on the populace for another year.

Our Arjuni beaters spoke to the crowd with much chest thumping and gesticulating. Then, with Rao and the forest officials leading the way, we moved off toward the same low valley where we had made the previous drive in the mohwa thickets. Rao took time to translate for us that the large male bear had survived my shot (which was no surprise) and was still feeding in that area. That morning he had been seen. Two women out gathering wood had fled when the bear growled and reared on his hind legs before them.

It was obvious from the first that this drive was going to be a more determined effort. Not only was the morale of the local beaters boosted considerably, but the plans were more carefully drawn. Our two trackers, Manchu and Sardarsingh, made several short excursions into the teak and mohwa thickets with local villagers to examine tracks and places where the male bear had been feeding recently. Rao and the two forest officials climbed a jutting rock to survey the country and twice sent a man up a tall tree to look over the terrain.

We followed, during these maneuvers, a jungle path which led over the rocky ridge beyond the village and onto a rocky shelf beyond. A side valley led from this place down to the pond below the village. It was evident from the sign that the big sloth bear habitually came to water by this route. It was in this area too that he had encountered and killed humans, for the only source of water for the villagers was this same pond.

It was determined to make the drive late in the afternoon, when the sloth bear would be sure to be in the mohwa thickets in the valley, and the drive would move him in the same direction he would normally travel to water in the evening.

Our machan was abandoned in this instance, as Rao thought the bear would see us if we were perched on a platform in this rather open forest. Rao and I took a stand on the ground. Brownie with her cameras was stationed on a rocky shelf behind us. It was behind a jutting piece of sandstone as large as a writing desk. Rao was to my right a few yards, crouched behind a gnarled tree which grew from the rocky ground. Between Rao and myself ran a faint jungle trail. The tracks of the sloth bear showed in the dust of this path. Before us was an acre or so of comparatively open terrain. Beyond that the mohwa trees and vines made a solid wall.

The plans were well made. If the drivers did their work, the bear would run toward us and then between us on the trail he usually took to water.

WAITING FOR GAME in India is a wonder in itself. As the hot afternoon wanes into cool evening, the birds and animals begin to stir. Flights of birds moved overhead to water at the pond by the village. A sambar stag bellowed far off in the jungle. I thought I could hear in the distance the first shouts of the beaters.

I glanced at Rao. He pointed his chin to one side. A doe barking deer was stalking silently past. The little animal turned her fanlike ears backward and forward. She had heard the shouts of the men in the distance. The wild things became quiet now. Men were shouting and thumping trees with their axes. One of the villagers had a little drum of the kind used to celebrate weddings and festivals. This banged incessantly as the drive progressed.

Rao and I tensed as the sounds came close. We could hear the beaters quite plainly. To the right and left the flankers had already moved up to keep the bear from escaping to the sides.

Suddenly I saw a movement just ahead in the mohwa thicket. A dark body was running diagonally toward us. I crouched low behind the sandstone rock and pushed the rifle forward. The moving form was almost at the edge of the open place. With a crash of branches, a large peacock broke cover and flew from the ground. I always marveled that these great birds could fly at all with that long plumage waving behind. Another peafowl broke through the mohwa thicket, scooted quickly across the open space, and circled around us.

We could hear the drivers plainly as they called encouragement to one another. A small tree 100 yards ahead jerked sideways as a driver struck it with his ax. Or was it a driver? They were not that close yet. Another stem shook, then was still. A heavy animal was moving through the mohwa thicket. I thought I could hear its labored breathing.

I tried to make out an outline. There were only the tangled stems of the leaves and brush, the white mohwa fruit rotting on the ground, and the dry leaves. Then a head appeared. I swung the gun quickly. “Another peacock,” I said half aloud. The bright black eyes of the bird had seen us. The cock moved his head jerkily from side to side as peafowl do. The gaudy crest of feathers gleamed green in the late sunlight as the peacock looked first at us and then behind at the thicket. The peacock would fly in a moment. He was simply calculating how close the drivers were. The sloth bear had eluded us again. Our elaborate drive was a dry run.

I glanced at Rao to see if we could leave our blinds. Rao leaned his gun against the bent tree before him. The peacock screamed piercingly. I looked where the bird was bolting from the thicket.

There was the bear’s head. His mouth was half open so that I could see the yellow teeth, the loose lips, the red tongue dripping with moisture. I could just make out the white V on his chest and the black of the body behind. Frantically I thrust my rifle forward and threw off the safety.

At the movement the bear ran again. Apparently he had stopped only for a second when the peacock had warned him. That brief warning was enough. With yelling humans behind him and two crouching humans in front, he would not cross that open ground.

The bear circled the edge of the mohwa thicket. His body made great arching bounds through the thick stuff. Branches and vines ripped away like string before him. Sardarsingh, our tracker, was so close on the flank that he threw his ax at the bear, but failed to turn him.

There was just one small opening as the bear ran in a half circle around me. Even this was studded with upright rocks and scattered trees. There he was-a black form which gathered into a solid mass, then stretched out in another arching leap up the side of the slope and away.

Through the scope sight I could see the shaggy hair of his flank between the trees. He flashed behind a rock. There he was again. I pulled the crosshairs of the sight ahead of the massive chest and pressed the trigger. At the boom of the shot the bear made one more arching leap, then slid on his face and rolled over.

All was excited noise around me. Rao had seized my hand and was kissing it. People were thumping me on the back. Turbaned heads were jumping up and down and there was much shouting.

“Luckiest shot I ever made,” I said with a silly grin. “That peacock almost ruined the show—” But all the others were talking Hindustani, and my own observations were lost.

Brownie came up with the cameras. The man Daru with the horribly torn face came forward to touch the bear which had maimed him so badly. The villagers finally carried the animal in triumph back to Gindoli. Even then most of the women could not be induced to touch it.

All that evening and far into the night a celebration was held to placate the spirit of the bear. The drums boomed and the homemade flutes wailed high and low. Male dancers carrying two-ended drums around their necks dipped and motioned.

I would have enjoyed these things more if I’d been able merely to observe them, but I was the center of the ceremony. The old women of the village brought a brass tray full of some kind of oil and with a burning wick on one edge. With this they made passes around me. They put yellow meal on my forehead and poured oil on my feet until my shoes were soaked through. Finally I was presented with a small coconut as a symbol of the seed of a new spirit passing from the bear’s body into my own.

When we skinned the bear late that night, we found four lead pellets as big as the end of your finger imbedded in the animal’s chest. The crude balls were surrounded by cartilage and apparently bad been fired a long time ago from some muzzle-loading gun. It was small wonder that the sloth bear of Gindoli had sometimes killed men.

Read Next: Jim Corbett’s Rigby Returns to India