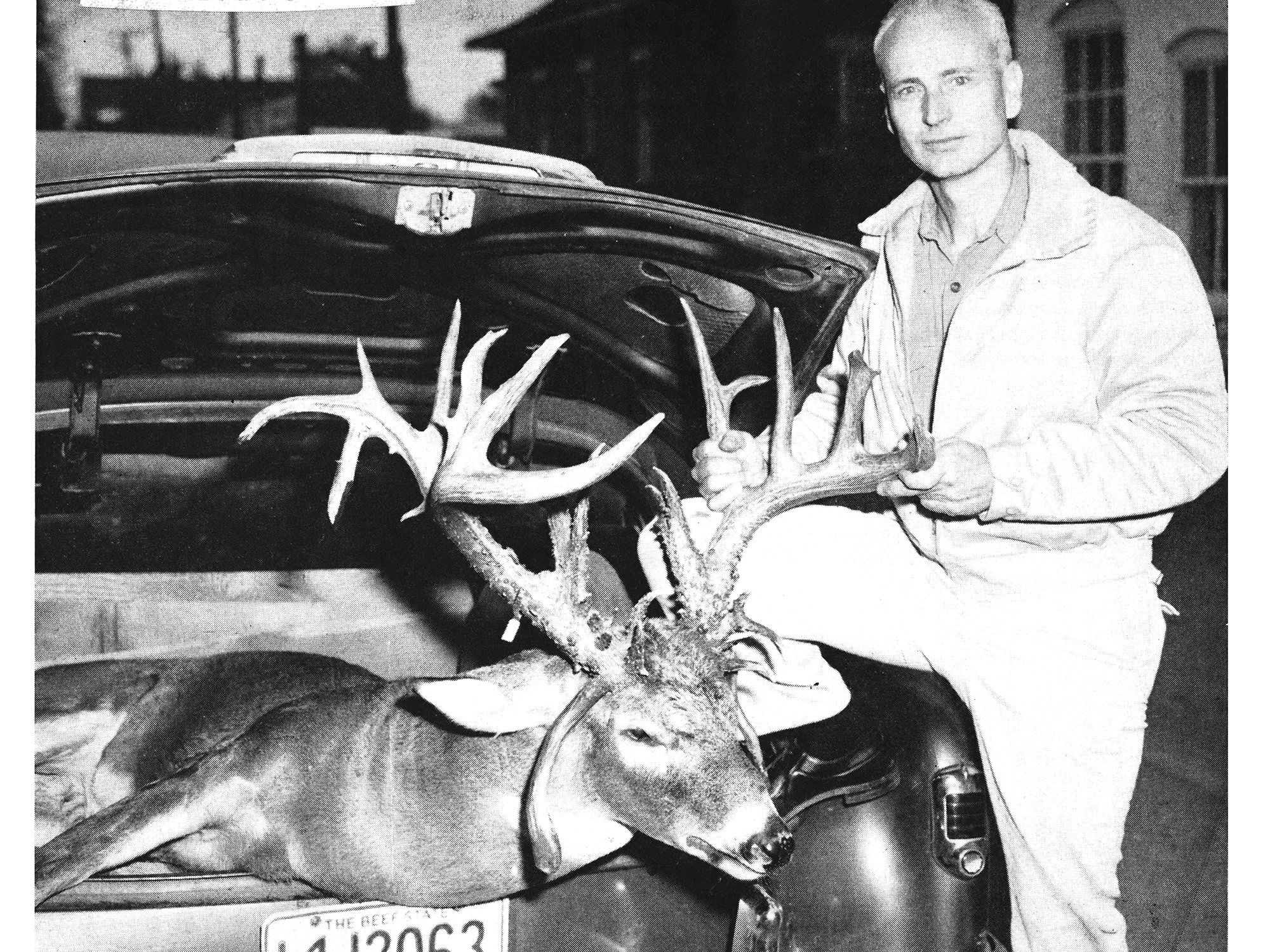

This story, “A Five-Year Stalk,” originally ran in the August 1963 issue of Outdoor Life. The buck remains the 25th largest nontypical whitetail of all time, the sixth largest nontypical whitetail ever taken by a bowhunter, and the second largest nontypical whitetail ever taken in Nebraska. The buck taped out at 284 5/8 inches (gross) with a net score of 277 3/8, according to the Boone and Crockett Club (although Pope and Young recorded them as 279 7/8). The antlers are now owned by Bass Pro Shops.

THE FIRST TIME I saw the deer I made myself a promise. I’d hunt him until I hung that strange and magnificent rack on my wall, no matter how long it took, unless another hunter killed him first. I didn’t guess then that I was taking on a five-year assignment and the most fascinating outdoor quest of my life. Before I was through, I’d have a liberal education in the almost incredible wariness and stealth by which a big whitetail buck survives the hunting seasons.

I met him first in October 1958. I was hunting in my favorite area, on the farm of a friend, Dan Thomas, along the Platte River south of Shelton, Nebraska, 30 miles northwest of my home in Hastings where I worked as a salesman for a meat-packing house. I was carrying a 57-pound bow and three arrows. I’m 36, took up bowhunting seven years ago, and have not used a gun for deer since.

I had crossed a cornfield, on the watch for fresh sign, and had stopped at a fence to look over an adjoining alfalfa field and the timbered river bottoms beyond. Ready to move on, I saw a band of five or six whitetails break out of the timber and run straight for me. The lead buck was tremendous. I had seen nothing like him.

His rack was big and massive, and was the queerest, most deformed set of deer antlers I had ever looked at. There were heavy, spraggly points, long and short, growing from the main beams in all directions. Strangest of all, he had two long prongs curving out and down on either side of his head between eye and ear. They extended below his jaws, giving him an odd, lop-eared appearance.

I knew I was looking at a dream trophy, a nontypical whitetail big enough to go well up on the record list, with antlers the like of which I could never hope to see again. At that, I didn’t realize how good he really was.

A deer trail crossed the fence where I was standing, but I was in the open. So I risked a couple of careful steps back and sank down on one knee in a clump of weeds, an arrow nocked and ready.

The buck was 50 or 60 yards away, still coming like the wind, when he suddenly swerved. I had the wind, and to this day I don’t know what alerted him, unless he had seen movement when I backed up or didn’t like the looks of the weeds that hid me.

He cleared the fence 70 yards from me and stopped, looking directly at me. I knew he wouldn’t come closer, and I couldn’t resist a shot. But the arrow sailed under him. He whirled and ran, leading his bunch in a big circle back into the bottoms.

I retrieved my arrow and started to follow his track. But I knew it was useless, so I went back to my car. I had no interest in any other deer that morning.

Then and there I named him Mossy Horns. I know it sounds corny, but with that irregular rack and those two long tines on each side of his face, it fitted him. I vowed I’d keep after him until that wonderful head was mine.

I knew I’d have a lot of competition. I was not the first hunter who had seen him, nor would I be the last. Stories had circulated in that neighborhood for two or three years, among bowmen and gun hunters, of a big buck with an unusual rack. I had heard them but had discounted them as tall tales. Now that I had seen him, I realized none of the stories had done him justice.

I hunted the river bottoms along Dan’s farm until the bow season closed after Christmas. I had half a dozen chances at lesser deer, but on each occasion the memory of that freak rack kept me from shooting. If I filled my license I’d be through. If I waited, I might get another chance at him. I saw him twice more, but at a distance both times, and then the season ended.

I had hunted alone that fall, but when the 1959 season opened, Gene Halloran, a retired farmer, and Charley Marlowe, a Hastings advertising executive and the only member of our Oregon Trail Bowhunters Club who had killed a deer with a bow up to that time, joined me. I never like to wish partners bad luck, but I couldn’t help hoping neither of them would get the buck I was after.

By that time Dan had his own reasons for wanting the big deer killed. Two years before Dan had planted 50 young spruces for a windbreak about 30 yards from his house. For some reason, the big buck had taken either a marked liking or dislike to them. He tore them apart with his antlers and hoofs and killed every one. There was no question what deer had done it, either, for he left his tracks all over the place; no other whitetail in those parts could have made them.

The Platte bottoms in that area are covered with a dense mixture of cottonwoods, brush, willow tangles, weeds, and grass, and are dotted with countless islands, some small and easy to get to, others big and surrounded by deep water. Many places that can be reached early in the fall become inaccessible later when the sloughs and channels are half-frozen. A belt of wild country with farmland on either side and the shallow river winding through the center, those bottoms are a deer hunter’s dream.

Halloran, Marlowe, and I built tree blinds in half a dozen places, nailing up small platforms 10 to 20 feet from the ground, depending on the trees we put them in and the height and thickness of the surrounding brush. Such blinds are a big help to the bowhunter, since they get him up where deer are not likely to smell or notice him. In the kind of country we hunt, they are close to essential. The cover is so dense it is almost impossible to stalk deer. We have to figure their routes and habits from their tracks and then wait them out.

Unless alerted by movement, whitetails rarely look up. They are used to danger on the ground and look for trouble at that level. They don’t pay much attention to a platform or a motionless hunter waiting overhead. Getting into a tree above them often means the difference between a long shot and a shot at good bow range—or no shot at all.

For all our preparations and many hours of hunting, the long archery season was slipping by without our glimpsing the big buck. I was resigning myself to the fact that he had moved out of the area or might even be dead. We’d had no word of a hunter taking him, but there are always poachers as well as natural misfortunes.

Marlowe finally got a good doe and quit hunting. Gene and I kept at it, but I had about given up hope on Mossy Horns. Then, one November evening, I saw him coming extremely cautiously down a slough 150 yards away. Unless he changed course, he’d walk past me beyond range. He stopped twice at the edge of thickets to watch and test the wind. So far as I could tell, his antlers were identical with those he’d carried a year before. I concluded I had learned something many hunters don’t know. Apparently nontypical whitetails remain in that category all their lives, growing a rack substantially the same shape each year.

I waited until he was beyond me, with a thick screen of brush between us, and then started the most careful stalk I’d ever made. A hard wind was blowing, and he was heading into it. By keeping off to one side with brush between us, maybe I could close in for a shot.

I tiptoed after him for half a mile. He stopped several times, and each time I waited. Three times he rubbed his antlers vigorously against a bush, and while he was doing so I sneaked closer. I had him in range twice, but there was too much brush in the way.

Finally he stopped again, at the border of a thicket, alternately standing quiet and alert, then fighting a bush with his hard and polished antlers. I inched in until I was 25 yards away and was slipping around a willow clump to shoot when a dry twig broke under my feet.

The buck didn’t look, stomp, or snort. He went out of sight in the brush in one crashing bound. Well, I reflected, no deer lives to reach that size without learning all there is to know about avoiding danger.

I saw him once more that year, on the last evening of the season, as I was coming up from the bottoms at dusk. The light was almost gone, but I made out the white throat patch of a deer, and then the huge antlers of Mossy Horns took shape in the gathering dark. He was standing in the open, out of range, calmly watching me. I stopped to stare at him, and when I moved he whirled, and his upflung flag waved derisively, then faded out of sight at the far side of the field.

“O.K., Mossy,” I muttered under my breath. “Next year it will be different.” It would have been, too, but for a piece of typical deer-hunter impatience and a blunder on my part.

That fall of 1960, our hunting party grew to four. Del Austin, a warehouse manager from Hastings and an enthusiastic convert to bowhunting, joined Marlowe, Halloran, and me.

I had kept track of the big deer all summer. Dan saw him about every three or four weeks, never far from his hangout on the Platte bottoms, and when the season opened on September 10, we all believed we had his habits figured out.

There was one particular spot in which I had faith, the corner of a cornfield bordering the bottoms. I had found his fresh tracks there three or four times toward the end of summer and concluded it was one of his regular crossing places. So I built a blind in a nearby cottonwood and resolved to stay in it until he came along.

I waited in that blind every chance I got for seven weeks, growing more and more impatient. Then, one cool afternoon toward the end of October, two bucks strolled out into the corn 200 yards down the fence. They were far from matching the deer I wanted, but they were good whitetails and I yielded to temptation. As soon as they were out of sight in the corn, I climbed down and started after them. I was pussyfooting down a corn row 70 yards from the tree when something made me look back. Mossy Horns was standing under my platform looking hard in my direction. Apparently, he wasn’t sure what I was, but he walked slowly away until he got my scent, and that was that.

About a week later, Charley Marlowe was in a tree blind when four deer walked past him at good range. He drove an arrow into a young buck, and it ran out into the corn and dropped. Before Charley could climb down, the big deer stepped out of the brush 30 yards away, stood broadside, blew a couple of times, and ran back toward the river. Marlowe’s license was filled, but he admitted afterward he was glad when the deer skedaddled.

“A man can stand just so much temptation,” he told us with a dry grin.

Before that season ended, I had another chance. I was back at my stand in the cottonwood, and my wife Velma, who has bowhunted as long as I have, was in a smaller tree about 50 yards away. We waited all afternoon, and dusk was deepening when I started to climb down. Just then I heard a twig break, and there was the big buck, head lifted, ears pointed ahead, taking short mincing steps. I had never seen an animal more alert.

I FROZE and let him walk under my tree and beyond it. Then I drove my arrow at his shoulder. I heard it hit, a good solid thunk, and he flinched and bolted. There was a woven-wire fence nailed to the tree Velma was in, and he crashed into it so hard he almost toppled her off her platform. Then he was gone.

We could find no blood, and by then the light was so poor we decided to go up to Dan’s house, kill half an hour over a cup of coffee, and come back with a flashlight. That was as long a 30 minutes as I can remember.

We found the feathered end of my arrow not far from where the deer had crashed into the fence, but that was all we found. There was no blood or any other hint of what had happened. I was haunted the rest of that season by worry that I might have killed him—that he might have crawled into a thicket to die without our ever finding his magnificent rack. The last week I filled my license with a 160-pound, three-point (Western count) buck, my third deer and the first with a bow.

Nothing happened the next summer to relieve my fears that I had killed Mossy Horns. For the first summer in three years Dan failed to see him, and we resigned ourselves to the likelihood that if my arrow had not finished him, time had. From the size of his rack when I first saw him in 1958, we concluded he’d be at least eight years old.

The next season didn’t have quite its usual appeal for me, and as it went along and my luck stayed bad, I felt less and less enthusiasm. Charley and Del each killed a nice doe—Del’s first deer—and my wife got a four-pointer. Gene was laid up temporarily from a heart attack. I kept on hunting alone, but my heart wasn’t in it.

The season was three quarters over and snow was piled in deep drifts on the bottoms before I got a chance at a deer. Late on a bitterly cold afternoon, I was back in the same tree where I had shot at the big buck when I spotted a button buck coming through the willows 100 yards away. Then a bigger one walked into sight behind him, and bringing up the rear was the deer I had given up seeing again.

My heart did a somersault. He was walking warily and craftily, turning his head from side to side to work that enormous rack quietly through the brush. It looked no different from when I had seen it last, except that it seemed bigger. The tangle of stubby points stood out like overgrown thumbs, and the down-curving prongs on either side of his head were at least a foot long. In spite of the icy wind, I started to sweat.

The two lead bucks turned out toward the corn, but the big fellow stayed in the willows. Halfway between the brush and the field, the smaller bucks tried to get through a deep snowbank but couldn’t, and they finally turned away from me to go around it. Now the big deer followed. It was as if he remembered that cottonwood of mine and was avoiding it.

While the three were picking their way through a clump of trees at the far end of the cornfield, half a dozen does came out of the willows single file, walked under my platform within six yards of me, and started to feed. The two smaller bucks came down along the edge of the field and joined them, but Mossy Horns hung back in the timber. It was almost dark before he ventured into the corn, and then he stayed well out of range.

That was the only time during the 1961 season that any hunter laid eyes on him, but at least we knew he was still in the area. I gave him up finally, and filled with a four-pointer.

Dan had a field of milo that he didn’t get around to harvesting that fall. A herd of whitetails fed there all winter, the big buck among them, and early in the spring, on the bottoms not far from that field, Dan had the rare luck to find his shed antlers lying close together. Next to the head itself, that was about as good a trophy as a man could ask for. The tips of several points were missing, but one down tine measured 11 inches, the other 13 (one still carried a ring of dried velvet), and the rack was the most impressive any of us had ever seen. I had proof now of every claim I had made about this deer for four years.

The story of that find has an interesting sequel. Last spring, some six months after Mossy Horns was finally killed, we learned that Max Wilkie, a farmer living about two miles from Dan, had found another set of shed antlers from this same buck four or five years before. The down-swept tine on the left side is broken off about three inches from the main beam on this set, and the right one is short, but from the shape and points there is no question that the rack belonged to a younger Mossy Horns.

In the summer of 1962, I decided that if I couldn’t get to the big buck, I’d try bringing him to me. I spent weeks cutting deer trails through the heavy brush of the bottoms, in places where I had seen him most often, and building tree blinds overlooking them. Then, a month before the open season, I cleared out to give him and the other whitetails a chance to get used to them.

Two other partners joined us that fall, Kenny Whitesel, a farmer living near Hastings and one of Nebraska’s top bowhunters, and Charley Marlowe’s 16-year-old son Chad. That made six in the party, and each of us had his heart set on Mossy Horns. I was beginning to worry on one score. Would his head still be the trophy it had been in the past? Unless we were wrong, he was not less than nine now, and bucks carry poor racks in their declining years.

I got the answer to my doubts before the season was many weeks old. A new interstate highway, I-80, was being built through our hunting grounds on the north side of the Platte, and the north channel had been temporarily dammed. Walking the dry river bed one afternoon, I saw unmistakable tracks where the big buck had gone up the bank into an alfalfa field. I tracked him to a willow-grown island, jumped him, and got a good look at his antlers as he crashed away. They looked as big as ever.

I avoided that island from then on, not wanting to drive him out of his bedding area, and I also shunned the trails he was using. I saw him twice the next week. The first evening I was in a tree where a runway crossed a big slough. Just before dusk, four or five does walked under the tree, and then a four-point buck followed, stopping beneath me to rub his antlers on a bush. The big deer showed up right after that, but he moved off without coming close enough for a shot. The next time he was even more cautious, sneaking out to the edge of the brush downwind from me and then vanishing quietly.

SEEING NO MORE of him for a week, I searched the river bed again, found his tracks on a trail he had not used before, and built a new blind. I had a hunch it was now or never. Bowhunting season would close November 2 for nine days while riflemen took the field. Mossy Horns had grown to a legend in that neighborhood now. A lot of hunters wanted him, and I doubted he’d survive the gun season.

An hour before dark, my first evening in the new blind, I saw him slip out of thick willows on an island and head my way. He crossed the dry channel, entered the brush below the bank on my side, and came on until he was only 15 yards from me. I had deer scent sprinkled around the base of the tree, the wind was in my favor, and I was sure it was all over but the shooting.

The deer had other ideas. He stopped in brush so thick I could barely make out his outline. Nothing that has happened to me in a lifetime of hunting shook me up the way the next 10 minutes did. They seemed like 10 hours. Neither of us moved a muscle. Although a deer is not likely to look up of his own accord, he is almost sure to detect the slightest motion, even in a tree overhead. Finally the buck turned, bounded up on top of the bank, still in thickets where no arrow could get through, and started to walk around my tree. The wind had died, and everything was so quiet I was afraid he’d hear my pounding heart.

He halted where a fence came down to the river, not 20 feet from my platform, and I wanted to try for him the way a strangling man wants air, but I knew better. If I muffed this chance, I couldn’t hope for another.

He tortured me for another 10 minutes, finally clearing the fence and walking out into a field of alfalfa. He was 45 yards from me when he stepped out of the brush, and I sent my arrow at him instantly. It sang just over his back and whacked into the ground beyond him. He was back in the thicket in one long jump.

WE WERE HUNTING every possible minute now, knowing the bow season would soon recess. On the last afternoon in October, Halloran, Whitesel, and I got to Dan’s place early, hurried to the bottoms, and chose our stands. Del Austin and Charley Marlowe left Hastings after work, knowing they’d have less than an hour to hunt but counting that worth the trip.

Del had planned to use one of my blinds but couldn’t afford to waste time looking for it. So he put up a small, portable platform he’d brought, a rig that could quickly be hung in a tree. Before he climbed up on it, he poured buck lure around the tree and trimmed away some willow tops that might interfere with his shooting.

There was only room to stand on the platform, and Del hadn’t hung it quite level. His legs ached and he couldn’t change position, but he stuck it out as long as there was enough light for shooting. At last he gave up, clipped his arrow back in the bow quiver and took out a cigarette before climbing down.

As he opened his lighter, he heard a crashing 50 yards upwind, and then the biggest deer he’d ever seen broke out of thick brush. In the fading light, Del could not see the horns clearly enough to identify the buck, but he realized that this was a buster whitetail and that its guard was down, maybe because of the deer scent around the tree. That can be a powerful attraction for a buck at the peak of the rut.

The deer came at a dead run, stopping once and half turning as if looking for something, then coming again. He skidded to a stop, broadside, 20 yards from the tree, and Del drove a broadhead in behind his front leg. The buck whirled, plowed into the brush, and was gone. Del heard him stop briefly 40 yards away, and then walk on through the dry leaves.

Marlowe, Halloran, Whitesel, and I got back to Dan’s about dark. We waited an hour, then started out with flashlights to look for Del. We met him halfway to the river, listened to his story, and went back with him to search for the deer. He was still not sure it was Mossy Horns, but from his description I had very little doubt.

We found the trail easily. There was a lot of blood, and before we had followed it far we found the broken arrow, snapped off 10 inches above the head. That meant a hard hit with deep penetration. We trailed the deer through brush and slough grass for three hours, and by then our lights were giving out and the blood sign was down to a few drops or a smear every 30 to 40 yards. At last we lost it altogether. Del tied his handkerchief on a bush to mark the place, and we went home to wait for morning.

I DIDN’T SLEEP MUCH, and at daylight I was back. I picked up the trail and had followed it another 100 yards when I heard Del and Dan coming. We spread out, and the next time I saw Del he was crouched down with his bow at full draw. But after a few seconds he eased off and motioned for me to circle in from the other side. Then I saw the deer lying in a clump of willows, antlers tangled in the brush. One look was all I needed. Del had killed the buck I had hunted for the past five years.

The signs of age were plain on him. He was gray around the face, his loins were sunken, and he carried hardly an ounce of fat. From what I know of meat animals, I estimated he was 60 pounds lighter than he’d been in his prime two or three years before, but still he dressed out at 240. His rack was less massive than the shed one Dan had found, but it was still a terrific trophy. He was as stout-hearted as ever, too. Del’s arrow had done a clean and thorough job, yet he had run nearly a quarter of a mile after he was hit.

Measured by Glenn St. Charles of Seattle, an official measurer for the Pope and Young and Boone and Crockett clubs, his rack scored 279-7/8 points. The Pope and Young Club is concerned with recording trophy game shot by bowmen, and this deer’s antlers exceed its existing record of 186-2/8 for a non-typical whitetail by nearly 100 points. Even more impressive than that, his rack is the third biggest recorded for a nontypical whitetail and the biggest ever claimed by a hunter. The two top heads in this category score 286 and 284-3/8. But the late Grancel Fitz, writing in the most recent edition of Records of North American Big Game, published by the Boone and Crockett Club in 1958, said of them: “In the nontypical whitetail class we know nothing of the two very old and strikingly similar specimens which stand at the top, except that they are Texas bucks from the old-time Buckhorn Saloon collection in San Antonio … But both of these remarkably symmetrical freaks are far ahead of any other trophies in their class.” And certainly Mossy Horns was way ahead of the next buck on the nontypical whitetail list, shot in British Columbia in 1905 and scoring 245-7/8.

We could find no sign of my shot of two falls before, even when we dressed him, and the only guess we could make was that my arrow had struck one of the down-pointing tines alongside the buck’s neck and broken its head off without drawing blood.

We dragged him across the bottoms to the edge of the fields, and I stayed with him while Del and Dan went back after Del’s car. I had a lot to think about all the miles I had tracked him, the many times I had seen him, the shots I’d had and missed. Until the previous night, I had always kidded myself that I’d be the hunter to down him. I suppose because I had hunted him longer than anyone else and thought I had earned the right. I won’t say I wasn’t jealous of Del’s good luck, for I’m afraid I was. But at the same time, next to taking that tremendous rack myself, nothing could have pleased me more than having it fall to a hunting partner, a fellow bowhunter, and a sportsman who deserved it on every count.

Turning that angle over in my mind, I felt better. And then I had another happy thought. The big buck had left plenty of sons there on the Platte bottoms. Some of them were bound to turn out big, and somewhere among them there might even be a nontypical rack something like his.

Read more OL+ stories.