This story, “Ghosts by Night,” appeared in the December 1952 issue of Outdoor Life. It is still legal to hunt rabbits at night in Indiana during most of the season.

It was the last week in December. The lakes in northern Indiana were freshly frozen, and big bluegills were schooled up and biting like blackflies under the new ice.

I live in the kind of place a man ought to live in, a hundred feet from the edge of a medium-size lake that provides bass, crappies, and some of the best bluegill fishing I’ve ever found anywhere. I have a small duck pond and two rabbit swales in the first field behind my house. I wouldn’t trade palaces with a king!

On this particular occasion it happened that half the bluegill population of the lake had gathered in a small bay in front of my place. There was a spot out beyond my boat dock, no more than a city block offshore, where a goldenrod grub or a corn borer lowered through a hole in the ice into the dark water at the end of a nylon line was as sure to get results as a saucer of cream set in front of a hungry cat.

The winter wind was cold but my wife and I had worked out a system that permitted us to do our ice fishing without undue discomfort.

We’d build a roaring fire in our fireplace and set a pot of coffee on the back of the stove and a plate of sandwiches on the table. We’d spend an hour or two on the lake, then retreat to the house, sit near the fire, and have coffee and sandwiches. Thus fortified, we’d be ready for another bluegill session. Two sorties onto the ice provided all the fish we wanted.

On this particular day we’d spent the afternoon in just that way. After supper I went out into the backyard to clean the pailful of fat, firm fish. Summer or winter, I like elbowroom for that job, and a brilliant moon gave plenty of light. A couple of days earlier we’d had a new fall of snow, making fields and hills and the orchard look like a Christmas card. The lake was a white plain with patches of dark timber on the far shore. A million diamonds sparkled on the snow, and the gnarled apple trees threw graceful patterns of blue-black shadow.

Down in the garden, dead cornstalks made a pleasant rattling sound in the cold wind, for all the world like the dry rushes of a duck blind rustling in the darkness of an overcast November morning.

When I walked down past the garden to discard the fish heads a cottontail rabbit took sudden flight along the edge of the corn patch. He fled across the orchard like a gray ghost; his shadow, floating beside him, was darker than the rabbit himself.

I watched him disappear and suddenly I wanted to sample again a special kind of sport I hadn’t tried since I was a kid, thirty years before.

I took the pan of bluegills into the house and left ’em in the kitchen sink for my wife to wash and put away. I slipped into a quilted jacket, dumped half a box of shells into the pockets, got my 16 gauge double-gun out of the closet, and walked across the fields to Ed Graham’s house. He’s my nearest neighbor, and a kindred spirit.

He came to the door in answer to my knock, and his face lighted up when he saw me standing there. Then he noticed the shotgun and his jaw sagged. “What in heck are you up to?” he demanded.

“I’m going rabbit hunting,” I said. “And so are you.”

“Tonight?” Ed sputtered. “Now, look!”

“A cottontail hunt,” I insisted, “and I’m not kidding. Didn’t you ever hunt rabbits by moonlight?”

“No, and I don’t believe it’s legal,” Ed replied.

“It’s quite legal — in this state at least — so long as you don’t use an artificial light. You can hunt ’em any hour of the day or night, but you can’t shine ’em,” I explained.

“Sounds crazy to me,” Ed declared.

“It is, a little,” I admitted. “You don’t shoot at the rabbit. You shoot at his shadow on the snow. It shows up plainer than he does. But crazy or not, it’s fun. I did it when I was a kid, and sometimes killed as many as a rabbit in a night, too. You coming or not?”

Ed started to argue, then decided not to. “Sure I’m coming,” he said, and then went to get his boots and stuff.

“We want the dog?” he asked when he rejoined me. He keeps a beagle that’s as good on rabbits as any hound I’ve ever known.

“No dog. Not tonight. Any rabbits we get we’ll have to sneak up on, and they’ll move fast enough without hound music to hurry ’em along.”

We swung across the fields toward a patch of woods where a dozen cottontails usually hang out all winter long. The crisp dry snow crunched underfoot. Save for that the night was perfect for what we had in mind. The big round moon was high overhead now, and brush, weeds, and fences loomed black against the white snow.

“This is sure new to me,” Ed remarked, “and somehow I don’t take much stock in it. Just how do you propose to find the rabbits?”

“Walk slow and careful where they’re likely to be, until you see one.”

“Yeah, and then what?”

“Shoot him. Or shoot at him.”

“You mean you shoot ’em sitting still?” Ed grunted. “Don’t give ‘em any warning?”

“That’s right,” I assured him. “And don’t start feeling sorry for them until you’ve shot a couple!”

We came into the woodlot, and across a clearing in front of us I saw a patch of shadow hunched on the ground, close to the bigger shadow cast by a tree. I halted and studied it carefully, pulling Ed to a stop beside me.

The shadow was too long for a rabbit. Yet somehow it looked rabbitlike. I even imagined I could see the vague, distorted outline of cottontail ears at one end of it.

“Whadda you see?” Ed demanded.

“Not sure,” I whispered, “but I think maybe I see a rabbit.”

“You mean that shadow near the tree there?” I nodded.

“That’s a rock,” Ed said loftily. “That’s too big for a rabbit.”

We moved ahead again and as our first steps crunched in the snow, Ed’s “rock” broke into two separate shadows that fled pellmell in different directions. Two rabbits had been sitting there, close together, watching us warily as we walked down through the woods.

I threw my gun up and blasted one barrel after the other at the shadow that was running to the left. It only put on speed. Ed’s 12 gauge pump sent three heavy crashes thundering through the stillness of the winter night, and I looked off to the right in time to see his rabbit top a low ridge and disappear.

“Well, I’m beat,” he muttered. “I didn’t believe that was a rabbit, let alone two of ’em. We should have got ’em both.

“Say, you’re right about all this,” he added, chuckling. “From now on I’m shooting at anything that throws a shadow, provided it’s smaller than a tree. And I won’t wait for it to move, either.”

We went on around the swale, and in an open thorn-apple thicket at its lower end he grabbed my arm. “Look!” he whispered. “There’s one.”

The patch of shadow lay on the snow at the edge of a thorn clump thirty yards ahead. It was rabbit size, all right, but the shape didn’t look quite right to me. Before I had time to voice my opinion, however, Ed’s pump gun was up. He had trouble lining it on the shadow. The gun wobbled and weaved while I could have counted five. Then it stabbed a finger of red fire from the muzzle, and the blast shook the crisp moonlight night.

The shadow stayed exactly where it was, changing neither shape nor position. Ed had made a mistake.

He knew it, too. He lowered the gun slowly and waited for something to happen. When nothing did, we walked over for a look. The shadow belonged to a small stump that protruded a few inches above the snow.

Ed and I separated after that and took opposite banks of a brush-grown ditch. We had traveled half its length, and I was walking as catlike as I could on the crisp snow, when I saw a rabbit move at the margin of a willow clump. While I watched, it moved again, one short hop down the slope.

But when I shouldered the gun I was up against a problem. Against the white snow of the field I could see enough to point. But against the brush and weeds I couldn’t even distinguish the outline of the gun.

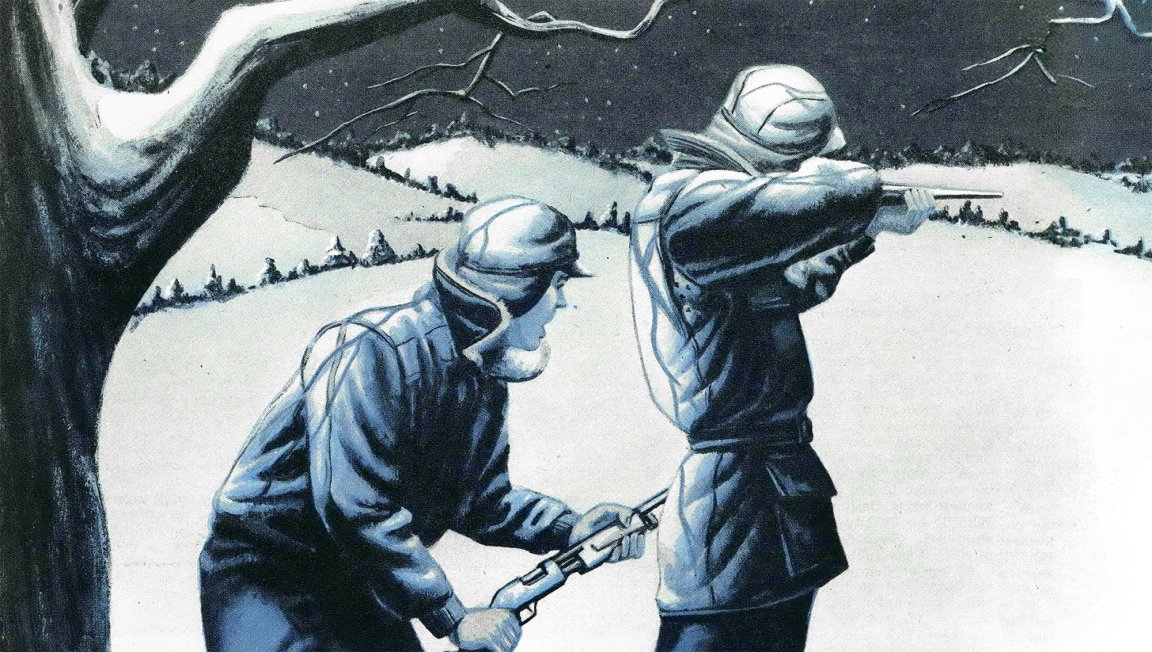

Illustrated by Frank McQuade / Outdoor Life

Finally I took a cautious step to the right, caught a glint of reflected moonlight along the barrels, laid them on the dark shadow of the rabbit, and cut loose.

Snow flew all around the cottontail but he didn’t run or fall over, and I knew I had been tricked as badly as Ed. I walked up sheepishly to see what had fooled me and found a clump of dead milkweed lifting above the snowy ditch bank. Swaying back and forth on its slender stem in the light wind, with an upthrust dry pod to imitate a rabbit’s ear, its deception had been perfect.

“Get him?” Ed called.

“I sure did,” I yelled back. “But he’s got brown seeds in his ears!”

That brought Ed to my side of the ditch, where I pointed silently to the milkweed clump.

“Shucks,” he jeered, “you’re no smarter than I am.”

Beyond the next field we came into an abandoned orchard on the slope of a long ridge.

“There’ll be frozen apples under these old trees,” I pointed out. “And there’s nothing a rabbit likes better at this time of year.”

Ed took the ridgetop, while I followed the foot. If anything moved between us we’d both have a chance at it.

I went along at a slow walk, stopping in the shadow of each tree to scan the space ahead, the slope of the hill, and the strip of snow that lay between me and the rail fence at the foot of the orchard.

I had halted under the third tree when I saw something move down by the fence, and the next second a rabbit streaked uphill in front of me.

Actually he was no more than a ghostly blur moving over the snow, but his shadow fled beside him, blue-black and plain to see.

I swung the gun up and tried to get the moon glint I needed on the barrels, but the angle was all wrong. The rabbit showed no sign of slowing down and I realized I’d have to try snapshooting.

I fired the right barrel, and the fleeing shadow put on speed. The left barrel sent a cloud of snow flying beyond him, and I shouted a warning to Ed as the shadow disappeared over the crest.

A second or two later Ed’s 12 gauge smashed out its heavy report. “I got him,” he yelped.

When I walked up to him, he was as proud and pleased as a kid with his first cottontail.

“Know what happened?” he burbled. “He was moving along like he had a rocket in his tail, and I couldn’t even see the gun barrel. Then all of a sudden he stopped and sat up to look around, and the moon hit me just right. I could even see the brass bead. It was like knocking over a duck in a gallery.”

I wasn’t surprised to spot a hunched, rabbity shadow at the edge of the brush. I waited for it to move but I didn’t dare wait too long; one hop would take it into shelter. I counted ten and shot.

At the end of the orchard, Ed shot again, but there was no triumphant announcement that time.

“I matched your milkweed stunt,” he admitted when I caught up with him. “Only mine turned out to be goldenrod. It beats the devil how a weed can look like a rabbit when the wind moves it just right!”

We came to a small swale where wild grapevines made a dense tangle. A cottontail delights in having that kind of cover close by while he frolics under a winter moon. I wasn’t surprised to spot a hunched, rabbity shadow at the edge of the brush. I waited for it to move but I didn’t dare wait too long; one hop would take it into shelter. I counted ten and shot. The shadow didn’t move, and for good reason: it was cast by a small rock that lay bare of snow. I didn’t even have the excuse of seeing “ears,” and could find no retort to Ed’s razzing.

We followed a brush-bordered country road back to his house. With only five minutes between us and the coffeepot we knew his wife would have waiting, we dipped down into a willow swamp that swarms with rabbits in midwinter. They move into such places for food and cover when the snow comes.

Ed turned to skirt the swamp. I kept to the road. Halfway through, walking slowly and noiselessly on the hardpacked snow, I saw a shadow come out of the willows forty yards ahead.

Read Next: The Best Guns for Rabbit Hunting

It paused briefly in the middle of the road, then pivoted and loped straight away from me, and I had the chance I’d been waiting for.

The moon was in my favor at last. It shone square on the gun barrels as I swung them up, and I knocked the rabbit kicking.

Ed and I met at the far side of the swamp and counted up the score.

“One stump, one rock, two clumps of weeds, and two rabbits,” he announced. “Not bad for amateurs. I still think a man has to be crazy to like it, but if that’s true I’m a long ways from sane. Let’s go home and drink that coffee, and if it’s clear tomorrow night we’ll give this another whirl!”