This story, “Seagoing Buck,” first appeared in the August 1955 issue of Outdoor Life.

I’VE HAD MY SHARE of frustrations in deer hunting, but only once have I had to fight off an enormous shark that was I trying to kill the same buck I was after.

Though deer and sharks don’t usually rub shoulders, I run a hunting-fishing lodge on Chester Bay, in Nova Scotia, where there’s a wild forest on one side and salt water on the other. The 40 miles of wilderness inshore from the highway that runs past my camp is a mixture of forest, bogs, barrens, lakes, and streams—a tight, tough country where it’s hard to get in range of game before it sees or hears you. Because I’m given to impatience, I’m always looking for easier ways of getting my deer than trying to still-hunt with the stealth of a panther.

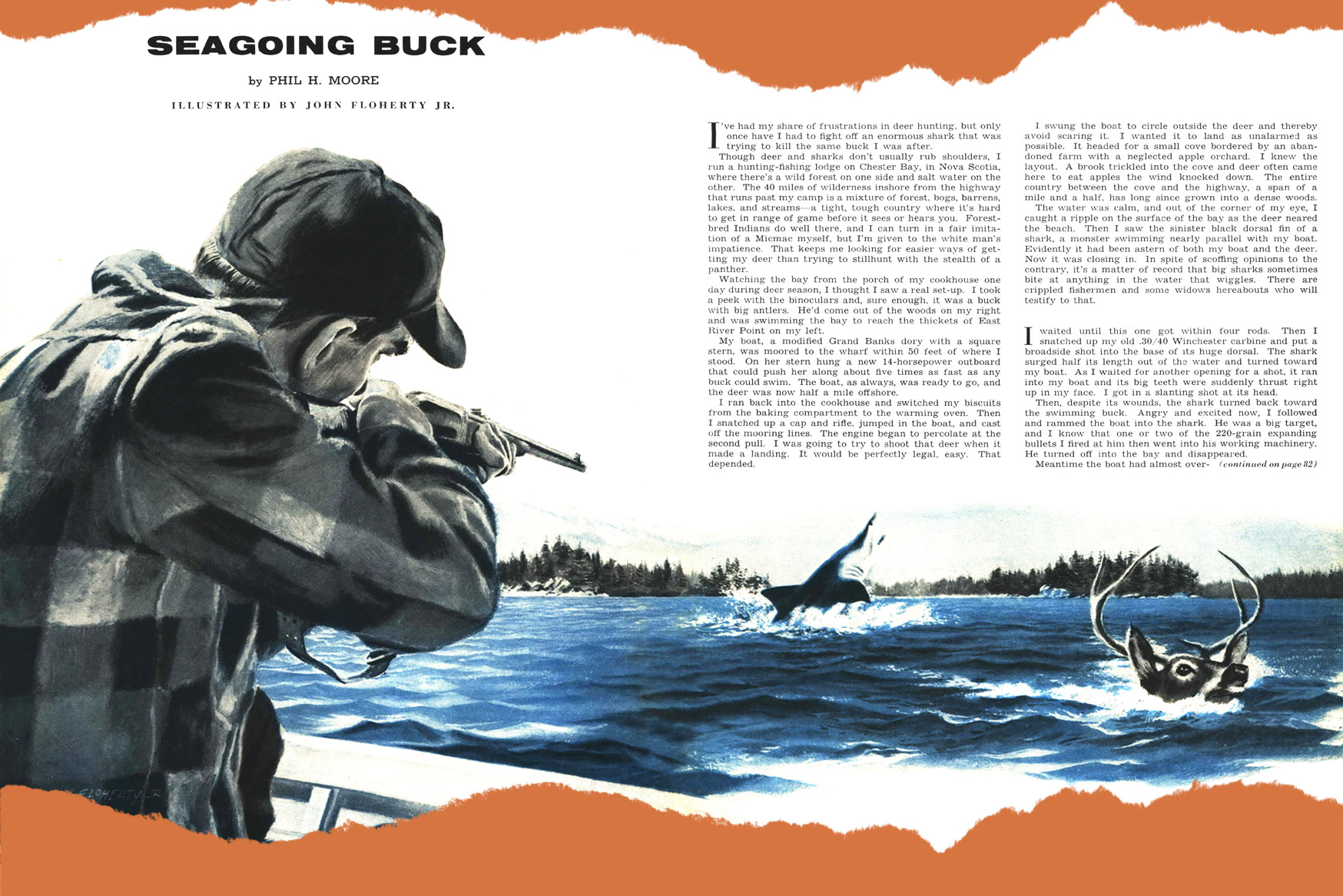

Watching the bay from the porch of my cookhouse one day during deer season, I thought I saw a real set-up. I took a peek with the binoculars and, sure enough, it was a buck with big antlers. He’d come out of the woods on my right and was swimming the bay to reach the thickets of East River Point on my left.

My boat, a modified Grand Banks dory with a square stern, was moored to the wharf within 50 feet of where I stood. On her stern hung a new 14-horsepower outboard that could push her along about five times as fast as any buck could swim. The boat, as always, was ready to go, and the deer was now half a mile offshore.

I ran back into the cookhouse and switched my biscuits from the baking compartment to the warming oven. Then I snatched up a cap and rifle, jumped in the boat, and cast off the mooring lines. The engine began to percolate at the second pull. I was going to try to shoot that deer when it made a landing. It would be perfectly legal. Easy? That depended.

I swung the boat to circle outside the deer and thereby avoid scaring it. I wanted it to land as unalarmed as possible. It headed for a small cove bordered by an abandoned farm with a neglected apple orchard. I knew the layout. A brook trickled into the cove and deer often came here to eat apples the wind knocked down. The entire country between the cove and the highway, a span of a mile and a half, has long since grown into a dense woods.

The water was calm, and out of the corner of my eye, I caught a ripple on the surface of the bay as the deer neared the beach. Then I saw the sinister black dorsal fin of a shark, a monster swimming nearly parallel with my boat. Evidently it had been astern of both my boat and the deer. Now it was closing in. In spite of scoffing opinions to the contrary, it’s a matter of record that big sharks sometimes bite at anything in the water that wiggles. There are crippled fishermen and some widows hereabouts who will testify to that.

I WAITED until this one got within four rods. Then I I snatched up my old .30/40 Winchester carbine and put a broadside shot into the base of its huge dorsal. The shark surged half its length out of the water and turned toward my boat. As I waited for another opening for a shot, it ran into my boat and its big teeth were suddenly thrust right up in my face. I got in a slanting shot at its head.

Then, despite its wounds, the shark turned back toward the swimming buck. Angry and excited now, I followed and rammed the boat into the shark. He was a big target, and I know that one or two of the 220-grain expanding bullets I fired at him then went into his working machinery. He turned off into the bay and disappeared.

Meantime the boat had almost overrun the buck, which was now making for the shallows in a panic. It hit the beach a couple of boat lengths ahead of me, and my teetering shots from the boat missed. I backed the stranded boat off and went home, planning to come back next day with some apples.

Vince Hume, one of my guides, was with me when I returned to scatter a new supply of apples under the old trees. He helped me fix up a watching place, too, but we both knew it was no use to hang around for the time being. A smart old-timer like this seagoing buck would have long since learned not to feed under apple trees during daylight hours. Vince thought I was wasting time anyway, trying to bait the buck in such an obvious manner.

“Tomorrow we’ll bring more apples,” I told him.

He just laughed and shrugged. It meant another easy day for him.

Each day for six days we found our apples gone. Tracks of several deer were about the place, and a big buck’s was always among them. Each day we replenished the apples, cut wood for a lunch fire, and talked and laughed over our outdoor meal I wanted any game within hearing to become familiar with our clatter and chatter so they’d decide it meant no danger to them.

On the seventh day after my first experience with the big buck the wind came offshore from the north. The day was dark and cloudy. I told Vince to step the mast in the dory so we could sail across and land silently. The way the wind was blowing, we could make a long reach to just off the mouth of the cove, then unstep the mast and paddle—not row—the boat to the beach against the wind. I wanted to avoid the creak of oarlocks, and we’d be in a lee where paddling into the wind would be fairly easy.

Once we’d beached the boat, I told Vince to circle quietly, first toward the west until he could see the shoreline on that side of the peninsula, then north for half a mile, then east for a mile, and finally back south to the boat. I figured that buck and the other deer were living in cover close to the apples. If Vince got upwind from them they’d move down toward the shore where I could see them.

Vince listened to my directions and grinned with quick understanding. “I getcher, boss,” he said, “but do I shoot whatever I see?”

“You have a license and a gun. It’s up to you. I’ll take what’s left.”

VINCE MELTED into the trees like a dawn mist. I began to secure the boat—a long line ashore with a grapple hook on it and a stern anchor against a rising tide. Though I expected no immediate result from Vince’s drive, I didn’t intend to have the safety of the boat on my mind after I’d hidden my self in a blind. It would probably be a long wait.

I’d just stretched out the anchor line from the bow and picked up my rifle from the thwart when I heard something that sounded like a snort. Then a crash. Over my left shoulder I saw a deer bounding right toward me and the dory!

While I stood with a wet line in one hand and the gun in the other, the deer, evidently in a blind panic, bounced straight at the boat and hit the water alongside. Spray flew all over me.

Then the animal saw me. It whirled with another great splashing of water and ran like a wet streak for the woods. I managed to fire one shot when the animal was still only a few yards away. I missed.

For some hours I sat brooding in the little blind near the beach. Two does minced out and looked my way. They were legal game, but I wanted no pretty little pets. Finally Vince put in an appearance.

“Was that your buck that nearly ran over me when I first started in? I heard you shoot. Where’s the deer?” he asked, all in one breath.

I nodded and pointed to the woods. It was the bay-swimming buck, and he was back in the sheltering bush, safe and sound.

“What happened here on the beach?” Vince was looking at the gashes in the sand. “Did the buck try to jump in the boat?”

I told him it did.

“Did you see those two does?” he asked.

“Yep. But I want that buck. And you made a dandy drive. Those two does drifted out as though hardly annoyed by the man behind them. But what stampeded the buck, Vince? I’ve often told you—”

“Yeah, I know. Just drift ’em along. Don’t panic ’em. But that beast was on a dead run for the cove—practically brushed by me—before I’d been in the timber 10 minutes. Something to windward must have scared it.”

Vince talked with a straight face. I could take it or leave it, but I still believe he jumped that buck just for the fun of seeing it run. But I’d never know, so I let the matter drop.

“We’ll go home now,” I decided, “but the next suitable day I’ll go through this land and find that buck.”

“By now that buck’s five miles from here,” grinned Vince.

“Wait and see,” I said.

DURING THE NEXT three days I took time out to run the dory over to the cove with more apples. I told nobody what I was up to, especially not Vince, who was busy guiding sportsmen. I was waiting for a real dirty day, a wet or snowy one, for the system I intended to try on my seagoing buck. I wanted it soft and wet underfoot and so stormy few hunters would care to go out.

I heard the wind moaning out of the northeast long before daylight on the fourth day. This was the day. I got the wife of one of the guides to take charge of the cook stove, which had become one of my chores during the deer-season rush, and set off. This time I took the highway around to the head of the peninsula and slipped down the western shoreline. When I was within a quarter of a mile of the old orchard I began a slow, careful stalk along the lee side of the timber. As I zigzagged toward the east I crossed a big buck’s track twice. Once he was heading north on the jump, later going south in a slow walk. Other deer tracks were about. I sneaked up on a small buck just for the fun of it. The bushes were wet and pliable and the light snow was slushy. My feet made no noise, and my soft wool clothes made no alarming swishes on the brush. I got close enough to have touched the young buck with a boat hook. Then I stood perfectly still. It finally snorted and trotted away, more puzzled than frightened.

I had the wind of the beasts I hoped to see. I’d soft-footed a scant 100 yards when I spied a patch of gray and white in the underbrush. It might be a deer. Yet no head was visible. I had to be sure.

As I stood there looking at my compass (one can easily go astray while concentrating on game) I heard several coughs from the direction the little buck had taken. Then I heard a loud crash and clatter of horns. Apparently the small buck had blundered onto another male, one which most likely was accompanied by a doe or two. That could be my big buck. The rut had begun and the larger bucks take the first pick.

Now a strong buck scent reached my nostrils. To most people, the smell of a buck during the rutting season is like musty, decaying leaves. But since the forest floor smells about the same way, especially when a man lifts a foot from a wet and muddy hole, it’s difficult for an amateur to identify the buck scent.

All this ran through my mind as I began to stalk this fresh quarry. If it was my seagoing buck, I’d instantly recognize him. A buck’s antlers are as distinctive as a man’s face, and I’d noted every detail of the big boy’s horns as he swam the bay that first day.

I had the wind of the beasts I hoped to see. I’d soft-footed a scant 100 yards when I spied a patch of gray and white in the underbrush. It might be a deer. Yet no head was visible. I had to be sure.

There was a movement to the right—another patch, brownish in color. It moved again. That might be another deer, or it might be a man. I didn’t dare shoot until I saw enough of the target to be sure. Then I made out the legs of a deer, but were they holding up that fine head of antlers I wanted?

My eyes darted from left to right and back again. The carbine was raised to my shoulder. The front sight rested first on one brownish spot, then another, but I still couldn’t see the target. My shoulder and arm were tiring. The front sight was making little shaky circles.

The deer seemed to be feeding.

Just ahead of me was noisy ground hemlock. I couldn’t move closer, nor circle, without losing sight of the deer. The strain of sighting the gun became intolerable. I simply had to lower the piece. As I did, the butt of the carbine clicked against the hilt of my belt knife.

All three brown patches came to life. The center beast whirled toward me for a look—a doe—but on the left a big spray of antlers poked up through the bushes. The carbine slowly lifted, then swung until the front bead rested on the big neck. I squeezed the trigger.

The buck jumped directly toward me. I fired again and he pitched forward, thrashed a few seconds, and lay still. The second shot had gone through the forehead just beneath the horns.

It was my seagoing buck, sure enough.

I glanced at my watch. There were two hours to dark. The northeast wind was rising and rain and snow drove through the timber. As I gutted the big animal and punched off its hide, I decided to take out one hindquarter and let Vince pack in the rest next day.

I MARKED the spot of the kill and headed north to the highway, using my compass to set a course that Vince could follow back with his compass. Since we dislike marking up the timber on other people’s land with big blazes, I cut a few long, narrow marks as I went, blazes that would bark over in one season. I hit the highway at dark.

Next day Vince found the place where I’d hung a large, spreading spruce limb on a white birch, a thing quickly noticed by a woodsman. Beneath it lay the dressed buck. Vince brought in the remaining venison, but he left the antlers and hide for me to bring out—he said. He was away at guiding again before I could persuade myself to send him back for them.

I figured the kill had been nearer the water than to the highway, so the following day I took the dory to the cove. I wanted these antlers and the hide. To find the kill in a thick woods from this new angle, I marked on my map the compass course I followed to the highway on the first trip out. Then on the map I extended the line from the highway through the kill spot and straight to the coast. The line struck the water about a quarter of a mile east of the apple-tree cove. I started there and walked the compass course north until I came to the kill. Then I picked up the antlers and the beautiful hide and compassed back south to my boat.

As I pushed off the dory and hoisted the sail, I allowed myself a grin of satisfaction. I was thinking that, on sea or land, a compass is a very handy instrument. Yes, a lot of things go into the getting of a trophy buck. This one even required a knowledge of how to deal with sharks.

This text has been minimally edited to meet contemporary standards.

Read more stories from the Outdoor Life archives:

- A Classic Stalk for Yukon Caribou, From the Archives

- A Desert Deer Hunt Gone Wrong, From the Archives

- The Coolest Old Jack O’Connor Photos From the Outdoor Life Archives

Or read more OL+ stories.