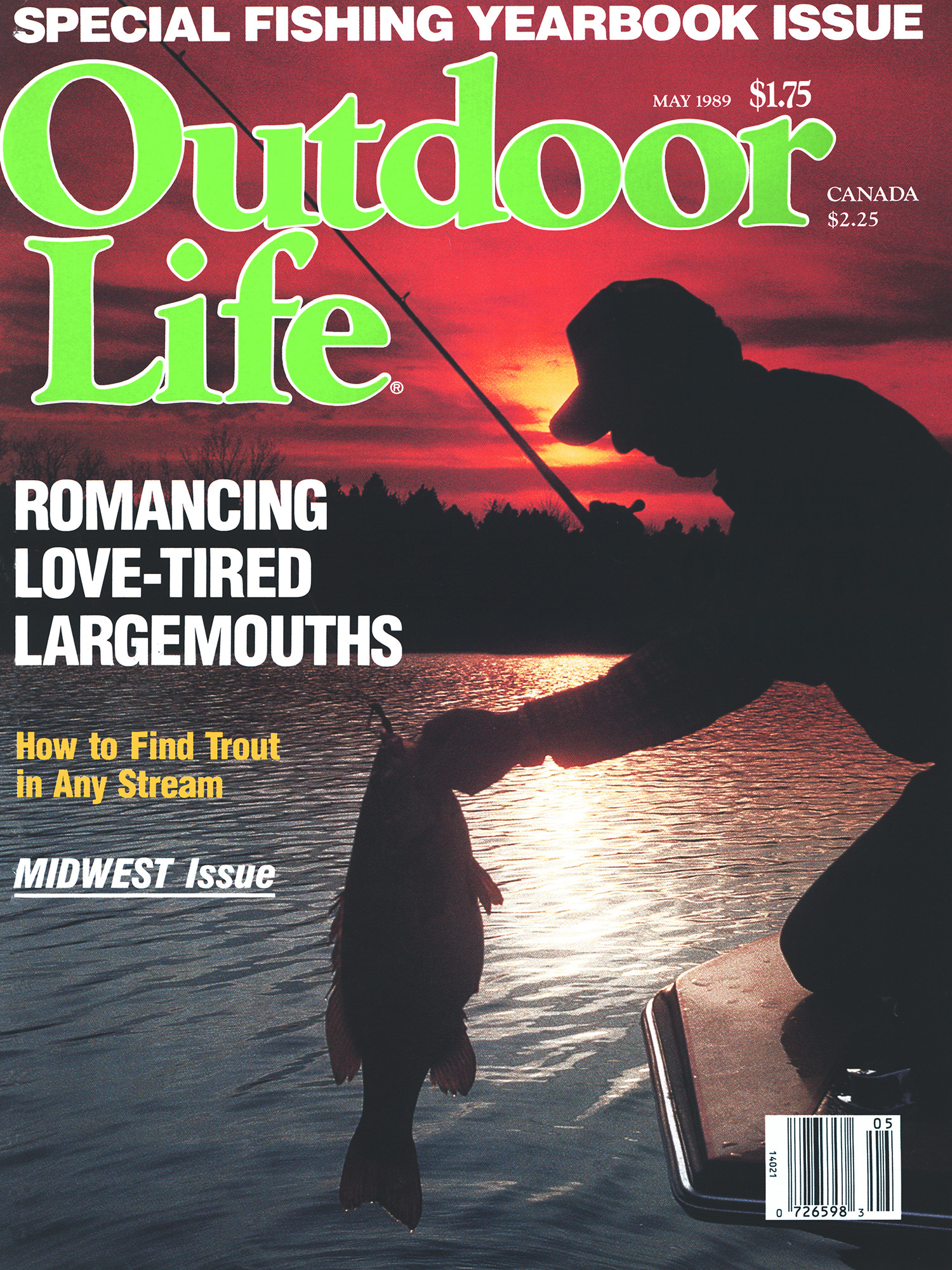

This story, “Murphy’s Pride,” originally ran in the May 1989 issue of Outdoor Life.

In the fireplace, a log burned through and set off a fusillade of sparks as it plunked between the andirons. Murphy stopped wiping the barrel of his .30/30 and stared into the unruly blaze. “Bet it won’t be this quiet around here tomorrow night,” he said. He set the rifle aside and leaned back in his chair. “Yes siree,” he continued, “those other boys’ll start rolling in about dark, and by bedtime, the bull will be so deep we’ll have to walk on the furniture to get to our bunks.”

“Yeah, and you’ll be the chief spreader,” I told him.

Murphy stood and fixed me with his most solemn gaze. “It is my duty as founder and senior member of the camp.” He walked to the wood box, selected a slab of split red oak, and dropped it into the fireplace.

Opening day of deer season was less than 36 hours away. Murphy and I had worked hard for two days, but now the place was clean and ready. There was nothing to do but settle back and enjoy the warmth of the blaze.

Murphy’s cabin just plain looked like a deer camp. It was built of hand-hewn timbers that he had scrounged from a half dozen decaying homesteads. There was a tin roof that drummed delightfully in the rain, and a long front porch that overlooked a vast hardwood bottom. Inside, the place was a cozy combination of native woods. The walls were of rough-cut cypress and the floors of finished yellow pine. Here and there a worn deer hide offered dubious protection to bare feet on chilly mornings.

But the most dominant feature in this backwoods decor was the collection of antlers. Whitetail antlers, varnished and nailed to scraps of one-inch planks, hung in every possible location. There were racks of every conceivable size and shape, and some of the dates penciled on the makeshift plaques went back nearly five decades. It was a remarkable accumulation, a sort of visual his tory of the place, and a tribute to the bounty of the land.

“Say, Murphy,” I said. “How many of these horns are yours?”

“Well now, let me see,” he said, and ran a hand through his shock of snow-white hair. “That bunch over there is mine.” He inclined his head toward five feet of wall adjacent to the fireplace. Antlers lined the space from the ceiling halfway to the floor. There were a couple of spikes and a few forkhorns, but most of the sets had six points or better. Several were real trophies, among them the big eight-pointer he had taken the previous season.

“Which of those are yours?” I asked.

“All of ‘em.”

“What? Why, there must be 20 racks on that wall!”

“Twenty-five,” he said, “and with the 10 sets back in my bedroom and the 11 pointer over the mantel at home, that makes an even 36.”

“No kidding—36 bucks, huh?”

“Yeah, well I been at this a long time. It doesn’t nearly figure out to one a year,” Murphy said. “Of course, some years I killed two, but that means lots of years I didn’t scratch.”

Still, though, I was impressed. Under Murphy’s tutelage, I had managed to take bucks in each of the last two seasons. But that ran my average to only two of five. The fact that he had taken three dozen seemed staggering. I couldn’t help but stare at the rows of antlers. Even in the feeble glow of the single bare bulb, each set gleamed rich and dark, and I knew that each trophy held the key to a hoard of golden memories.

“Tell me something, Murphy,” I said. “Out of all these bucks, which one was the best?”

Murphy looked up at the bare rafters and pursed his lips as he considered my question. “You’re gonna have to let me smoke a pipe on that one,” he said. The old man fished a flat can of Prince Albert from his shirt pocket and loaded his Kaywoodie. He fired up the briar, then walked over and stood in a wreath of smoke as he contemplated the antlers on the wall.

Several minutes passed before Murphy turned back to me. “You know, ‘best’ is a relative term,” he said. “The 11-point is for sure the biggest, but I took an eight-point 12 seasons back that gave me fits. That’s the smartest one I’ve ever come up against. Then there’s that five-point I took the year after the bad winter, when deer were so scarce. He wasn’t too big, and not overly bright, but I’ve never hunted harder for a buck.”

He crossed the room to the doorway that led back to the sleeping quarters. “To tell the truth,” he continued, “I got a kick out of every one of those deer, and I can’t rightly say which one I think is best. But—this is the rack that I’m most proud of.”

The old man reached up and rested his hand on a set of antlers nailed above the portal. The antlers had dark, flat beams, and I guessed the spread at a tad under 18 inches. Except for a broken brow tine on the right side, there would have been 10 well-matched points.

By local standards, it was a fine trophy, but I was confused. Earlier, when counting his lifetime bag, Murphy had not included that animal in the total. I opened my mouth to ask about that, but he cut me off.

“I located this big fella in September,” he said. “The equinox was two days gone, but it was still hot. Too hot to be thinking about deer hunting. But it was only six weeks until opening day, and that’s not a whit too early to scout out a prospect. Not many folks in the woods yet, you see, and the deer haven’t been spooked.”

Murphy left the doorway and moved back to his chair. Outside, the wind had picked up, and the huge loblolly at the cor ner of the porch creaked and groaned. Down in the bottom, an owl called, but the old man took no notice. He leaned his head against the back of his chair and continued his story.

“You know that big clear-cut-north of what we call ‘Dollar Creek’?”

I nodded.

“Back then, it was only about two seasons old. It was plumb choked with beggar’s lice. Deer ‘round here’ll walk a half-day for a mouthful of that stuff, so I figured that was a good place to start looking. The paper company had plowed a firebreak clean around the whole 400 acres. I decided to walk it to see if I could find a good set of tracks.

“Well, there were tracks everywhere, but it wasn’t until I got all the way around to the northeastern corner that I found what I wanted. Right there, a spring branch curved out into the clearing and formed a circular depression about 150 yards across. A hill hid this little hollow from the rest of the clearing. It looked like a nice secluded place for a careful ol’ buck to browse; and sure enough, I found some good sets of tracks right in the firebreak.

“Every afternoon for the next week, I watched that spot. Lordy, it was hot, and the mosquitoes near ‘bout took me off, but I didn’t see so much as a polecat. But each day, I found fresh tracks, so I knew that those deer were bound to be feeding late at night. My only chance to get a look at ‘em was to get up there in the morning—maybe catch ’em about daylight going back to their beds.

“So, I swapped shifts at the mill, got up real early, and drove out. The batteries in my flashlight were weak, so it was tough to find my spot in the dark. When I did find it, I came within a hair of sitting down on a big ol’ copperhead. Don’t know yet why that rascal didn’t bite me, except maybe I scared him bad as he scared me.

“Well, sir, I finally got settled in, and just as it was starting to get light, a deer walked out in the firebreak 100 yards away. I put my binoculars on him and saw that he was a fat forkhorn. While I watched, another deer eased out of the clear-cut, stopped and stared back over his shoulders. He looked like a clone of the first buck.

“Man, was I disappointed! I hadn’t burned all that gasoline, fought those mosquitoes, and nearly got snakebit for any little bitty ol’ four-point.”

Murphy paused to wrinkle his brow and shake his head at the remembrance. Then he looked at me and grinned. “But the way that second deer looked back,” he said, “I’d have bet a box of shells that there was a third one in the bunch. So, I just sat tight and kept my glasses on that spot. I musta waited 20 minutes before that rascal walked out in the open. The second I saw him, I knew I was looking at the winner of that year’s big buck pot.”

The old man’s eyes sparkled with the recollection. He stared for a moment at the antlers on the wall, then shifted his gaze to the fireplace, but I knew he saw much farther than the dancing flames. “But you know,” he said in a while, “it’s one thing to find a buck in September, and quite another to shoot him on opening day. The trick is to get close enough, often enough, to establish his habits without spooking him. Bucks don’t get that big by being careless or stupid. Crowd him the least little bit, and he’ll go completely nocturnal on you.

“I was real careful to see that didn’t happen. I washed my clothes between each scouting trip, and I always kept a masking scent on my boots. Of course, I was as quiet as possible. Whenever I moved, I went slowly, like I was stillhunting.

“Even at that, I almost lost him. Squirrel season opened, and several ol’ boys got to hunting back of that clear-cut. Guess all that shooting and carrying on was too much for him. I saw that pair of forkhorns often, but two weeks went by, and I didn’t see a sign of ol’ big boy.

“So, I doubled my scouting time, sometimes coming out both mornings and evenings. I was about ready to give up on him when I decided to check a creek bottom farther east. There were several large overcup oaks in that drainage, and there was a good crop of acorns that year.

“Well, Saturday morning I got there long before daylight. A cold drizzle was falling, and there was almost no wind. It was a perfect day for deer to move, so I backed up under a little holly where I could keep somewhat dry and still see those oaks.

“Sure enough, about 7 a.m., ol’ big boy came feeding through. Man oh man, did he look prime! His neck was swollen from the rut, and he had those horns polished nearly white. He fed pretty close to me a time or two, and I was scared to death he was gonna see me. But I was hidden good, and finally he got enough acorns and headed east, up a steep ridge that ran parallel to the creek. I waited a half-hour, then eased up the ridge.

“I was so busy daydreaming that I didn’t hear the deer coming. I just happened to look up, and there he was—big as life—as if he had materialized out of the mist. Before I could get in gear, he turned and started up the road. I raised the rifle and thumbed back the hammer.”

“At the top, the buck had intersected an old logging road. That’s where I waited on him the next morning. He came along just after daylight. Four more times I watched him. Twice he continued on across the road to bed in the branches of a huge windfallen cedar, and twice he turned north and followed the ruts of the old road about a quarter-mile to bed in the corner of what was once a hay meadow, but had become a thicket of wild blackberry and pine saplings. I built my stand in the fork of a red oak about 30 yards beyond where the buck always cut the road.”

Murphy’s dark eyes flashed with excitement. He leaned forward in his chair, and his voice grew more intense. “Come deer season, I was fit to be tied,” he said. “Talk about having something wired—I figured that not only was it a cinch to take the big buck pot, but it was a pretty fair bet I’d take first buck as well.”

Here, Murphy’s memories became nearly too much for him. He vaulted from his seat and paced before the fireplace. “Only thing that could foul me up,” he said, “was if one of the other fellows got wind of ol’ big boy. We had a pretty competitive bunch back then, and some of the guys would try to cut in on you if they thought you were working a real good buck.

“I checked around good as I could, and found out that, as usual, most of ’em were going to hunt down toward the river-in the big bottom. Bob Peters was the only one planning to head up my way. Seems he had his kid along, and because it was the boy’s first hunt, Bob wanted to put him on a stand where he would be kinda out of the way. Asked me what I thought about setting the boy up where he could watch the logging road near the corner of the old meadow.

“Well, I came close to swallowin’ my upper plate. I mean—that was getting too close for comfort. But I couldn’t say anything for fear of tipping my hand in front of the whole blamed camp. So I told him, ‘Sure, go ahead and put the boy there.’ I figured, what the hell—that buck wasn’t gonna make it that far, anyway, and the boy might come in handy when it came to dragging the big rascal back to camp.”

Then, the old man suddenly became quiet. He returned to his chair and sat for a long time, puffing his pipe and staring at the antlers that had prompted his monologue. When he spoke again, his voice was laced with a new softness, and his conver sation took a strange tack. “This all happened before I added on to the cabin,” he told me. “In those days, everyone slept in a common room, and Bob’s kid drew the bunk above mine.

“Man, you never heard anybody toss and turn like that in all your life. Every five minutes, that boy’d flip over. Then, he’d doze off only to be wakened by the vision of some ol’ big buck with a rocking-chair rack. I knew just how it was, because I was doing the same thing myself. The night before deer season, I’m worse than a kid on Christmas Eve. Hell, I’ll be like that tomorrow night, and when I don’t feel that way about it—well, I guess it’ll be time to quit.”

Murphy nodded his head for emphasis, then returned to his narrative. “Anyway,” he said, “lying there, listening to the boy, got me to remembering what it was like when I was about his age and just starting to hang around the deer camp with my dad. You know how it is when you’re a kid. Being pleased to be allowed in the company of men, but at the same time knowin’ that you’re really not one of the group.

“It’s not a matter of age. I had a cousin only a few months older than me, but he had already taken a deer. True, it was only a spike buck, but that was enough. He had met the requirements. He was a full member of the clan while I was merely a hanger-on.

“I had to endure three seasons of that feeling before a lovesick four-pointer followed a doe too close to the stone wall where I crouched with granddad’s old hammer gun. I hadn’t thought about that in years, but the whole thing came back as clear and real as if it had happened that very day.”

By now, I was completely bewildered. I couldn’t fathom what possible connection these particular recollections, pleasant as they were, had to the antlers over the doorway. Before I could ask, however, Murphy resumed his story.

“Several hours later, as I sat in my stand and waited for shooting light, it was still on my mind. You know, it was funny. For most of two months, I’d been hunting that nine-pointer. All that time, I had thought of little else except a way to ambush that rascal. But right then, when I should have been concentrating on the task as hand, I couldn’t think of anything but the way my daddy had grinned and slapped me on the back when he found me standing over that little buck.

“I was so busy daydreaming that I didn’t hear the deer coming. I just happened to look up, and there he was—big as life—as if he had materialized out of the mist. Before I could get in gear, he turned and started up the road. I raised the rifle and thumbed back the hammer. He was headed straight away from me, so I laid the bead at the base of his neck and drew it down real fine.

“Right then, as I was about to squeeze the trigger, the thought struck me. Maybe I’d had it in the back of my mind all along. Maybe all that remembering was some sort of way of talkin’ myself into it. All I know is, I lowered the gun and let that buck walk off toward that kid on the next stand.”

Murphy stood and walked to the fireplace. The blaze had all but burned out, so he took the poker and jabbed at the embers. “I still couldn’t believe what I’d done,” he said over his shoulder. “Busting my hump to take a deer, then not dropping the hammer on him. I’ll tell you some thing, though, when I saw that boy standing over that big buck, talking 90 to nothing trying to tell his daddy and me how it happened—well—I was sure proud I’d done it.”

Outside, the wind had died down, and the yellow light of an autumn moon filtered through the window. In my mind, there lingered the picture of a grinning boy holding the antlers of that first buck, the buck against which all the bucks to come would be measured, and I wondered silently if that lad realized the true value of the gift he had been given.

Read more OL+ stories.