This story first appeared in the January 1959 issue. Charlie Elliott was a legendary writer and editor for Outdoor Life. He retired as the Southern field editor in 1972, but continued to freelance for the magazine.

THE RIDGE CREST was jagged and rocky, and it pitched down the mountain at a hazardous angle for three quarters of a mile before it leveled off. I plastered myself against its rim and glanced at Louis Brown, who had clawed his way to a perch beside me.

“You can fall off this place,” I whispered, “in three directions.”

“Well—just don’t fall,” he replied, “and don’t move a pebble if you want a shot at that ram down there.”

“We’d save bullets,” I said, “by dropping a rock on him.”

“Start crawling,” Lou instructed.

I’ve done a lot of plain and fancy stalking in my time, but no approach to a game animal has ever measured up to that crawl. We couldn’t stand, or even squat on our haunches without being spotted by the sheep. And crawling down that precipitous drop on our bellies was impossible. There wasn’t any way but on our backs to negotiate that first almost-vertical, quarter mile. I inched down, with my rifle balanced between my lap and knees. Then suddenly my elbow dislodged a stone the size of an egg, but I fielded it on the first bounce.

“Good catch. That could have started a slide big enough to bury the critter,” Lou commented dryly.

We continued downward in this crawfish fashion, and half an hour and one dislocated vertebra later, we reached the last rocky outcropping that hid us from the ram. He stood in a narrow gap about 250 yards below, majestically surveying his wild domain. For the twentieth time, I studied his head through my glass. From the spread and set of his horns, we knew they were slightly less than 40 inches, but his crown was exquisitely carved—all the way to its light-brown tips. With time running out, I knew that this was the ram I wanted.

“Think you can hit him from here?” Lou asked, softly.

“If I miss after this stalk,” I said, “I’ll use the second shell on me.”

THIS WAS THE dramatic climax of my finest hunt. The time was last August, and I was here expressly for the purpose of bringing to the readers of Outdoor Life a report on the hunting possibilities in this virtually uncharted wilderness near the Arctic Circle.

For three weeks we’d scoured the massive, unnamed mountain ranges on the bleak arctic side of the Mackenzie Mountains in Canada’s Yukon Territory. We were looking for a record Dall sheep head, but hadn’t found it. For the better part of 21 days, I’d crawled on my belly along the dizzy slopes, peering into canyons so rugged and vast that I had to push back from the edge to catch my breath. I’d been 200 yards or less from 18 rams, and had even passed up two or three with horns an inch or so longer than this one I now surveyed from the perch of an eagle. I’d also turned down others with badly broomed horns, and many sheep smaller than the one below us. Still I hadn’t seen that massive head we’d traveled more than 4,000 miles to find.

My three hunting companions were business men and ranchers from California. They were also top sportsmen, and I considered it my privilege to hunt with them. We’d combed an area of several hundred square miles and had glassed hundreds of white sheep, including ewes and lambs, and we’d left behind some rugged days with mountains that stood on end and majestic valleys I’m sure no sportsman had even seen much less hunted in before.

John Harness, who’s hunted all over North America and made two trips to Africa, took the ram with the longest curl—a shapely 41-incher. Bill Boone, a veteran of hunts in Canada, Alaska, and Africa, as well as our Western states, nailed one about the size of the ram standing below us. So did Paul Sloan, whose hunts have taken him to Mexico, Canada, Africa, and many times to the Southwest. I was the only one who hadn’t scored.

We were hunting in one of the last great wilderness areas of North America. From the northernmost highway in the Yukon Territory, a gravel road running east and west between Keno Hill, Mayo Landing and Dawson—famous old town of gold-rush days—the earth reaches out in a rugged and desolate pattern for 400 miles to the rim of the Arctic Ocean. Some of the Yukon River’s headwaters rise here, then head westward across Alaska, but most of the watersheds feed their nameless creeks and rivers northward off the bleak ranges and eventually into the Mackenzie River and the Arctic Ocean.

Only a few of the mountains, rivers, and creeks have names. Some of the country was mapped a few years ago by such sketchy methods as triangulation and key points. A couple of survey teams went through on horse back, but most of the contour data was gathered by survey crews in helicopters.

For 10 days before we flew out of Dawson on a charter plane to meet him, our outfitter, Louis Brown, had made his way north from Mayo Landing with the pack string for 250 winding miles into the heart of the hunt ing territory assigned to him by the Yukon Game Department. Lou has hunted and trapped this country for 25 years—10 as a commercial outfitter—but there were tremendous chunks of his 12,000 square miles of up-ended terrain just south of the Arctic Circle where even he had never left a boot print.

Two and a half hours of flying over the endless, unpeopled ranges convinced me that we were one of the most isolated hunting parties on the continent.

We found Lou Brown waiting at an isolated lake on Wind River, where he and the plane’s pilot had agreed in advance to meet. From the moment I laid eyes on Lou, I was impressed. He’s a handsome, powerfully built Canadian in his middle 40s. Originally from Alberta, he came into the country as a young man, lured by the spell of the far northland. At Great Slave Lake, in Northwest Territories, he failed to find work, but met another adventurer building a boat to float the Mackenzie River 1,000 miles to its mouth. Lou helped him complete his boat, and together they made the two month trip to the Arctic Ocean. Lou left his companion at Ft. McPherson, came up the Peel River to the Bonnet Plume, and crossed the rugged mountain range afoot to Mayo Landing. He’s lived there ever since, except for two years he spent trapping in the Bonnet Plume country.

Many times you can judge a man by his horses. Most of the string of pack and saddle horses we had were bred and raised by our outfitter. There were no squealers, biters, or kickers in the bunch. They were mountain-wise and sure-footed in a country where one misstep on the trailless slopes might spell disaster. Lou was as gentle with his guides as he was with his horses, and I never heard him raise his voice, even in the tight places.

To do the cooking for our party, he’d brought along Vic (Frenchy) Poirier. Originally from Quebec, Frenchy spent some time in Alberta, and landed finally at Mayo where he did a stretch in the Keno mines before opening a little restaurant. He’d closed down his eating establishment to come on this hunting trip. Rugged and handsome, Frenchy knew guns, and could handle a rifle or a horse. And with the simple iron stove in the cook tent, he baked bread and turned out a brand of meals you’d expect at home.

Four men from the Loucheux tribe completed our party. They were Bob Martin, Paul Sloan’s guide; Doc Johnny, chief guide and Bill Boone’s shadow; Jimmy Davis, horse wrangler, woodcutter, and handy man around camp; and Paul Germain, assigned to me.

It took me only one afternoon to discover that he had the sharpest eyes of any man I’ve ever known. We were on a mountainside above our first Wind River camp, and he called my attention to a white dot high on a distant slope.

“Sheep,” he said.

I found the dot through my 8X binoculars.

“Just another white rock,” I replied.

The guide nodded, but kept looking. I was glassing another slope when he touched my arm and pointed to the dot again.

“Sheep.”

I swung the glasses, and sure enough, my “rock” had moved and was standing broadside so I could make out neck, legs, and body.

“Ram,” he said.

I believed him, and we climbed to get a better look at the horns. From the valley, where we tied our horses, the ram didn’t look too far away. But five hours afoot on the almost-vertical moss patches and rockslides, gave me my first appreciation of the area’s tremendous distances. I fell, winded, on my belly, and we crawled to a rim over looking a ragged canyon.

From the creek bottom we’d spotted only one; now we saw three rams grazing on the sparse grass. Two were small. The third had a fair curl on one side, but his other horn ended in a jagged break. Lou told me later that he’s seen many sheep break off their horns by jabbing the ends into rock cracks and twisting until the points snap off. Then they further broom the ragged edge by rubbing it against rough boulders. This happens, Lou figures, when the horns grow too long, the curl extending past the ram’s eye and obstructing his vision at certain angles.

The sheep were grazing away from us now, and I thought I made my guide understand that we should get close enough for pictures. We crawled over the canyon rim, pulled ourselves up the other side of the slot by handholds, and snaked along on our bellies across the rocky hillside. We paused to watch one of the rams lie down.

Since we’d run out of boulders and brush to hide behind, we stood up and walked directly toward the rams. The largest, which was lying down, scrambled to his feet, and Paul grabbed my arm.

“Shoot! He’s running!”

I continued to saunter along and the rams walked slowly in front of us until they stood on the skyline.

“Shoot!” he pleaded.

I took a picture and continued my slow advance, pausing now and then until I was about 100 feet away. The ram highest on the mountain got a little jittery and turned as if to leave.

“Baaa-a-a,” I said.

That snapped him to attention, we strolled another 10 feet closer, and I took one last picture as all three stepped beyond the crest of the mountain.

On our way back, with my knees about to break in two, I could hear my guide behind me, muttering to himself: “We saw sheep on the mountain. Climbed to the top. Only took a picture. Holy smoke!”

That wasn’t the last climb we made for sheep without burning powder. I learned the hard way that 8X glasses simply aren’t strong enough for this kind of stalking. We could see sheep on the mountain and tell they were rams, yet we had no idea whether we were looking at a world-record head. So we had to climb until we were close enough to study a head, and then either go after it or turn it down. Lou kept a 20X telescope in his saddlebag and used it every day, and Paul Sloan had brought his own 20X spotting scope, which saved him and his guide plenty of footwork. But Paul Germain and I climbed and climbed, often for six or seven hours, until we were close enough to check a head with my binoculars.

Then we hunted two days with Bill Boone and Doc Johnny. The first day, the four of us stalked three sheep through a rough canyon, and climbed a slanting break in the canyon wall, coming within 100 yards of some fair rams.

The second day, we carried the spotting scope, set it up in a rocky creek bed, and picked out a ram close under the rim of a tremendous ridge flanking the valley. We tied our horses in a willow clump, packed guns, glasses, scope, lunch, and cameras, and started the climb. The route we chose ran along the crest of a steep ridge, and after five hours we were close enough to peep through a crack in the mountain wall. Now we could see two good heads instead of just the one we’d first seen. One ram was lying down, his rump toward the cold wind blowing up the mountain. The other, 200 yards to the left, was standing, staring suspiciously in our direction.

“You want him?” Bill asked.

I told him we still had plenty of time and I’d rather do more looking for a larger trophy. While we stood whispering, the ram turned and walked uphill from the craggy point, giving us a rear view of his complete curl. That decided my hunting partner. He moved to get a better shooting position over the rock. The ram, evidently seeing the movement, broke into a trot, climbing to the right.

BY NOW HE was almost 500 yards away. Bill, using a .300 Weatherby Magnum, touched off a marvelous shot for the distance, but the 150-grain handloaded Nosler bullet struck a bit low. The sheep stumbled, then went up the slope on three legs. Bill spilled two more shots at him before the ram dodged behind a rock.

“Wish I’d missed altogether,” Bill said. “Can’t leave a winged sheep in these hills.”

We’d been without water all day, so we dropped into the gut of a canyon, where a trickle of icy liquid ran from under a rock. From that point we made a dizzy climb across the slope, over acres of shale where the footing was uncertain and a misstep would have sent us crashing into the valley. We skirted towering stone pillars which looked so shaky that a hard wind might topple them.

“Ever have earthquakes here?” I asked Doc Johnny.

“Plenty of earthquakes,” he said. For my own peace of mind, I didn’t pursue the subject further. Another hour or two of this kind of climbing put us on a sawtooth, windy backbone between two immense valleys. Work ing our way along the crest, we saw three rams before we spotted Bill’s wounded animal standing on a rim with his front foot up.

It was a roof-top descent over shale, but Doc Johnny and Bill went after him, down one of the vertical slots.

We lost sight of the hunters, but saw the ram work slowly downhill at an angle. Just as he turned across a slope, we saw him stumble. A moment later the echo of a rifle shot drifted to us. The ram fell, but even with a leg out of commission, managed to cross a steep canyon and lie down on its far rim. Through the glasses, we could tell he was watching the men, though we still hadn’t seen them. After half an hour, the ram got to its feet again, practically crawled across a slanted bench, and went out of sight over a rocky wall.

Bill and Doc Johnny stayed with him. They were at least another three quarters of an hour picking their way over a steep rockslide, finally crawling to where we’d last seen the ram. There, Bill lay on his belly, trying to get as comfortable as possible, and after a long wait, squeezed off a shot. Through the glasses, I watched him push back to his knees, and shove his hunting cap back. His guide stood up, and we knew it was all over. My hunting partner had made a successful all-out effort and retrieved his cripple. He and Doc Johnny were past midnight getting to camp.

During the next two weeks, I gradually learned to identify sheep with my naked eye. I simply picked out a pattern of white dots on a mountain, and if the pattern remained the same, I knew it was rock. If it shifted, we glassed the slope for rams. If the bunch contained some sheep about half the size of others, we knew we were looking at ewes and lambs.

I also learned that even in top sheep country, good heads come hard. To be certain you don’t pass up any records, you have to get close enough to look them all over. The tremendous distances sometimes made this a real chore. One indication of a good head is the size of the sheep. But many times, after we’d climbed to look at an especially large animal, we’d find one perfect curl and the other horn broomed to a stub.

MY GUIDE and I had a couple of days when we saw no sheep. At our third camp on Bourbon Creek (Bill Boone and Frenchy gave the stream its name), we saw two big rams on the mountain. We left camp early and climbed all day to a high peak overlooking Bonnet Plume River. We followed the crest for miles, searching out the hidden nooks on both sides. The mountain was marked with sheep tracks, and dozens of beds. Much of the sign was fresh, and though our expectations ran high all day, we didn’t see a single sheep.

That same day, John Harness and Paul Sloan, hunting a dozen miles away, stumbled onto a mineral lick with more than 30 Dalls. Paul got a fleeting shot at a ram that Lou was sure would go 43 to 45 inches, but the animal was too far away and Paul only knocked a few grains of dust into its hide. John and I rode back to the lick next day. We found 16 sheep there, with only one small ram. The big bunch had moved on.

IT SEEMED to me that with only 10 or a dozen hunters going into the 12,000 square miles each fall, every mountain would be covered with sheep. Lou said that wolves take a terrible toll when the sheep bog down in deep snow and the packs can race across the top. Other sheep are killed by temperatures of 60 and 70 below, and by snowslides. Lou has found skeletons at the base of many a slope.

We left Bourbon Creek, rode through a long, timbered flat to Bonnet Plume River, then upstream eight miles before we found a spot where the water was spread over gravel bars and was shallow enough to cross with our pack string. Twenty miles from Bourbon Creek, we made our fourth camp on a high bluff. Paul Sloan set up his spotting scope, and when John Harness and I returned from a three-day fly camp 20 miles away on Pops Creek, Paul not only had collected a good trophy, but had spotted a band of rams in one of the high valleys across the river. Lou and John made an 18-hour expedition and, near sundown, John took the best ram of our safari, the 41-incher with a wide curl.

They saw other good rams in the vicinity, and next morning Lou, Doc Johnny, and I packed a horse with grub, a tarpaulin, and our sleeping bags and crossed the Bonnet Plume again in search of a big head.

We arrived at the head of the valley in late afternoon, searched out a couple of canyons, found only one slightly better-than-average head, several small rams, and a flock of ewes and lambs. It was almost dark when we got back to our horses in a downpour. We climbed into soggy saddles and rode down the creek until darkness caught us in a clump of willows and aspen.

“This,” I stated, “is stark, raw wilderness.”

“She’s sure raw and stark tonight,” Lou answered good-naturedly through the sodden darkness.

I’ve seldom faced the prospect of a drearier night, but what I didn’t count on was the skill and ingenuity of those two men. We tied the horses, then Lou swung his ax while I dragged brush to make a clearing in the stream side willows. Doc Johnny soon located a couple of sound, dry aspen poles, chopped them into splinters, and built a roaring fire that turned raindrops to steam and warmed the air under the tarp we’d pitched.

Doc Johnny hung a slab of sheep ribs over the fire to broil and we unloaded the horses, leaving on their saddles and pack saddles to keep them warm. By the time we’d spread our sleeping bags and brewed a pot of tea, the ribs were golden brown and dripping with rich juices. I’ve never had more of a sense of well-being on any hunt than I had that night.

It rained all night, and slowed to a drizzle when we got up at dawn. While we cooked breakfast, the clouds lifted; at the head of the valley we could see the tall peaks covered with snow.

“It’s a question,” Lou said, “of whether we should keep looking for the rams in this valley, or try the next one over.”

I thought about my three hunting partners waiting in camp for me to finish hunting sheep so we could move into grizzly and caribou country up river. I thought how the snowline would move farther down the mountain each day until the whole upended world was smothered in white. Most of all I thought how, after three weeks of grueling hunting, I still didn’t have the outsize trophy I wanted. I made my decision.

“If we don’t find the rams in this valley this morning, let’s go after that largest head we saw on the mountain yesterday afternoon.”

We rode upvalley again until the rocks began to punch up through the sphagnum moss; we hobbled our horses and left them to graze on the lush grass. Our glasses showed two rams looking down on us, and not another sheep. We began the long climb up the canyon which would lead us to the head of the valley, and put us on top to stalk along the backbone of the ridge above the rams.

THAT’S WHEN I went down that quarter of a mile of rocky crest on my back, leaving bits of shirt wool and patches of skin. And now Lou and I sprawled only 250 yards above the largest sheep. For the last time I covered his crown inch by inch with my variable Bausch & Lomb sighting scope set on 8X. He was the ram I wanted. I got settled down to touch one off from my .300 Magnum, custom built for me by T. C. Kennon of Atlanta, Ga.

“He’s straight downhill,” Lou whis pered. “Better hold a little low.”

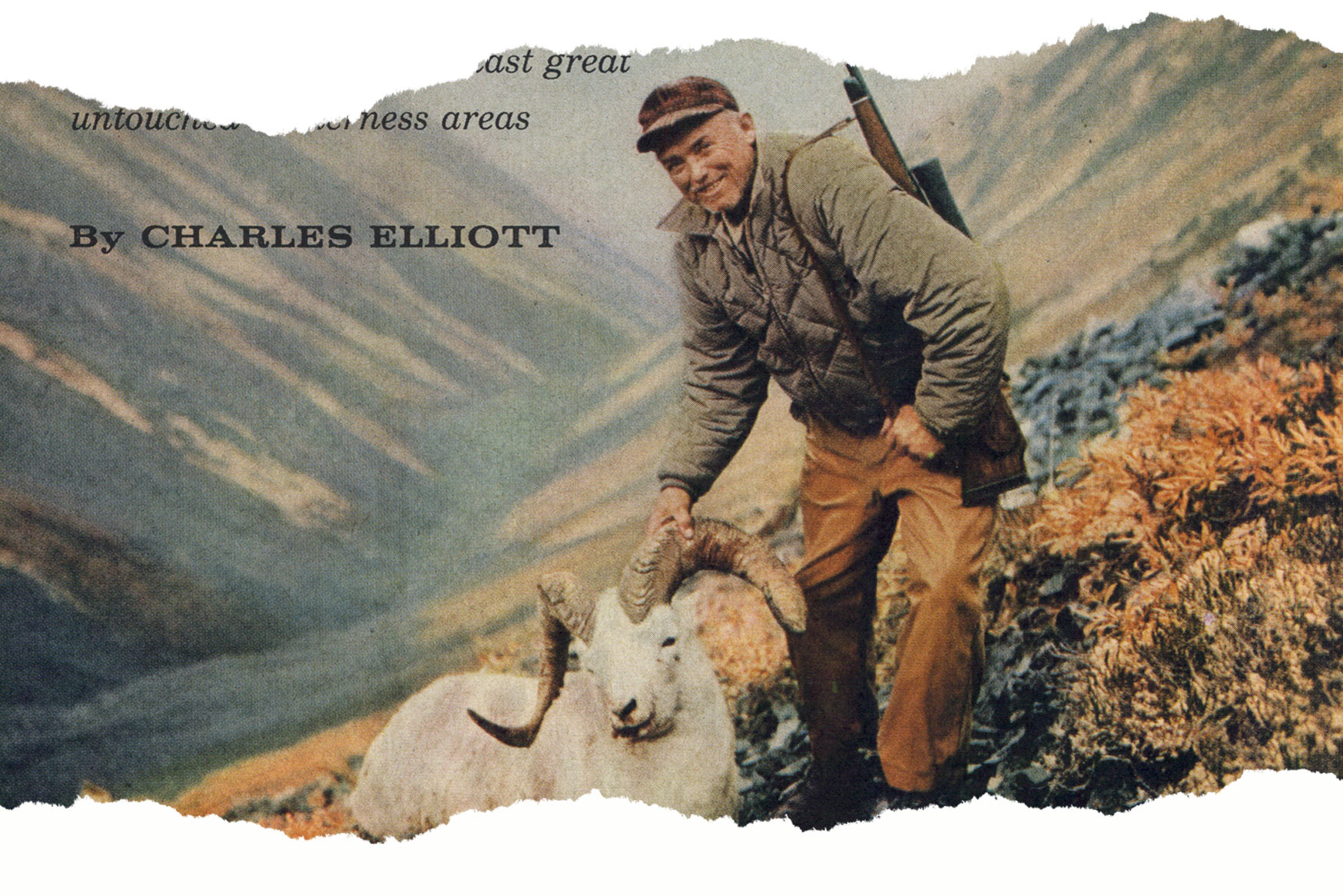

I held low and that was where my bullet hit in the chest cavity. The ram staggered and half turned, as if wondering where the standard .300 Magnum Silvertip had come from. My next shot was a little wild, hitting the ram in the rib cage and going completely through his body, only staggering him. A shoulder shot tumbled him off the sharp ridge, and he rolled almost half a mile down the treacherous slope before jamming against a rocky projection.

“Well, that’s that.” My words sounded rather abrupt, even in my own ears. Lou looked at me with his quiet, searching gaze.

“What I mean is,” I said, “that’s the end of the roughest, toughest, wildest, and finest sheep hunt I ever had.”

This text has been minimally edited to meet contemporary standards.

Read more stories from the Outdoor Life archives:

- Killer of Men: The Story of a Deadly Sloth Bear

- Boxed With a Bear: Frank Glaser’s Sled Dogs Fought a Giant Grizzly

- Arrow for a Grizzly: A Classic Fred Bear Tale