The most celebrated record in all of hunting is, without question, the world record typical whitetail buck, held by Milo Hanson. He killed the buck in November 1993, which means that if it survives this fall, it will see a 30-year anniversary.

What’s almost as remarkable as the deer itself (which scored 213 5/8) is how it has stood the test of time. In the nearly 30 years since it was killed, only one other deer has even come close to the Hanson buck. That deer was killed last year in Indiana by Dustin Huff. It scored 211 4/8.

The next biggest buck of all time is legendary James Jordan buck (206 1/8), which was killed in Wisconsin in 1914. In fact, since 1993 there have been only six typical whitetails that scored over 200 inches, according the Boone & Crockett Club record books. Meanwhile, the nontypical record has been broken several times in the last few decades.

A decade ago, Hanson predicted the next world record whitetail would come from the Midwest, likely Iowa or Wisconsin. But now several Midwestern states—Kansas, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, Kentucky, and Missouri—are known for turning out world-class bucks. Will this be the year that the Hanson Buck is topped? Just going off the numbers, probably not.

After shooting the deer, Hanson quickly became a well-traveled international superstar, accompanying the Hanson Buck to sports shows and seminars around the continent. He conducted hundreds of interviews and his photo graced the covers of numerous hunting magazines–including Outdoor Life’s.

As we head into another deer hunting season with the Hanson Buck still recognized as the world record whitetail, here’s a look back at how the record came to be. The record has lasted long enough to cover the careers of two Outdoor Life Hunting Editors, Jim Zumbo and Andrew McKean. Below you’ll find a story about how the record changed Hanson’s life, as told to McKean more than a decade ago. And the full story of Hanson’s hunt, as originally told to Zumbo. —AR

How Killing the World Record Whitetail Changed My Life

By Milo Hanson, as told to Andrew McKean (originally published in 2010)

We brought the big buck home here and hung him up out in the Quonset. Usually when we bring a deer in we’ll have a campfire out there and eat our lunch. But that day we just sat in the Quonset and looked at the deer. All of a sudden it felt like a downer. I mean, what are you going to hunt for now? Especially the other guys. They were happy for me, but how do you go back out and start hunting after that sort of deer has been taken? Anything else is, well, it’s something less.

Over the next few days people came out nonstop to look at the deer. I started getting paranoid. Maybe somebody would want to steal this deer. I started hiding it. At one point I hid his head in the barley pile. When people would come out to look at it I’d have to dig it out of the grain, and it would have all this barley in its eyes and its ears.

After the word got out, the race was on. Gordon Whittington from North American Whitetail magazine came in, then Jim Zumbo from Outdoor Life came in. It got crazy for a while, everybody bidding for the story. I didn’t know there was any value to the antlers, let alone the story.

But then I started to realize there was something to this. Our phone wouldn’t quit ringing. Most people were great, but some people tried to take advantage, thinking I didn’t know the value of this deer. People would want to trade me a half-ton (pickup) or $25,000 for it. But I wasn’t going to sell it. Why would these people want it, anyway? They didn’t shoot it.

It consumed our lives pretty well. We didn’t have an answering machine then. My son was working on the [oil] rigs at that time and he didn’t know what had happened. He could never phone home; our phone was always tied up. We had to put in an answering machine just so we could control some of these calls. At one time, my wife said, “If this doesn’t stop pretty soon, I’ll break that record with a hammer.” But overall, I’m glad it happened… There was a lot of financial benefit for us. The first six months to a year was terrible, but I had experiences to no end, things I never would have done and places I never would have gone without the buck.

For about eight years, it was non-stop. I was gone through the winters, traveling to sports shows in the States. You’d never know when the phone would ring, or somebody would stop by, trying to make a deal, own a piece of the deer. I never considered selling it. I made over $60,000 a year on it for over 10 years, and nobody ever offered me $600,000. So you do the math. I made money on appearances, and on replicas. There are about 50 replicas out there, from Cabela’s to Bass Pro to roadside museums that wanted to display the Hanson Buck.

In all my appearances, people always ask the same question: How much did it weigh? We never even weighed it, but I’d guess around 200 pounds. He wasn’t a big deer, body-wise.

READ NEXT: The Case Against Scoring Big-Game Animals

I met a lot of nice people on the road with the buck. When you get down to it, there are hunters everywhere, and they’re mainly just normal, nice people, lots of young families. You know, I held a lot of babies in the first years, and now those babies have grown up.

I think it’s genetics that made that buck, but also growing conditions. We have seen some antlers on bucks that look like him, but nothing of that size. That summer before I killed him we had 17 inches of rain, and it was a mild winter the year before. But somehow, that buck stayed hidden. They don’t get big if they can’t hide.

The next world record is going to come from the Midwest. Wisconsin wants the record back. And Iowa is coming on big-time. I think this buck is such a big deal because it’s still the record. You know James Jordan (holder of the previous record) never got any glory for his deer. He died before the record was certified.

Every fall I get nervous that the record will fall. I’m like an old buck before hunting season. I start worrying when I start hearing all the rumors. I don’t get nocturnal, but I get pretty scared of all these hunters. If I have any advice for the next record-buck holder, it’s not to rush into anything. Nowadays, it’s way easier to research things with the computer. You don’t want to rush into anything or do anything you’re not sure about. You’ll get invited everywhere but there are some places you shouldn’t go, and probably some people you shouldn’t talk to.

I’m still friends with the original crew I hunted that deer with. Did some of them think ‘it should have been me?’ There were some quiet moments after I shot him, and I’m sure some of the guys were thinking they could have had him. It was sort of sad afterward. Like I always said, it would have been cool to have catch-and-release with that buck, so we could go on hunting him forever.

The Story of the World Record Whitetail

By Milo Hanson, as told to Jim Zumbo (originally published in 1994)

It was just breaking daylight in Saskatchewan on November 23, 1993, when our hunting party met for the morning hunt. By the way my two pals were acting, I knew that something was up.

“We just at the buck,” my friend Walter Meger stammered, “but we missed. He ran into the bush, but so far we haven’t seen him come out.”

I never saw either Walter or my buddy Rene Igini so worked up of a deer in my life. Both were experienced whitetail hunters, and it took a lot to get them excited.

I immediately understood why they were carrying on that way. They had spotted the giant whitetail buck just before John Yaroshko and I drove up. I’ll admit that I was plenty excited, too. Maybe we had a chance at the monster buck after all.

I didn’t know it then, but it was to be a day that would have a permanent and profound impact on my life, one that I never dreamed possible. By noon, I would have accomplished a feat that whitetail hunters in North America have been anticipating for decades. I was totally unprepared for the incredible events that were to follow in the weeks and months ahead.

As I look back on it now, I wince when I think of how things could have turned out had I pulled the trigger on a very big buck that had been in my crosshairs the week before. I’d been hunting with my pal Walter Meger when the big whitetail broke out of heavy cover and ran along the bottom of an open slough. I flipped off the safety and found him in my scope. At one point, he stopped and presented a perfect shot. Something made me hesitate. The deer was impressive, easily scoring 160 or better and bigger than any buck I’d shot in a lifetime of hunting, but he wasn’t the one I was looking for.

Walter was standing close by and also drawing a bead on the buck, but he hesitated as well. I knew the deer would look a whole lot bigger when he topped out. Bucks always appear larger when their antlers are outlined in snow or blue sky.

“Don’t shoot, Walter,” I yelled. “That’s not the buck.” We both watched as the huge whitetail bounded up out of the slough and ran over the hill. At any other time I would have shot this enormous deer, but not now. We were looking for another buck. A very special buck.

It was November 18, 1993, the fourth day of the Saskatchewan deer season. A few months before the season, a local school bus driver said that he’d seen a giant buck in the vicinity of my farm. My neighbor also saw a monster buck in a pea field, and he was able to describe it to me in detail. From their reports, I knew that the deer was bigger than anything that had ever been in our area before—gar bigger.

I couldn’t wait for the 1993 season to begin, and neither could a bunch of other hunters who lived in the area. News about the giant buck spread quickly; it seemed like the whole town knew about it.

I’m 48 years old and live on my farm near Biggar, Saskatchewan. I raise a variety of crops, along with a herd of cattle. My wife, Olive, was raised on the farm, which I took over after we were married. I was raised on a farm farther south in Saskatchewan and began hunting whitetails when I was a teenager. My dad taught me how to hunt, and I’ve been crazy about chasing whitetails ever since.

My love of hunting grew over the years, and I traveled about our province pursuing mule deer, elk, moose, and antelope. And, of course, whitetails.

Farming is tough work with plenty of long hours, but when the crops are harvested each fall, I’m pretty much done in the fields. Except for tending my cows each day, I have time to hunt deer on my farm and neighboring land. I always look forward to the upcoming deer season. Olive also loves to hunt deer; she joins me every chance she can. Each day, our group cooks lunch over a fire, even though we aren’t very far from town or my farmhouse.

The 1993 season was special because we had the added excitement of hunting the tremendous buck. This wasn’t the first time we’d searched for a big buck that had been spotted before the season, but the stories about this particular deer were causing a big ruckus. The local coffee shop was buzzing with stories about the buck, and plenty of hunters were going to be looking for him. I hadn’t seen the deer myself, although I looked for him every day when I was working in the fields.

Pushing Bush

The rifle season opened on November 15, but bowhunting and blackpowder seasons started earlier. I was sure that the big buck would be taken before our firearms seasons opened, but he survived. Had anyone killed him, word would have spread like wildfire through our small town.

We hunt rolling country with bluffs on the sidehills and patches of thick willow and poplar surrounded by large fields. The patches run from just a few acres up to 30 or 40 acres, offering excellent cover for whitetails. We’re all intimately familiar with the terrain because we have been hunting it for years. Our hunting tactics involve a lot of glassing early in the morning and late in the afternoon. When we see a good buck, we figure a strategy and work together as a team.

During the day, we “push bush,” which is our term for putting on deer drives. Standers watch possible escape routes while drivers walk through cover pushing deer out.

Most of the farmers in the country allow hunting on their land as long as hunters ask permission. In our area, virtually all of the farms adjoining mine are accessible, with a couple of exceptions.

When the season finally opened on November 15, our party included several friends, along with my son, Brad. We searched hard for the big buck but didn’t see him. Because he doesn’t get much time off from his job working in the oil fields, Brad quickly ended his season by taking a modest four-point buck. Perhaps he should have waited.

Later that afternoon, my friend Walter made a big discovery while driving home from the day’s hunt. In the waning light he spotted the monster buck skylined on a hill. It was too late to do anything about the deer, but Walter couldn’t wait to tell me.

Later, I found out that another local hunter, Dwayne Zagoruy, had shot at and missed the buck on opening day. Dwayne had spotted the big deer in the morning while hunting alone and it had headed into a patch of bush. Instead of trying for the deer himself, he left to get some friends to put on a drive.

The drivers pushed the buck toward Dwayne. It was a difficult shot, and he missed. The buck headed into one of the few posted areas in our region and was safe for the time being.

We were full of enthusiasm the next morning, November 16. Immediately setting off for the area where Walter had spotted the buck the afternoon before, we hoped to find the deer’s track and follow it in the snow.

The plan didn’t work. The buck wasn’t a heavy animal and his tracks weren’t very big either. We followed his trail into a field of standing rye belonging to my hunting buddy Rene, but we lost the deer’s tracks in a maze of other prints. No one saw the big buck that day, but Walter Gamble, a member of our party, got a four-point buck a little bigger than Brad’s. Like Brad, Walter Gamble has a job in town that doesn’t allow him much time to hunt. His buck would make plenty of good sausage, and he was happy with it.

Walter Meger saw the giant buck again when he was driving to my farmhouse the next morning. All he saw was the buck’s rack and head a long way off. He rushed to my farm and once again we found the deer’s track, only to lose it as it mixed in with others. By now the tales of the big buck were spreading and becoming more believable because we’d actually seen him during hunting season. More hunters were showing up, and it was only a matter of time before somebody got him. My hope that I’d get the big buck started to diminish. Too many people were out there after him.

The next day—November 18—we put on a drive, and my friend Roy Polsfut and his son Albert joined us. Roy got a shot at and missed a buck that might have been the one we were after, but he wasn’t sure. They had to go home about midday, and that’s when Walter Meger and I spotted the big buck in the slough. We knew it wasn’t the giant, and it took all of the restraint I had to let the deer go. He was a very good buck.

But now it was a full five days into the season, and all of the sightings, missed shots, and general anticipation were reaching fever pitch. My friends Rene and John returned from a moose hunt up north and without much convincing joined our hunting group. That day and the next were generally unsuccessful.

“You Got Him, Milo”

By the time Sunday the 21st rolled around, some of us were happy to take advantage of a day’s rest. There is not Sunday hunting in Saskatchewan, so I took a break to catch up on chores on the farm. I didn’t hunt on Monday either because I had to go to town and run some errands. The hunters who were out that day hadn’t seen much of anything.

The next day, Tuesday, November 23, was the fateful day that I mentioned at the beginning of this story. After Walter and Rene shot at the big buck, the deer bounded into a heavy willow thicket of about 30 acres and didn’t appear to come out. While glassing, the two could see most of the escape routes and figured the buck was still in the willows.

We planned a strategy. Rene would push the bush, while the rest of us watched. We knew Rene had just as good a chance as we did; many times the drivers had the best opportunity for a shot. John would watch the northeast corner, Walter would take the northwest and I’d watch the south. The plan was for Rene to start from south of the 30-acre patch and work north, in hopes of moving the buck away from the southern end. One of my neighbors had a piece of posted property that the buck had run into when Dwayne missed him on opening day; we didn’t want the buck to make his escape in there again.

Things were looking up We had the whole day to find the buck, and the weather had finally give us the break we needed. Fresh snow covered the ground; if we saw the buck again, we’d be able to track him.

It was about 9 a.m. when we were positioned and ready to go. Rene started into the bush, hollering and whacking trees with a stick. Suddenly, the giant buck broke out in to the open to the north, in an area where John, Walter, and I could all see him. He was about a half-mile away.

We quickly moved up to where we’d last seen the buck, while Rene dogged him. Rene saw where the deer had crossed a road, and then he ran into George Kurbis, another hunter who was coming down the road. George hadn’t seen the buck; if he’d been there a minute or so earlier the deer would have run right into him.

Following the tracks, we learned that the buck was headed into Rene’s rye field where he’d lost his trail the week before. As we expected, the field was a maze of deer tracks made during the night, and we were unable to tell which one belonged to the buck.

I checked the road that bordered the area and saw that there were no fresh tracks crossing it. We couldn’t figure out where the buck might be, so we took up Walter’s suggestion to glass from some bluffs.

Suddenly, I spotted the giant buck running at least 1,000 yards away. I didn’t need my binoculars to see his antlers, even at that distance—they were absolutely enormous.

I watched the buck run onto my property and enter a thicket we call Willow Run. This is a rugged spot, where thick willows and poplars grow in dense stands among bluffs and big holes in the ground. The place is always waterlogged in the spring, so I never plow it. That chunk of land was a perfect hideout for a big buck.

I knew that it would be tough to push the buck out of that cover and, if we did, I figured he might try to cross into another patch just like it on my neighbor’s property. John and I watched an old road on the west side that cut through a possible escape route, while Walter watched the east side. Rene again dogged the tracks in the bus.

Sure enough, Rene got the buck running toward my neighbor’s patch of bush. The deer was running full out but spotted me and whirled back into the cover. John and I each fired at and missed the buck. Both shots were tough because by this time, the huge buck was really sailing through the thick trees.

We tried another drive in the next patch of bush but didn’t see the deer. Evidently, he’d kept right on going and was gone from that pocket before we started the drive.

By now my heart was really pumping, and I knew that my pals were just as excited. We had the buck on the run—we were intense, at full alert and press on as hard as we could. It was here that the knowledge of the land helped us enormously. With luck, we were soon going to write the final chapter of this series of drives.

That chapter was written during the very next drive. With Rene still dogging, the buck made a serious error. He was heading west, running toward the spot that John and I were watching.

As soon as the huge deer flashed out of the cover, it turned abruptly and ran straight away from me about 100 yards out. I picked him up in my scope and fired and saw him go down when the .308 bullet hit him.

“You got him, Milo,” John yelled. I couldn’t believe it and walked toward the buck, with my Model 88 Winchester lowered. John had lowered his gun as well.

Suddenly, the giant buck got up on his feet and bolted into the bush. I hadn’t ejected the spent shell, so I quickly chambered a live cartridge and ran up onto a bluff where I had an elevated vantage point to look down into the cover.

When I saw the buck below me, I held for his neck and knew that the 150-grain Winchester bullet had struck him solidly. Then I ran down and approached him and saw that he wasn’t done for yet. All I could see was his head, so I held for the side of it and saw the bullet put him down for good.

I looked at my watch—it was 11 a.m. My pals joined me and we dragged the buck out of the bush by his antlers. I was shaking so bad I bummed a cigarette from one of my buddies and took a few puffs on it even though I’d given up smoking three years ago.

As we admired the buck, we noticed a fresh hole in his rack. Evidently, one of my bullets had fragmented and hit the right main beam. I had no idea at that time what the consequences might have been had the antler been sheared off—or if the antler had broken as we were dragging the buck out of the woods. I also shudder to think of what might have happened if my final shot had struck an antler directly. I was aiming for the buck’s head because that’s all I could see, but I was shaking so badly my bullet had hit him in the neck. If my bullet had cracked the skull and broken the plate, I wouldn’t be telling this story. I learned afterward that Boone and Crockett Club rules do not allow a broken antler to be repaired, and a broken skull plate would void its entry into the book. In either case, my deer couldn’t have been officially scored.

Recognizing the World Record Whitetail

We loaded the buck into the truck and took him to my shop. I wanted to take some pictures, but Olive wasn’t home and I wasn’t sure how to work the camera. We got it figured out, we managed to take a few shots that afternoon. Even though all of us were experienced hunters and knew the basics of record-book scoring, we still hadn’t realized exactly how big the buck was—though we certainly knew he was exceptional. We figured he might go 190 or even 200, but we didn’t attempt to measure him. I was pretty sure I’d win the trophy for our local big-buck contest but anything more than that was, at that point, totally unexpected.

The buck remained in my shop, and people started coming over to see it. Even though Saskatchewan produces plenty of really big bucks, mine was exceptional enough to generate a lot of interest. For several days, I still had no idea what I had hanging in my shop.

I finally learned the enormity of it all when Adam Evashenko returned from a moose hunt and came to my house for dinner on November 29, almost a week after I’d shot the deer. Adam is a former measurer for our local sportsman’s club, and he was astonished when he took a look at my buck.

Adam measured the buck carefully, added up his figures, and looked at me.

“I think something’s wrong, Milo,” he said. “My measurements add up to 214 points. I’d better add up these numbers again.”

Adam rechecked and came up with the same figure. “You add them up,” Adam said to me. “This just can’t be right.”

I added the measurements and also came up with 214. I’d watched several racks being scored for local contests and knew that Adam had scored it correctly. The buck had “clean” antlers, with not questionable tines or points except for two very small points that wouldn’t have affected the score much.

“The world record is around 206, Milo,” Adam said. “Do you realize what this means?”

About the I got a little shaky in the knees, and I knew that Adam was just as overwhelmed. I poured a toast, and we pondered the huge rack of antlers that lay before us.

The next day, my neighbor Bruce Kusher, the current measurer for our local wildlife federation, also returned home from a moose hunt.

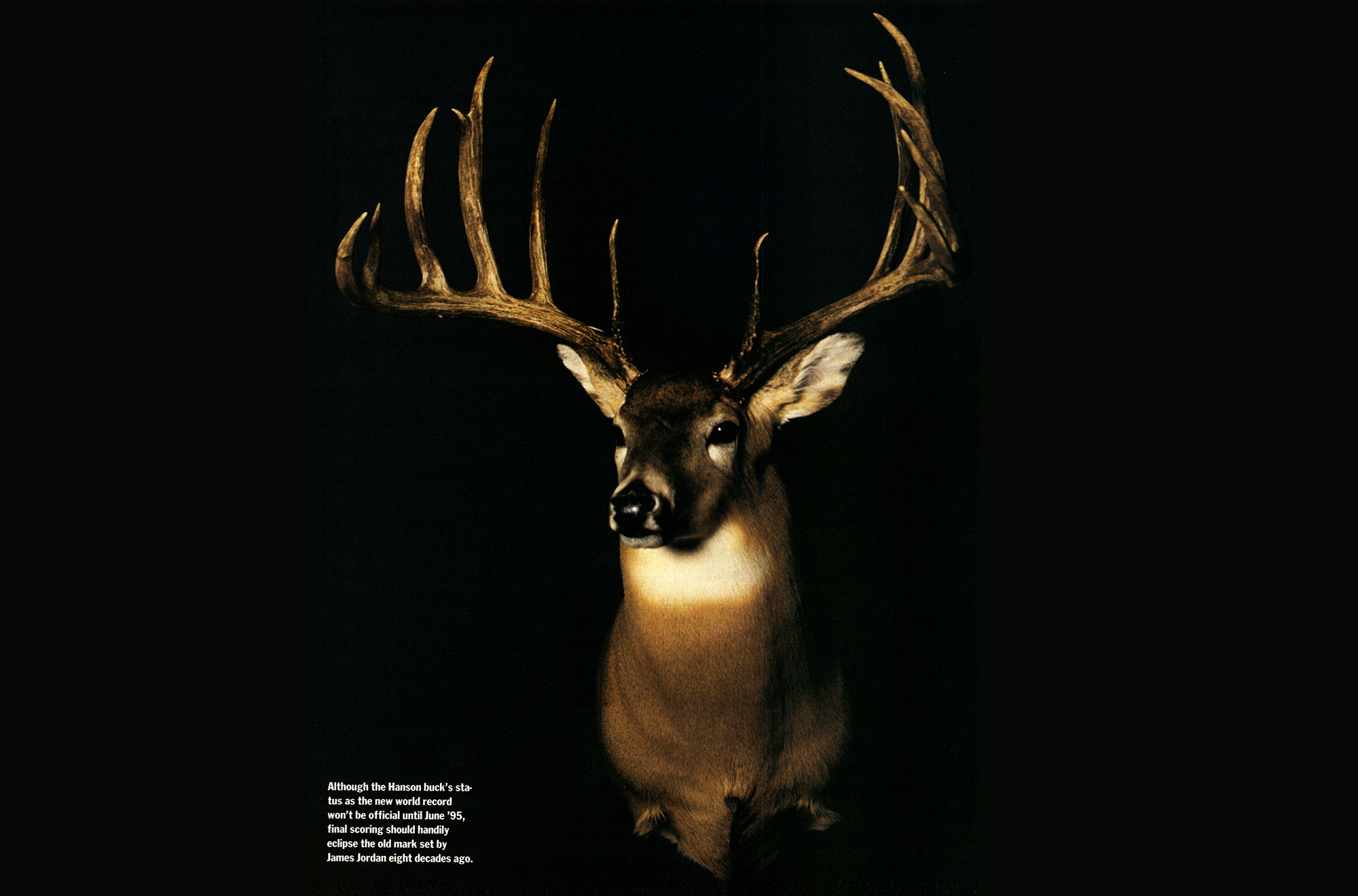

Bruce was just as amazed at the sight of the rack, and when he measured it he came up with 215 points. Like Adam, he also distrusted his figures and went through the process all over again. His final figure was 214 6/8, and he immediately checked his record book. The world-record typical whitetail, shot by Wisconsin hunter James Jordan in 1914, scored 206 1/8. My buck might beat the record that stood for eight decades!

Bruce immediately called Jim Wiebe with Saskatchewan Wildlife Federation, who didn’t believe the score. He came to my house the next evening and became a believer when he came up with a measurement of 215 5/8. His score was higher because he subtracted only one of the two small abnormal points instead of both of them.

It seemed that my buck was the new world record, a fact that I found difficult to comprehend, but the score still wasn’t official. I’d have to wait 60 days after the drying period for an official measurement.

On January 22, 1994, the buck was officially scored, measuring 213 1/8. There is yet another hurdle. A trophy that ranks that high in the book must be scored again by a panel of official measurers at the Boone and Crockett club convention to be held in Reno, Nevada, in June 1995. Boone and Crockett Club officials expect my trophy to be recognized as the number-one whitetail of all time.