When Congressman Ryan Zinke walks into Moose’s Saloon in his home district in Montana during summer recess, he looks like he just stepped off a drift boat: cargo shorts, T-shirt, river sandals, “raccoon” sunburn.

This week, news emerged that president-elect Donald Trump selected Republican Zinke to be Secretary of Interior. But how might Zinke handle that job, which oversees hundreds of millions of acres of national parks, wildlife refuges and lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management?

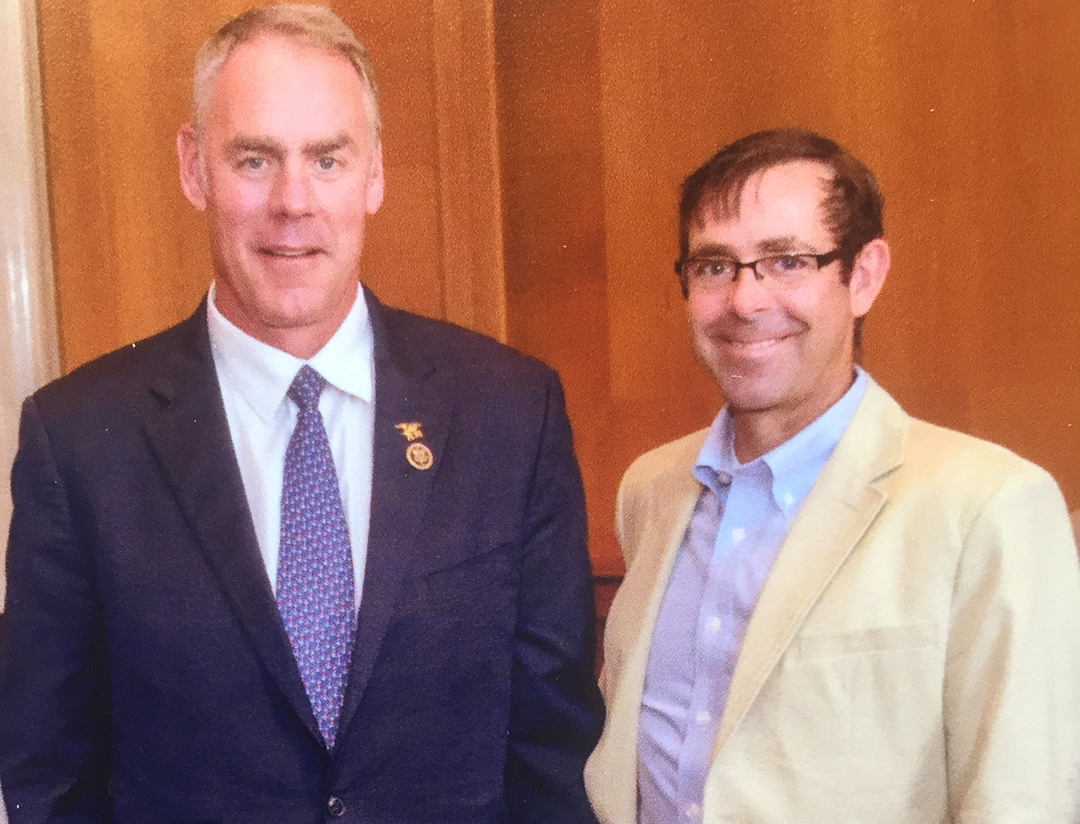

Last two times I saw Zinke at Moose’s, I thanked him for a couple of actions he took as a member of the House Natural Resource Committee. First, he bucked some Republican congressional leaders by pushing for reauthorization and funding of Land & Water Conservation Fund. Second, he again pushed back against some leaders in his Republican party that pushed for a party platform plank to dispose of public lands. Zinke responded with a quick political cliché: “I just call ‘em like I see ‘em.” But his political tradeoffs and choices are more complicated than that.

Since he first ran for office as a state legislator, Zinke has tried to brand himself as a “Theodore Roosevelt Republican” who cared about conservation at the same time he championed developing natural resources. As Secretary of the Interior, Zinke will be under the spotlight on just those issues.

Zinke was raised in Montana, hunting and fishing like just about everyone else. When he first ran for the Montana Legislature, he represented the politically purple resort community of Whitefish. He sought out—and received—endorsement of the Montana Conservation Voters, a rarity for Republicans. Once in office, he even led some committee discussions on the risk of global warming. However, that relationship soon cooled.

Zinke went on to represent Montana in Congress. His favor with the environmental community plummeted as he championed coal mining and fossil fuels. The national League of Conservation Voters gives Zinke a mere 3 percent grade for his voting record. There are several main points to Zinke’s political background that will guide his work, should he be approved to lead the Department of Interior.

Zinke is a pro-coal politician from a coal-producing state. His ties to fossil fuel industries will limit his appeal with environmental groups who prioritize climate change as their main concern. Keep an eye on how he treats sagebrush country in the West, so critical for game like pronghorn, mule deer and sage grouse.

Over decades, Zinke watched the collapse of the timber industry in Montana and has often waxed nostalgic about returning loggers to the woods.

At the same time, he grew up in sight of Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. He cannot help but sense how these conserved wild lands are enormous economic engines for local communities.

Zinke’s positions on LWCF makes perfect sense when you consider how important that law is for funding access to the outdoors. More than half of the fishing access sites in Montana, for example, were purchased at least in part with LWCF dollars, which funnels royalties from offshore drilling to habitat, recreation and access projects. America’s national forests and other public lands are critical to America’s hunting and fishing heritage, and Zinke knows that.

Press reports indicate that Trump chose Zinke to lead DOI over two other prominent Republican Congress members: Raul Labrador of Idaho and Cathy McMorris Rodgers of Washington. One thing that sets Zinke apart from those two is his position against selling the public estate. That aligns more closely with promises Trump made to sportsmen on the campaign trail.

While Zinke still has a long way to go to fill the footsteps of his idol Theodore Roosevelt, in an era when some politicians are eager to pull down TR’s public land legacy, sportsmen could do a lot worse at the Department of the Interior.