We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

The .30/30 may or may not have put more deer on the table than any other cartridge in history, but even if it hasn’t, it remains a darned effective cartridge. But you can make it even more effective if you exercise two tricks that extend its reach. The .30/30 does not have to be a 150-yard-max cartridge.

Before we outline these range-extending tricks, it might be fun to explore the history of this famous .30 caliber. It actually began as the 30 Winchester Center Fire way back in 1895. It was the first smokeless powder sporting cartridge in the U.S.A. Winchester chambered it in its new, strong, Browning-designed Model 94 lever-action rifle released just the year before in 38-55 Winchester and 32-40 Winchester. Those were still blackpowder rounds.

The 30 WCF pushed a 160-grain flat-nose 1,970 fps, 600 fps faster than the popular 38-55. Consumer interest was immediately piqued. Within a few months, Marlin began chambering the same round in its Model 1893 lever-action, but they called it the .30/30. The last number referenced the 30-grains of smokeless powder it burned. Marlin contracted with Union Metallic Cartridge Company to build the ammo. The headstamp was .30/30 UMC. In 1936 Marlin modified the M93 slightly to become the M36. They modified this to become the M336 in 1948. The Marlin had side ejection which accommodated scope mounting. The Winchester M94 didn’t switch to angle ejection until 1982.

Read Next: Our 4 Favorite Deer Hunting Guns of All Time

I suspect that shooters in the late 19th century were so familiar with the caliber/powder charge system of describing cartridges that they naturally gravitated to Marlin’s .30/30 description. By 1946 Winchester finally accepted the inevitable and started calling it the .30/30 Winchester.

The original 30 WCF load was reportedly 30-grains of smokeless pushing a 160-grain bullet. Marlin’s initial load was a 170-grain bullet. By 1896 Winchester was also selling what they called “short range” cartridges using just 6-grains of powder to push 100-grain lead bullets — clearly engineered for inexpensive small game hunting. This was a useful option for “one-gun” farm and ranch families. A variety of other bullet sizes were offered by various manufacturers over the years, everything from 55-grain varmint bullets in sabots to 180-grain jacketed soft points for the biggest elk, moose, and bears.

The .30/30 case is rimmed, as are most 19th century cases, and quite small for a .30 caliber. Diameter at the head is just .422 inches. Compare that to .470 inches for the .30-06 family of cartridges, .511 inches for the belted magnums. Length of the .30/30’s powder reservoir from base to start of neck is just 1.562 inches. This leaves a water capacity of 36.6 grains with a 150-grain bullet seated. Not much.

Modern .30/30 factory ammunition generally features 150-, 160-, and 170-grain bullets at 2,400- to 2,200 fps. Federal has a 125-grain bullet at 2,570 fps and Remington builds a light, Managed Recoil load pushing a 125-grain soft point just 2,175 fps.

While slow velocities are a big part of the reason the .30/30 is considered a 150-yard deer cartridge, the flat-nose and round-nose bullets share much of the blame. Muzzle velocity is one thing. Maintaining that velocity is another. And aerodynamically inefficient flat and round nose bullets do a lousy job of this. So, one of the ways to increase downrange energy, decrease drop and minimize wind deflection of these slow bullets is to give them sharper noses. Sounds simple enough. Until you consider the tubular magazines on the M94 and M336. While tube magazines are sleek storage spaces for harboring 5 to 9 rounds (depending on barrel/magazine length,) bullets press against primers of the rounds ahead of them. A hard, sharp bullet tip could slam like a firing pin during recoil, igniting a chain reaction. Thus, blunt .30/30 bullets.

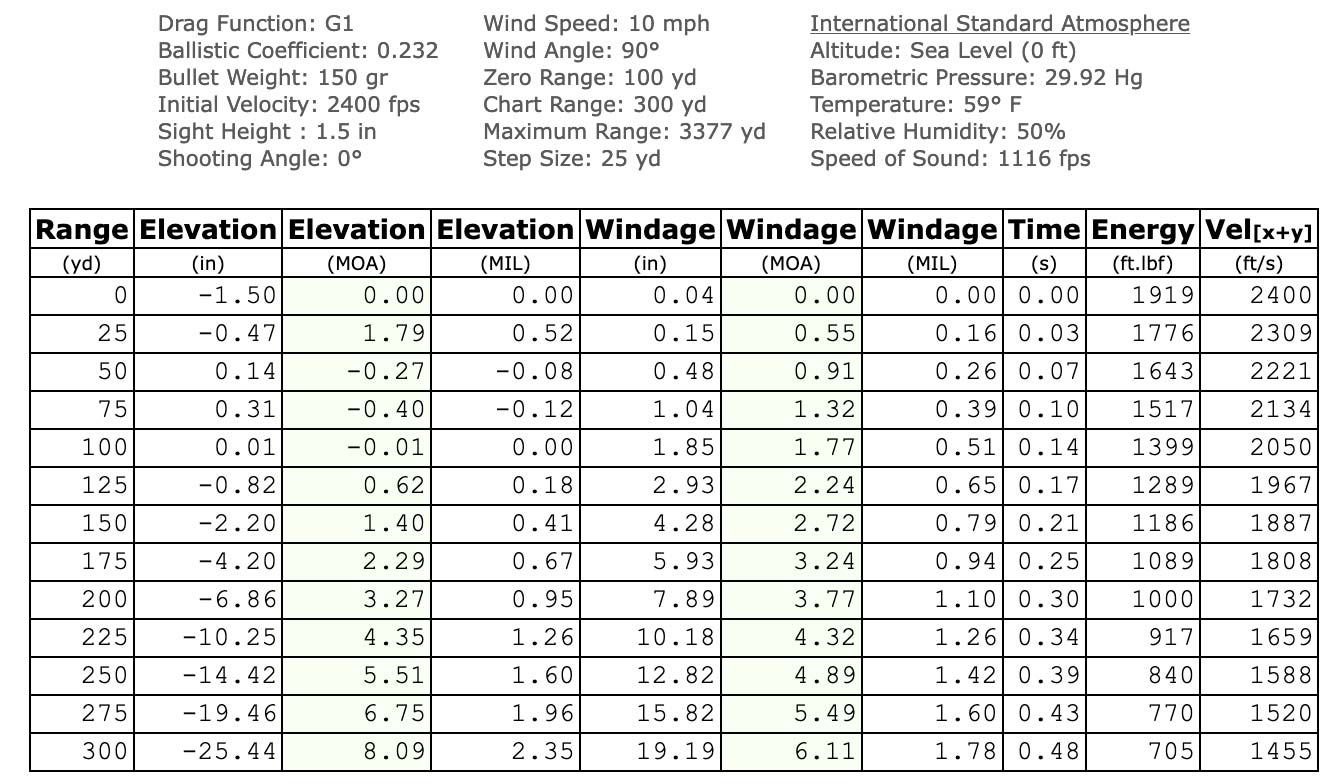

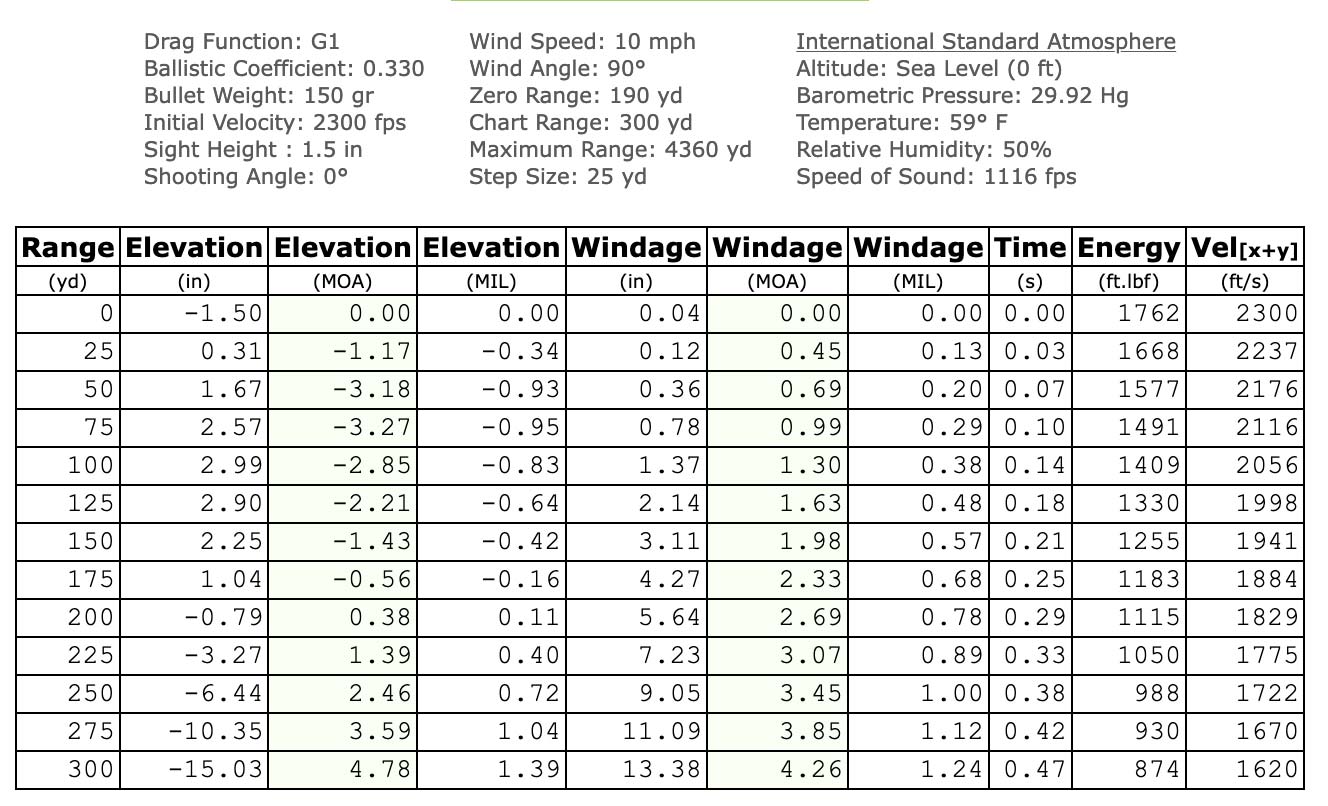

How much does a blunt bullet hurt downrange performance? Study these two trajectory tables to see. MV and zero range are the same. Only the bullet shapes, expressed as B.C., have been changed.

The higher B.C. bullet shaves a bit more than an inch off the drop at 200 yards, almost 4 inches off the wind deflection. The biggest gain is an appreciable 370 ft-lbs more energy from the spire point at 200 yards.

Alas, you’d have to shoot your .30/30 as a two-shot rifle with such sharply tipped bullets. Shove one in the magazine, chamber it, then insert one — and only one — back-up round in the magazine. Some hunters do this, but it is potentially dangerous should you or anyone else put more than one sharp-tipped load in the magazine. Fortunately, Hornady has a safer option.

Read Next: Top 10 Lever-Action Guns of All Time

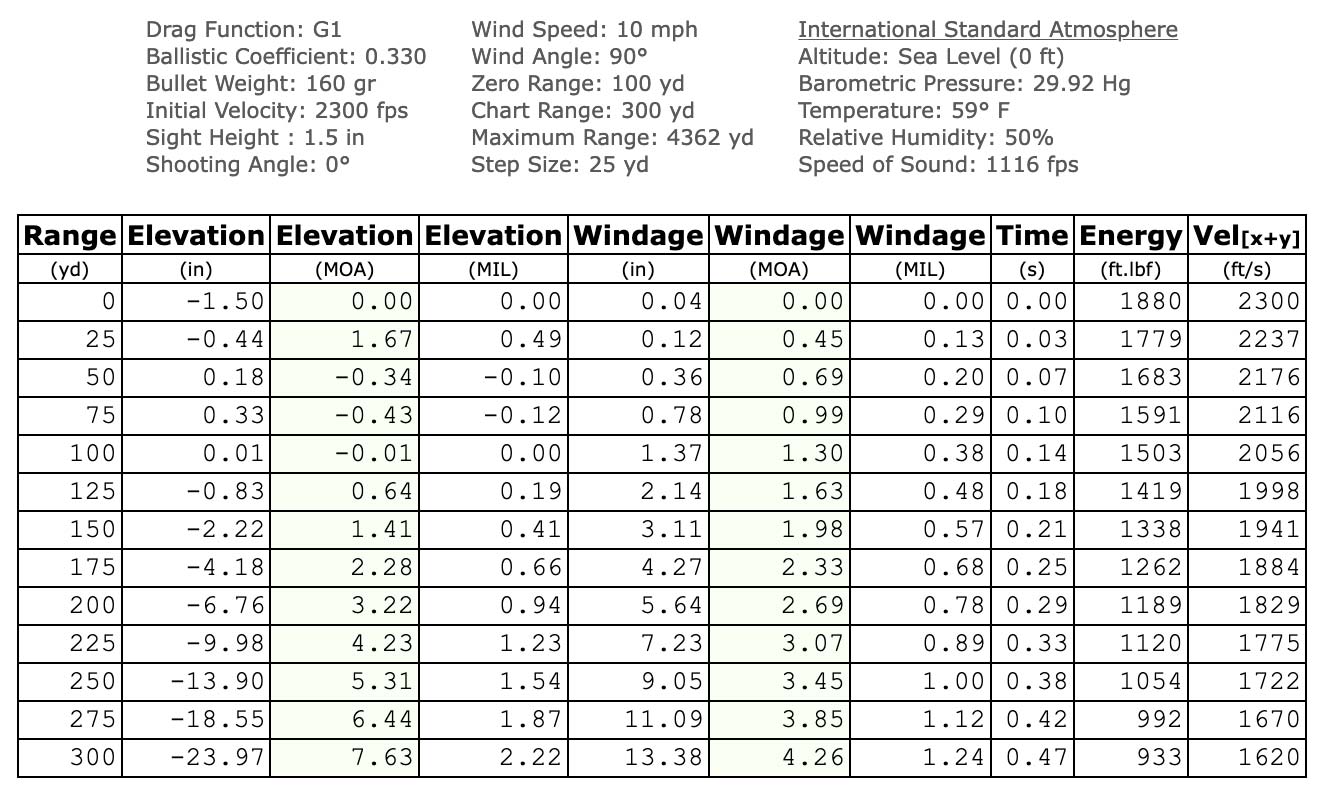

Hornady’s 140-grain MonoFlex and 160-grain FTX bullets feature pointy tips made of soft rubber. These raise B.C. slightly higher than equivalent round nose bullets. The 160-grain FTX sports the highest B.C., so let’s check trajectory of it at 2,300 fps.

The 200-yard drop gain is negligible, but the reduced wind deflection of slightly more than 2 inches is worth having. The 189 ft-lbs of additional 200-yard energy probably won’t make a huge difference, but it can’t hurt, either.

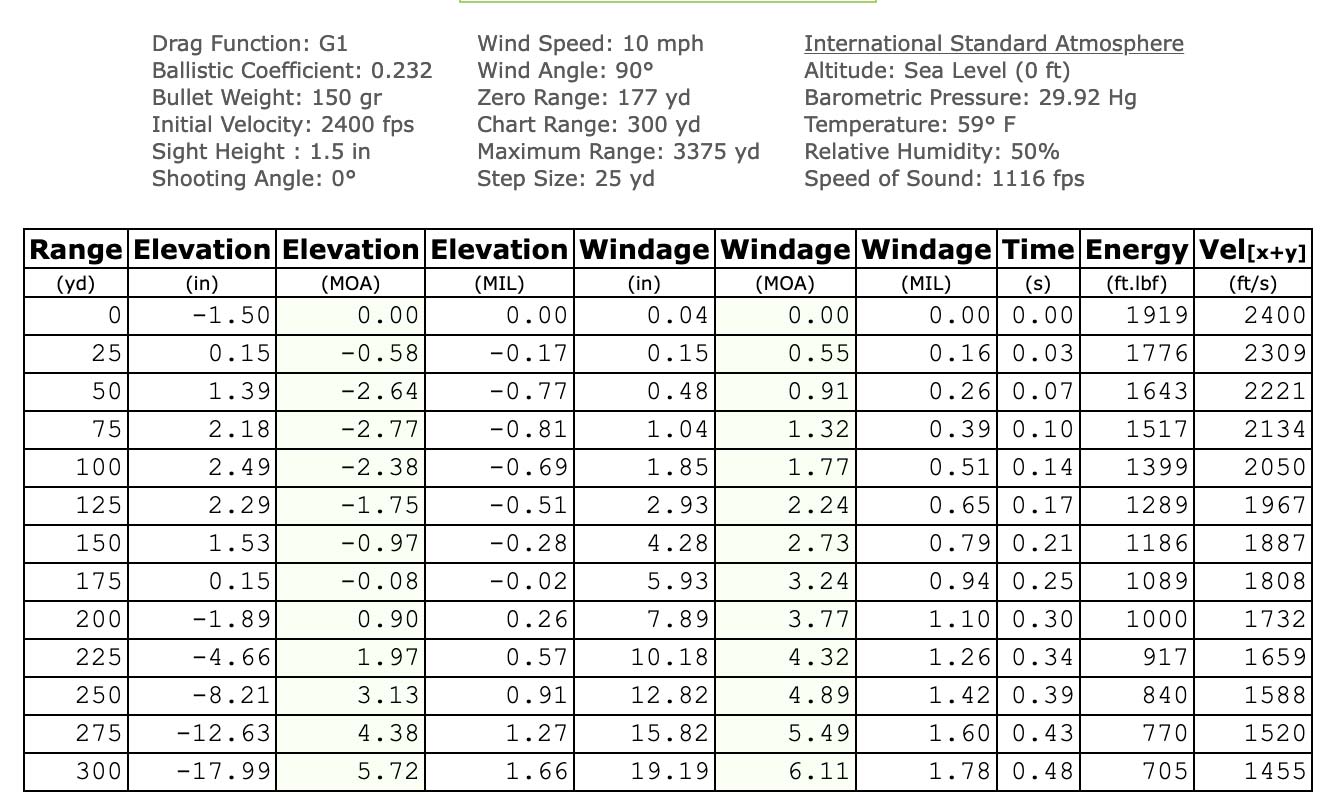

Another way to extend range of the .30/30 — regardless what bullet you choose — is to zero well beyond traditional sight-in distances. Typically, deer hunters zero their .30/30s at 50, 75, perhaps 100 yards. But what happens if we zero way out at 177 yards, the same as hitting 2.5 inches high at 100 yards? Compare this trajectory table against the 100-yard zero of the earlier trajectory table for the 150-grain Round Nose.

Check the 200-yard bullet drop in the first column. Just 1.89 inches. With the 100-yard zero, this drop was almost 7 inches. That’s a huge advantage for the 177-yard zero.

Now wait a minute! This goes against all the advice Grandpa ever gave us about the .30/30. We’re going to be hitting 2.5 inches high at 100 yards! So what? The vital zone on a whitetail’s chest is at least 10 inches top to bottom. Aim center chest and if your bullet lands 2.5 inches high, you still hit top of lungs or spine. And if you misjudge range and your buck is actually standing at 225 yards, you’ll likely hit the lower lungs or heart.

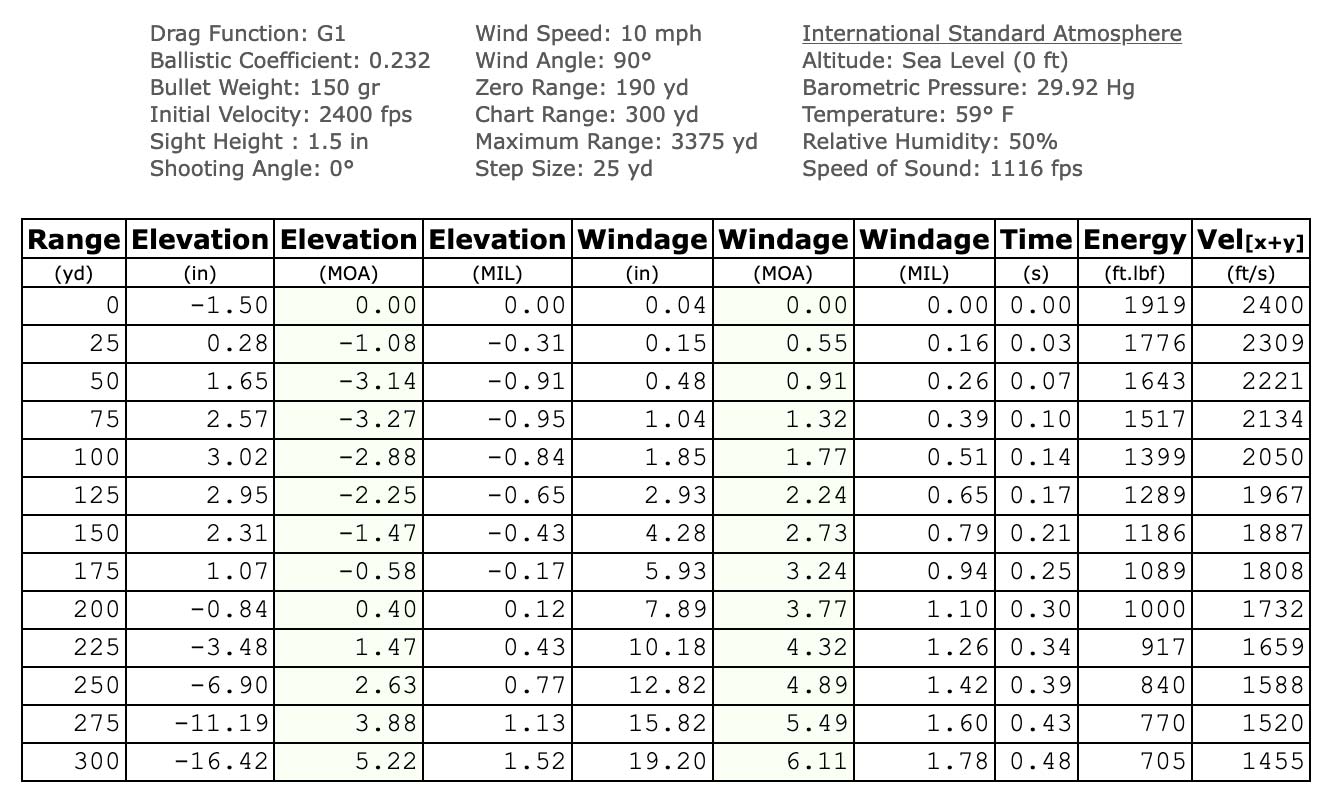

While zeroing 2.5 inches high at 100 yards might seem radical to a .30/30 shooter, it’s standard procedure for many 270 Winchester shooters. In fact, as covered in an earlier on OutdoorLife.com, Jack O’Connor regularly zeroed this way because it keeps bullets within the vital zone while compensating for misjudging range. In fact, if we want to really get brave, lets zero so our .30/30 Round Nose hits 3-inches high at 100. That puts us dead-on at a wild and crazy 190 yards.

What? A 190-yard zero for a .30/30 is about 40 yards beyond what many consider its maximum range. Great Grandpa will be rolling over in his grave. But let’s think about this. With our usual center chest hold our bullet is still going to be hitting the upper lungs, possibly the spine (assuming a calm, careful aim and trigger break.) And at every other distance it should land slightly lower until, at 225 yards, it’s falling almost 4 inches, right into the heart. I don’t know. Sounds pretty deadly and versatile to me.

Now, for our final adjustment, let’s take our higher B.C. Hornady FTX and combine it with the long-range zero.

Whoopee. We gain almost nothing in the drop column. But look at that wind deflection column. It’s an impressive 2.5-inch reduction in deflection in a 10 mph crosswind.

Finally, let’s compare both the higher B.C. Hornady FTX zeroed for 190 yards against the more traditional 150-grain Round Nose zeroed at 100 yards. Our drop advantage at 200 yards is 6 inches. Our wind advantage is 2.5 inches. Perhaps most significantly, we’ve extended our Maximum Point Blank Range from about 175 yards out to about 230 yards. That’s a huge advantage if…

If you can sight well enough to take advantage of it. If you’ve paid close attention to the details on these trajectory charts, you’ll have noted that sight height was a consistent 1.5 inches. That’s about where a scope sits above the bore. Shoot open sights with roughly a 1-inch height above bore and the trajectory curve will change slightly. More drastically, our ability to aim precisely will be compromised. I don’t know about you, but I have trouble aligning traditional, open sights on a deer beyond 100 yards in typical deer habitat. Low light, low contrast, hard to see gray hides against autumn-dull cover…

Half the fun of hunting with a M94 or M336 is their trim size and easy, flat-sided, one-hand carry. A scope, even a small one, compromises this somewhat. You might want to consider all this before going to the trouble of seeking higher B.C. bullets and zeroing them for Maximum Point Blank Range. But if you do scope your .30/30, these tricks will definitely extend its effective range.